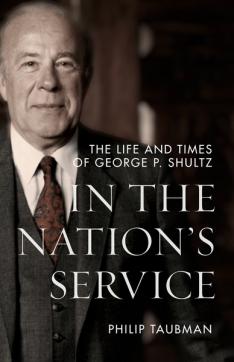

The book: The definitive biography of George Shultz ’42, In The Nation’s Service (Stanford University Press) highlights the life and legacy of this statesman. Shultz served as secretary of labor, secretary of the treasury, and secretary of state in the 1970s and 1980s, and was a pivotal player in ending the Cold War. Through personal interviews with Shultz and exclusive access to his personal papers, Philip Taubman offers a unique behind-the-scenes account of the triumphs and struggles Shultz faced throughout his career.

For more, see a Q&A with the author in PAW’s July/August Issue which can be read here.

The author: Philip Taubman is a lecturer at the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University. As a journalist specializing in national security issues, he worked as a reporter at The New York Times for about 30 years. While there he served as a Washington correspondent, Moscow bureau chief, deputy editorial page editor, Washington bureau chief, and associate editor. He also previously worked at Time and Esquire magazines.

Excerpt:

Shultz arrived at Princeton in the fall of 1938, as the world was heading toward war. In March 1938, just months before Shultz resettled at Princeton, Germany annexed Austria. During Shultz’s freshman fall, Germany also began its occupation of the Sudetenland after the appeasement of Britain, France and Italy. On November 9, 1938, Hitler unleashed Kristallnacht, the “Night of Broken Glass,” as Nazi forces ransacked thousands of Jewish homes, businesses and synagogues. As many as thirty thousand Jews were arrested and sent to concentration camps. In the Soviet Union, Stalin was strengthening his control over the Communist Party by purging party members, government officials and Red Army generals. In Asia, Imperial Japan was on the move.

At Princeton, safely ensconced amid the ivy-covered buildings, many of Shultz’s classmates harbored noninterventionist views. Their position mirrored that of much of America. With the sacrifices of the Great War still vivid for many Americans, the nation was isolationist. Mired in economic depression, Americans had little interest in engaging in another devastating international conflict when its domestic struggles were so acute. The isolationist stance persisted even as Germany and the Soviet Union signed the cynical Molotov-Ribbentrop nonaggression pact in August 1939 and as Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Britain and France declared war on Germany two days later. Although many American students wanted to provide some aid to beleaguered nations and to stem the rising tide of fascism, they continued to agitate against American military involvement.

Reportedly, six hundred Princeton students—the size of an entire undergraduate class—supported the American Independence League, an antiwar organization, within days of its formation in the fall of 1939. Princeton men were not entirely removed from the possibility of war, of course. Enrollment in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) jumped to a new high of 470 students that same fall. This corresponded to the escalation of the war in Europe. Between May and June 1940, German mechanized forces swept across Belgium, Holland and France, demonstrating the brutal efficiency of blitzkrieg warfare.

Sheltered below the elms and red oaks of Princeton, Shultz focused on his studies in economics, his major, and took courses offered by the School of Public and International Affairs. Through his affiliation with that school, he received a “real orientation to public policy,” especially in a role-playing course he took his senior year:

What they did was take a project of some kind, and one semester it would be a domestic project and the next semester it would be an international one, and you had a role... you were assigned a role. You were the secretary of the Treasury or you were the foreign minister of Japan or you were something, so you had to study and try to figure out what... if you were in that role, what would your point of view be and why, and play that out. And I found it... I thought it was just terrific. I learned a lot from it.

This interdisciplinary program provided Shultz with a taste of global affairs and government work and negotiation. At the time, though, he wasn’t “totally oriented to government,” he recalls. “Business applications of economics were also interesting.”

Between Shultz’s sophomore and junior years at Princeton, he worked as a security analyst at a New York investment advisory house headed by Benjamin Graham. Shultz was impressed by the reach of Graham’s knowledge. Here was a man who could have buried himself in numbers and details, but instead he was engaged in world events and thinking critically about their ramifications. For Shultz, immersed in his studies at Princeton, this was an impactful reminder that the outside world could not be shut out. Shultz recalled, “His book is full of the detailed way you do security analysis, but when he was looking at the investment picture, he was looking very broadly. That was a big lesson.”

Shultz appreciated the importance of finance and investment but knew early on that he did not want to throw himself into that world. Instead, he said, “I wanted to be in what I thought of as the real economy, and education was part of the real economy.” Birl Shultz, George’s father, was deeply versed in the language of Wall Street, but through an educational lens. His son wanted to integrate economics and education, applying economics to the real-life problems he observed in the midst of the Great Depression. It was a pivotal decision for the young Shultz, and it set him on an academic and career track that equipped him to operate successfully in the academic world, private sector and government service. The common element, as he realized early on, was to focus on developing practical answers to concrete problems rather than theoretical solutions to abstract challenges.

As Europe grew increasingly unsettled by Hitler’s belligerence, life at Princeton remained tranquil. During his junior and senior years, Shultz lived at “lovely 13 Blair Hall,” in Topper Cook’s words, which was Princeton’s first collegiate Gothic residence, adorned with brick chimneys and iron lantern brackets at each entry. He shared a two-bedroom suite with Topper and another friend, John Brooks, in Blair entry number one. Their Blair entry comprised mostly members of the Quadrangle eating club, whose atmosphere was less snobbish than that of some of the older Princeton clubs. Shultz and Topper joined Quadrangle at the end of their sophomore year.

