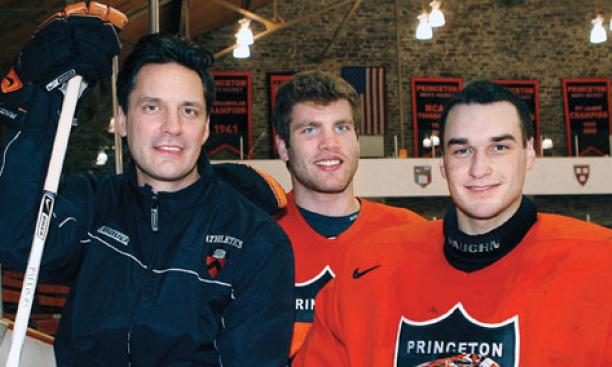

Mike Condon ’13 had not been at Princeton long before he heard the same joke numerous times: “You’re a freshman hockey player?” people would ask. “How old are you? 21?”

For the record, Condon, a goalie, is only 19, having come to Princeton directly from Belmont Hill School without playing junior hockey in Canada or the Midwest. These days, that puts him in a distinct minority. Guy Gadowsky, the Princeton men’s coach, estimates that 90 percent of the players in Division I men’s hockey have spent at least one season in a junior league; many have spent two or three. Consider the “previous schools” listed for players on this year’s Princeton roster: Of the 27 players, only five list actual schools. The others name junior hockey teams like the Fort McMurray (Alberta) Oil Barons and the Flin Flon (Manitoba) Bombers, teams situated in hockey-mad outposts of the frozen north.

In these junior hockey leagues, the players are not professionals, and if they play past age 20, they forfeit college eligibility. They live with “billet” families that the team pays to house them, and though they are in their late teens, they are treated like celebrities. Princeton forward Cam MacIntyre ’10 remembers 500 people clamoring for his autograph after games.

The practice of going for a year or two of “seasoning” is unique to hockey. It seems to have started with the hockey powers of the West in the 1980s. By the 1990s it had spread to Eastern programs eager to compete.

“What kid wouldn’t want to not go to school and to play hockey in front of 5,000 screaming fans?” says Condon, who is happy at Princeton but wonders aloud if he should have played a year of juniors since “Zane will be graduating, and there will be another spot for a goalie next year.”

Zane is star goalie Zane Kalemba ’10, who helped Princeton reach the NCAA tournament in 2008 and 2009. Kalemba spent three years at Hotchkiss before transferring to a high school in Green Bay, Wis., for his senior year. He went to class Monday through Wednesday and played for the Green Bay Gamblers the rest of the week. He wanted to apply to Princeton that year, but was urged by Gadowsky to play one more year of junior hockey.

Kalemba spent part of that second season in a suburb of Calgary and then was traded to Flin Flon, a zinc-mining town of 6,200 in northern Manitoba that is regarded as a kind of Siberia, even in the hockey community. He learned to appreciate ice fishing, moose sausage, and a warm car. He applied early decision to Princeton and got in, but he insists the extra year would have been worth it even if he hadn’t.

There are “life experience” benefits of junior hockey that Gadowsky likes to emphasize, such as time-management skills and the poise a player develops in hostile arenas. “You’re playing in a little town that gets its whole identity from the hockey team,” he says. “You’re in a fishbowl. You learn a lot of life lessons that way.”

Gadowsky notes that the players do more than just play hockey. Kalemba tutored Canadian teammates who were planning to take the SATs. MacIntyre worked part time during the season and also took correspondence courses through the University of Victoria. Gadowsky says that a player’s overall maturity helps in the classroom. Indeed, everyone in the program points with pride to Rhodes scholar (and junior-hockey alumnus) Landis Stankievech ’08.

But make no mistake: The junior system is about hockey, not academics, and not everyone is happy about the new path to playing in college. “It’s absolutely wrong,” says Bill Cleary, who coached Harvard from 1971 to 1990. “It would be different if they were taking a year of prep [school], which people used to do. But there’s no academic component with this.” Cleary argues that those who don’t want to play juniors are penalized because they must compete against the 23- and 24-year-old men who now dominate the college game.

Merrell Noden ’78 is a frequent PAW contributor.