At 9:00 on a February morning, Amazon.com’s workers stream through the main portal of their corporate headquarters, the art deco shell of an old VA hospital on a ridge in southeast Seattle. Sleepy-eyed, clad in jeans and slacks, lattes in hand, these New Economy workers look like Hollywood extras for the television show Felicity or Dawson’s Creek – it’s hard to find any suited bodies or gray hair. Inside, the hospital rooms have been divided in two and furnished with desks made from wooden doors hinged together with metal plates. Like the building, it’s recycled chic. It’s also democratic – everyone, including the CEO, has the same kind of desk. The functionality of the office is a reminder of where the company began 0 in the garage of its founder’s rented Seattle home, atop desks cobbled together out of doors – and symbolic of its no-frills approach to its mission of becoming the online store that offers “Earth’s Biggest Selection” of products.

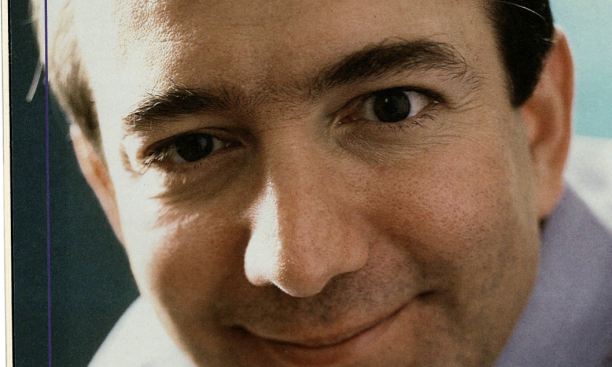

Jeff Bezos ’86, founder and CEO, arrives at his sixth-floor cubicle a bit later than most. He dedicates the start of each day to breakfast with his wide, MacKenzie Tuttle Bezos ’92, who was a creative writing major at Princeton, and their newborn son.

The grand eminence of e-commerce, who was Time magazine’s Person of the Year in 1999, is just a young guy in khakis, white shirt, no tie. His brown eyes are soft and lively, but what stands out most is his deep, honking laugh, which comes frequently. (He says his brother and sister used to refuse to sit with him at the movies because of it.) His engaging sense of humor springs from an instinctive feel for the ironies of life: for instance, he used to convene staff meetings in the café at rival bookseller Barnes and Noble because Amazon.com’s first office was too small. Honk, honk.

Bezos was, by his own admission, something of a dweeb as an electrical engineering and computer science major at Princeton. “I was a nerdy student,” he says. “I loved my studies as an engineer and got fantastic computer science education. I’d look at student businesses like the pizza delivery and part of me would think, that’s really cool. In retrospect I was overfocused on my classes, but only in retrospect.”

Of medium heigh and build, balding at age 36, Bezos seems an unlikely revolutionary. But his whirlwind enthusiasm in bringing a fanciful notion to (virtual) reality has done nothing less than revolutionize the way America – and the world – do business.

Before he cracked the cover on Amazon.com, Bezos worked for a small fund company in Manhattan, D.E. Shaw & Co. While trolling for business opportunities on the fledgling Internet, he came across data that indicated use of the new medium had grown 2,300 percent in 1993, the previous year. Anything growing at that rate, he figured, even if it were invisible today, would be ubiquitous tomorrow. He then drew up a list of businesses that he thought might profit from the Internet, looking for something that couldn’t be done in the current business model.

Books, he reasoned, could not be properly catalogued in print, because there were too many of them; but he learned from veteran booksellers that they were catalogued. They cried out to be organized in a vast, electronic database – and then sold.

The rest is e-commerce history.

When Bezos launched his bookstore on the Internet in 1995, he figured he’d sell a book a day, build the business slowly. Instead, half a million customers ordered books in the first six months. Amazon.com was a novelty: Not only was it the first bookstore in cyberspace, but it offered every title imaginable, and customers could find them in a click or two.

“We never expected such fast success,” Bezos says. “Our success made us want to invest more. Now, we want to build a store with tens of thousands of partners, where people can find anything and everything they might want to buy online. We want to build a store with standards that apply across time, country, and culture.”

More than 17 million customers in 160 countries have made Amazon.com the Web’s leading online retail site. Seventy-three percent of orders in the fourth quarter of 1999 were from repeat customers, up from 72 percent the previous quarter. Bezos has made customer focus his mantra: “We listen to the customer. We also want to innovate new services on behalf of the customer. Companies often get that wrong. They don’t develop what customers want,” he says, adding, “We want to become earth’s most customer-centric company. We will raise the bar on customer service for all companies. What Sony did for Japan – making Japan known for quality – was bigger than a company goa. It’s a mission.”

Bezos’s obsession with customer service manifested itself this past Christmas, when – after 12 frantic months of building warehouses and inventory to prepare for retail’s biggest day – an Amazon.com order place at 8:05 P.M. December 23 was fulfilled and arrived in Hawaii at 3:55 P.M. on the 24th.