Jim Baldwin considered their Quadrangle group to be fairly ordinary and down to earth: “They were a bunch of regular guys.” Quadrangle was a social group, not a political or academic one, and much of their time together was spent in fun. They ate lunch and dinner at Quadrangle and often played bridge or backgammon after eating. The group did well academically, but they “weren’t a bunch of intellectual crazies,” in Baldwin’s words. A trip to the city was a rare treat for this group. Their interactions with women were fairly limited. Princeton did not admit women until 1969, so they had to find dates at women’s colleges, such as Bryn Mawr and Vassar, or bring a woman from home to Princeton events. These barriers meant that “there weren’t many women in our lives at that time,” in Baldwin’s estimation.

Neither of the two women Shultz recalled dating at Princeton proved to be a long-term prospect. One of them was Roxy Park, a girl from Shultz’s hometown, whom he remembered bringing down to Princeton a few times. The other was Pinky Peterson. Pinky not only lived in Princeton, but she also had a car, which was quite a coup for Shultz: “At Princeton, you weren’t allowed to have a car, so now I had a girl with a car.” On winter afternoons, the two would drive over to Lake Carnegie, a reservoir at the eastern end of the campus that had been donated to the university by Andrew Carnegie, the steel magnate and philanthropist. In a scene he later described with clear affection, Pinky would lace up her figure skates and swirl around the lake, dancing gaily to music playing on the car radio that Shultz set at high volume. Standing by the car in the afternoon cold, with the door swung wide open so the radio could be heard on the lake, Shultz would happily watch her skim across the ice. “She had a great capacity to enjoy herself and to help everyone around her do the same,” he wrote to her daughter in 1996, after learning of Pinky’s death. “She was a really lovely person and I only wish I had seen more of her.”

Shultz was not a standout in either Quadrangle or his Blair entry. He was well liked, but he was not a leader among the group. He was thoughtful and hardworking, and he earned good grades, but he did not make Phi Beta Kappa as Jim Baldwin or some of his other dormmates did. Decades later, when Shultz was serving as secretary of state, his former dormmate John Brooks noted, “Maybe he’s brilliant now. He wasn’t then. He had a steady, plodding intellect.” Shultz was considered “serious but not too serious,” not an academic “grind” like some of his classmates, asserts Jim Baldwin. Simply put, he did not distinguish himself among his close friends as one destined for bigger things. He was, said Baldwin, simply “one of the guys.”

At the same time, though, his friends remember a certain consistent development on Shultz’s part during their time at Princeton. Topper Cook, who had known him since early childhood, noted that though they were academically comparable in childhood and the “pretty average kind of kids,” “the story of George Shultz is continual, continuous advancements. He got better at everything. Brighter.” Bob Young concurred, explaining that Shultz became “more and more focused.” When the group got together in the evenings, Brooks recalled that he and Topper would “say sort of halfbaked, wisecrack things, and [Shultz] would think a long time and take them very seriously.” He showed no flashes of genius but rather a steady growth, marked by a sense of integrity that, to Bob Young, “stood out even when he was in college.”

Shultz’s senior thesis—every Princeton student is required to produce one to graduate—provided an enduring lesson in the importance of learning through experience rather than just from books, theories and data. And it deeply impressed Shultz with the value of coming up with sensible solutions to challenging problems. These realizations led to a lifelong reliance on experiential learning and a proclivity to unpack complex problems dispassionately. Shultz’s thesis examined “The Agricultural Program of the Tennessee Valley Authority.” Congress and newly elected President Roosevelt had created the TVA in 1933 as a public corporation to manage the economic development of the Tennessee Valley. Shultz embarked on a summer of fieldwork to explore the TVA’s impact. Furnished with a scholarship for the summer before his senior year, he first journeyed to Washington, DC, to collect statistics before arriving in Knoxville, Tennessee, where the TVA was headquartered. He then spent two weeks living in the Tennessee mountains with what he described as a “hillbilly family,” Claud Young and his wife.

By letting them talk and helping them fill out forms for the TVA, he uncovered the immense distance between TVA headquarters in Knoxville and the realities of life in rural Tennessee, to say nothing of the remoteness of Washington. The TVA practice was to provide farmers with fertilizer. The farmers were then expected to report back on conservation practices and agricultural progress. Far from the highbrow and cerebral haunts of Princeton, Shultz saw another side to the data that he had accumulated in Knoxville and in Washington. In helping the Youngs fill out their TVA forms, Shultz realized that “the farmers knew what the government wanted to hear. They wanted to keep the fertilizer coming, and they had a kind of ethic that you don’t falsify things. On the other hand, everything is tilted, I began to see, so that they’d be sure that they got fertilizer, which they wanted. They got it free.”

He saw that “behind the numbers was a lot of plus or minus,” unrecorded and unanalyzed by the theorists behind their desks: “So I said, you know, a number is not what it looks like. And I’ve always felt that if you look at any number, your first question you have to ask is, where did it come from?” He said he grew to respect the Youngs, who “taught me a lot.” Though the couple had received “no real education,” he had observed their shrewd way of bending the TVA’s aims to their own goals and way of making a living from the land. In his thesis, dedicated to his parents and submitted in March 1942, Shultz noted that “the administering agency must recognize and respect the existing social patterns and values existing in the milieu where it plans to function” if the TVA hoped to function effectively.

Excerpted from In the Nation’s Service: The Life and Times of George P. Shultz by Philip Taubman, published by Stanford University Press, ©2023 by Philip Taubman. All Rights Reserved.

Reviews:

“Taubman makes a persuasive case that Shultz was one of the most distinguished American officials of the last half century.” — H.W. Brands, author of The Last Campaign: Sherman, Geronimo and the War for America and Reagan: The Life

“The humanity and human touch of Shultz and his biographer emerge on nearly every page.” — Walter Clemens, New York Journal of Books