On Saturday, Nov. 6, 1869, 25 Princeton students arrived in New Brunswick to participate in what generally is recognized as the first intercollegiate football game. With the ground rules set by the home team, Rutgers narrowly defeated Princeton in the legendary contest, while Princeton shut out Rutgers in a rematch at Old Nassau the following week. A third game was canceled when officials at both schools complained that “foot ball” was proving too distracting to their students.

Despite the instant popularity of this new sport, few seemed to appreciate the historical significance of college football’s first season: No official records were kept, though some players and spectators wrote detailed narratives of the action.

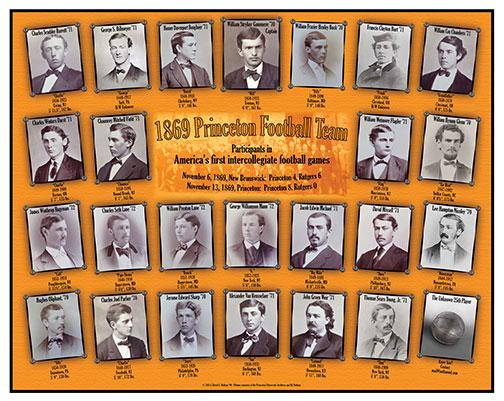

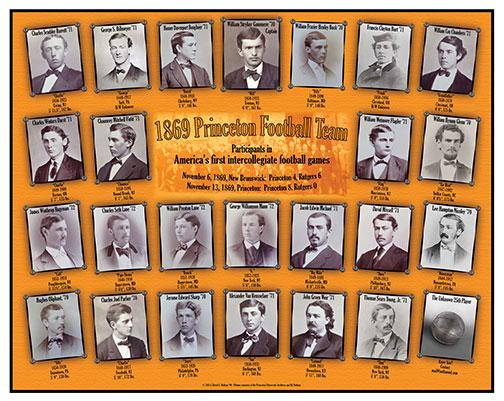

The 1869 rules put 25 men on the field for each team. History preserved the names of 27 Rutgers students who played in the 1869 season, but despite Old Nassau’s passion for history and sports, a complete roster of the Princeton team never was compiled. In the early 1900s, there were at least five attempts to reconstruct a list of all the players, yielding only 19 to 23 names.

Hoping to fill this historical void, I cross-referenced the extant lists of Princeton players and identified 24 students. I soon discovered that Steven Greene, a Rutgers alumnus and early-football researcher, had independently confirmed my findings.

The Princeton team included some interesting men: “Tar Heel” Glenn 1870 fought for the Confederacy, James Hageman 1872 threw some of baseball’s first curveballs, Alexander Van Rensselaer 1871 reached the finals in the first U.S. Open tennis tournament, and team captain Will Gummere 1870 became chief justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court.

Never-before published biographies and photographs of all known 1869 Princeton football players are posted online (click here for details).

There remains at least one teammate who has yet to be identified — Princeton’s “unknown player.” An extensive search through books, articles, school publications, and student records has come up dry.

Who could the missing man be? Looking at demographic trends among the 24 known teammates, one can narrow the list. For starters, he probably didn’t look much like a modern football player. The median height of his 1869 teammates was 5 feet, 8 inches, and the median weight a mere 162 pounds.

All identified teammates belonged to the Classes of 1870–72 (predominantly juniors), they typically were superior students, and most teammates participated in other intercollegiate sports. In fact, nearly all of the top baseball players were on the 1869 football team. So the trail of clues points toward an accomplished athlete and academically solid upperclassman of unremarkable stature.

Amateur sleuths may be able to solve this 19th-century mystery with help from modern tools. A sortable spreadsheet of data about all 327 students from the Classes of 1870–72 is also online at paw.princeton.edu/1869football, along with my list of the most promising candidates. Or perhaps the identity of the unknown player is simply tucked away in some Princetonian’s attic, written in a family memoir or alumnus’ letter home. Join the search — and share your theories — at PAW Online.