Asked about risks, Bezos laughs again, honk. “How much time do I have?” he jokes.

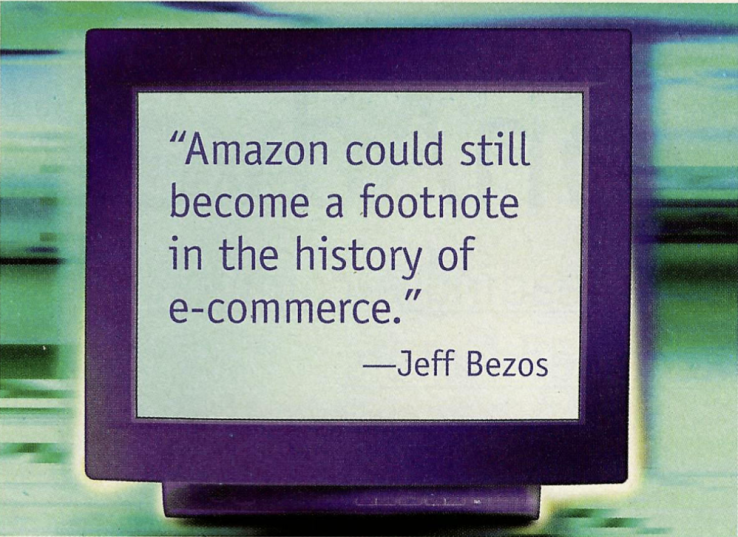

“In my opinion Amazon could still become a footnote in the history of e-commerce,” he says, more seriously. “Like all pioneers we could fail. Like Hayes, whose modems were once synonymous with quality, now gone. Failed because they lost focus, got bigger, and stopped taking risks, but [even now] we have to continue to take risks.

“Our biggest obstacle is execution risk. In the fourth quarter we grew 90 percent in three months. There’s no history that we know of where that’s happened to a company with one billion dollars plus in sales. If it sounds hard, it’s even harder to do. There’s never been a business event as time-compressed as the Internet. Compare it to the automobile and the jet – their development was spread out over 20 years. Internet compresses time. Time compression requires speed and intensity.”

Helping Bezos keep up the intensity are two other Princetonians: David Risher ’87, Amazon’s senior vice president for product development, and Jeff Wilke ’89, vice president and general manager for operations. Both come from big-company backgrounds, Risher from Microsoft and Wilke from AlliedSignal (now Honeywell).

They’ll be needed if Amazon is to keep up its breakneck pace of expansion. In the last quarter alone, Amazon opened five new “e-tail” stores. Its sale categories now include music, videos and DVDs, electronics, software, toys, video games, and home improvement, not to mention zShops, where you can buy gourmet food, among many, many other items. Amazon also partnered with Sotheby’s to create an online auction site. To round out the first quarter, Amazon added 3.8 million customer accounts, a 170 percent increase over a year earlier.

With all its growth, however, Amazon.com has yet to turn a profit, and Wall Street, which has given the company lots of leeway, has been clamoring for more attention to the bottom line. The stock has been flat this past year. Critics decry the expansion of the company away from its purer-play Internet origin, and the ever-increasing amount of resources Bezos has committed to distribution, shipping, and warehousing. “I wanted to build a small profitable company, and instead we’ve built a famously unprofitable company,” he says in response, then guffaws.

Amazon.com’s boosters point to its customer base, low customer acquisition costs, top-notch customer service, and undisputed brand name.

“It’s all about the long term,” Bezos explained to shareholders in Amazon’s 1999 annual report. “It took USA Today 11 years before it became profitable. And CNN, a long time. Both were private companies. What’s unusual for us is not that we’re investing in our company – it’s the scale and the fact that we’re a publicly held company. We will continue to invest aggressively and build the foundation for a multibillion-dollar revenue company serving tens of millions of customers with high efficiency and excellence. Our book business became profitable last quarter and will continue so in 2000. We also expect to have music and video profitable this year. We have a bunch of different companies, each at different stages of the life cycle, and some will become profitable before others.”

Amazon.com also recently formed new online partnerships with drugstore.com, a furniture store called living.com, and online audio company Audible, Inc. Internationally, Amazon has had strong success in Britain and Germany, and Bezos predicts that someday half its sales will be outside the U.S.

To thwart possible takeover attempts and to have more cash on hand for buying opportunities, the company recently asked shareholders to approve the issuance of additional common stock in the amount of $220 billion.

What does the future hold? “Next, next, and next is Amazon,” says Bezos. And a baby boy and a new house, secured by his 117.5 million shares of Amazon.com stock. He pauses, as if the future is so distant he can’t imagine. “At some point,” he continues, “assuming Amazon lasts, I’d like to do something philanthropic. I think giving away money would be as complex and challenging as running Amazon.”

This was printed in the April 19, 2000 issue of PAW.