Tenzing Sherpa ’27 is not used to taking the easy path, whether it is a physical or metaphorical one.

As an 8-year-old living in rural Nepal without internet, his life now, as an intern at Amazon Web Services, Princeton sophomore majoring in computer science, and U.S. Air Force veteran, would have seemed wildly out of reach.

And last summer, when Sherpa took a gap year to return to Nepal with other United States-based family members for a festival in his home village — Pangboche, about 10 miles from Mount Everest base camp — he quite literally had to walk off the beaten path when weather and landslides derailed their travel plans.

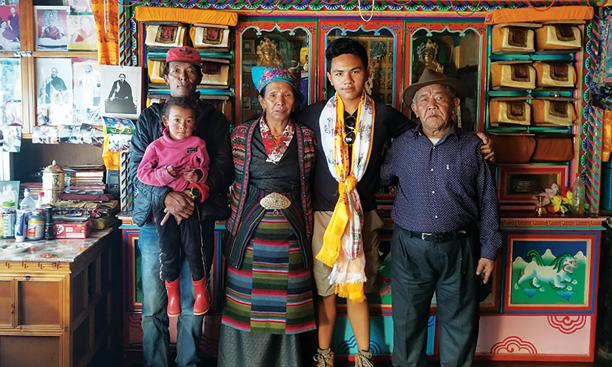

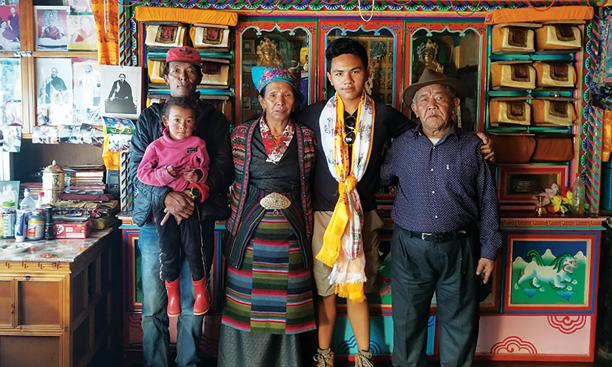

After spending a few days in Kathmandu, the country’s capital, Sherpa, along with his mother, Yangzi, and his girlfriend, Rose, spent three nail-biting days in a Jeep — “You can’t even see where the roads are, and there’s landslides everywhere. It was a mess,” he said — then hiked until they were able to hitch a ride on a passing helicopter, which took them part of the way and then dropped them off, leaving them to hike even farther to get to Pangboche, where Sherpa’s grandparents live.

Despite these obstacles on their week-long journey, Sherpa said it was more than worth it. It had been nearly two decades since his family last gathered together.

As one of just four families co-hosting the village-wide three-week Dumji festival in Pangboche, they were expected to take on extra responsibilities, ranging from daily deliveries of donations to the monastery — a 30-minute uphill trek — to making sure that everyone was well fed and having a good time. Sherpa described the event as an extended “Thanksgiving times Christmas times I don’t even know what other festivals.”

The festival honors the mythical Lama Sangwa Dorje, who established the village and was fabled to have supernatural powers such as the ability to fly. As most of the residents are illiterate, a monk read aloud from a hundreds-of-years-old pamphlet about the meaning of the festival.

“I was amazed by such a beautiful tradition that they’re still doing,” said Sherpa. According to him, the best thing about his trip to Nepal was that he “really got … back in touch with my culture.”

Sherpa was raised by his grandparents in Pangboche, but at age 9, he flew to New York City to live with his mother, who had moved to the United States when Sherpa was less than a year old. Pangboche didn’t have reliable phones at that time, and of course there was no email or Zoom either, so she essentially was a stranger.

On top of that, the two locales could not have been more different; Sherpa understandably found the move to be “quite a hard transition.”

In Nepal, he had grown up for the most part without electricity, so he “didn’t have an intuitive understanding of computers in general,” and in the States, he was struck by how much time people spent in front of the television. “At least back in the day, the TV screen looked like a big rock. … How can some people just watch this [screen] endlessly for hours?” he wondered. “I was mind blown [by] that.”

He quickly became fascinated by modern technology and learned the basics of computer science by watching videos on the internet. By the time he graduated high school, he was determined to become self-sufficient, in part to ease the burden on his single mother, who was also raising Sherpa’s younger sister, Daisy.

Though his family is devoted to Buddhism, a religion that denounces violence, Sherpa, who had become a U.S. citizen, secretly decided to join the United States Air Force.

“I saw a path for myself,” Sherpa said. “I was gonna do four years and then get out and do college.”

The choice shocked his family, but Sherpa said joining the military was the best decision for him; he was able to purchase a house in 2020 in Las Vegas (which he sold before enrolling at Princeton), and he credits his service as one of the reasons he got into Princeton. But perhaps even more importantly, his position in the military gave his mother and grandparents great pride. “They achieved some sort of the American dream through me,” he said.

After a year of training, Sherpa was stationed for three years at Camp Creech, near Las Vegas, where he worked with drones. In 2022, as his four-year commitment was coming to a close, Sherpa joined the SkillBridge program, which helps members of the military transition back into civilian life by partnering with companies that offer six-month internships to service members prior to the official conclusion of their contracts.

Sherpa landed a job with Amazon, and just weeks after that internship ended, he found out he was accepted to Princeton.

Once again, the transition was difficult for Sherpa, but he told PAW his “freshman year, I think, was really a success.” By his second semester at Princeton in the spring of 2023, he “got the groove of it,” attending office hours and participating in student clubs.

Sherpa wanted to share what he learned at Princeton back in Nepal, so during his gap year, with funding from the Class of 1978 Foundation, he taught a coding class for 20 children in a school in Kathmandu where they learned the basic foundations of computer science and about innovators like Alan Turing *38. “That’s what I really love about Princeton — there’s a lot of … glimpses of really good nuggets of information which people back in Nepal … might not know about,” he said.

While in Nepal, Sherpa also worked with his sister and grandparents to launch the Sherpa Translation Project, a platform that aims to preserve the Sherpa language, which has been classified as vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger.

The project is a work in progress, but basic words and phrases in Sherpa are currently available online at BankOfSherpa.com, sometimes accompanied by pronunciation guides voiced by Sherpa’s grandparents. He hopes to eventually add English translations and turn it into an app.

As part of his gap year, Sherpa and Rose traveled to France, Italy, and Eastern Europe, but as of July he was back in New York City working again for Amazon, as a summer intern, and preparing for his second year at Princeton.

Sherpa dreams of returning to Nepal and applying some of the high-tech skills he’s learned to support long-held traditions of the region. His grandfather, Ghalzen Sherpa, was known as an “icefall doctor” who forged dangerous paths up to Mount Everest’s peak every year. The younger Sherpa hopes to research and implement avalanche-detecting technology on the Khumbu Icefall, considered one of the most dangerous parts of Everest, to improve safety conditions for the hundreds of Nepali natives who annually shepherd climbers up the world’s tallest mountain.