Despite its small size and remoteness from the urban scene, Princeton University has hosted some unforgettable musicians. This was especially true in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s, which in retrospect were a golden age for popular music performance on campus — perhaps never to be repeated.

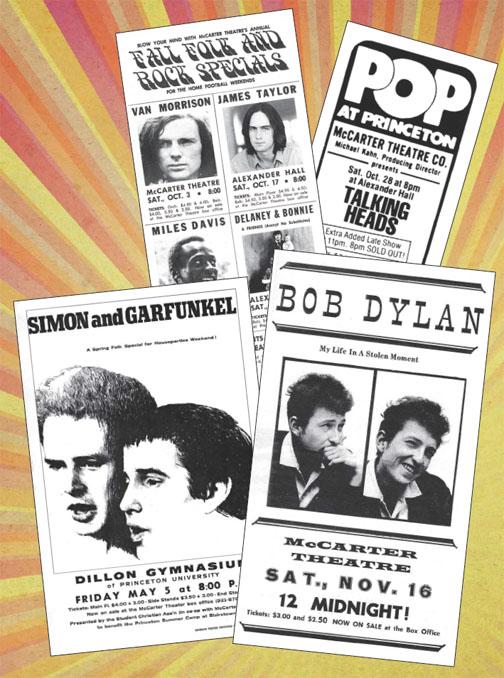

Those decades saw a renaissance that was orchestrated, to no small degree, by Bill Lockwood ’59, hired as program director and publicist at McCarter Theatre four years after graduating. Half a century later, Lockwood still works at McCarter and looks back fondly on the extraordinary musical acts he brought to town. “Those were the golden days,” he says. “McCarter had more time for concerts then. And before CDs or the Internet, live music was the place you had to go.”

Lockwood hoped to make money by signing up popular acts, whether they played at McCarter or in campus venues. He was building on a vibrant musical tradition going back to the Jazz Age, when eating clubs brought terrific artists to Prospect Avenue.

What’s your favorite concert memory? Share your story in the comments below or email paw@princeton.edu. Selections may be featured in a future issue of the magazine.

Houseparties weekends in 1929–31 featured Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, and Benny Goodman — the latter making his world debut as a band leader by playing at Cottage Club. Ella Fitzgerald sang at the Prince-Tiger Dance amid the bleachers of the gymnasium in 1936; Count Basie and Billie Holiday appeared there a year later.

Jazz remained popular at Princeton well into the rock era. Basie and Dave Brubeck were regulars; Ellington played McCarter in 1966; and four years later, Miles Davis grooved at Alexander Hall, sporting an orange leather jacket and going two hours without a break.

Even as an industrious undergraduate who organized concerts from his dormitory room, Lockwood (with classmate Tom Sternberg) had hired out McCarter for concerts by Pete Seeger and the Weavers. A few years later, working for McCarter officially, he tapped more fully into the growing craze for folk music. In 1963 he organized a Saturday midnight concert by a college dropout who played clubs in Greenwich Village, a talented 22-year-old then gaining attention for songs such as “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” and “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Tickets to Bob Dylan were $3, chargeable to your U-Store account.

“We had people seated on the stage behind him; it was just him and his guitar,” Lockwood remembers of that legendary night. “He had dark glasses on.”

As folk and folk-rock grew increasingly popular, legends played Princeton, including Arlo Guthrie (“Alice’s Restaurant”) and teenage Joan Baez, who visited the little theater at Murray-Dodge Hall in 1960. Mike Parish ’65 saw her at McCarter two years later, a “small, slender person emitting such delicate, angelic sounds. It bound the performer with the audience in a way I’ve only seen once or twice since over the last 50 years.”

Judy Collins came to Alexander Hall in 1968, in a red velvet gown, strumming two guitars and avoiding political pontificating. Collins had played Princeton before: On a single weekend on Prospect Avenue in March 1964, one could have heard Collins at Tower, bluesman John Lee Hooker at Colonial Club, and the Drifters (“Under the Boardwalk”) at Cottage.

“I had the honor of seeing Jerry Lee Lewis perform from 10 feet away in Cloister’s basement,” says Bruce Price ’63. “He performed standing and banged one heel on the keys. Most thrilling, he played heavy with the left while sweeping a comb delicately back through his killer pompadour.” Selden Edwards ’63 rocked to Chuck Berry at Tower Club. “Somehow, I got in and stood so close to him as he was playing that when he changed chords, his elbow brushed my leg. I could smell his pomade.”

James Taylor opened his show in Dillon in 1970 by quipping that he had hoped to avoid college by becoming a singer. Near the end the audience was astonished to see folk musician Joni Mitchell join him on stage. The crowd sang “Happy Birthday” to her — she had just turned 27.

Rick Shea ’73 remembers a technical glitch that night: “Suddenly a loud crackle and the PA system went silent. A murmur rippled through the crowd, but Taylor just kept picking those familiar chords until the multitude became completely quiet. Then he began singing; no amplification, just an acoustic guitar.” Voices joined in until most in the audience — estimated to be 4,000 by the Prince — gently were singing along, “Rock-a-bye sweet baby James.”

Some of the best rock concerts were at McCarter, where, in one week in 1971, you could have heard singer and actor Kris Kristofferson (“Me and Bobby McGee”) — briefly joined on stage by Carly Simon — as well as Pink Floyd, earsplitting with its six-ton portable sound system. A year later, the English band Yes played there, quickly followed by the J. Geils Band, for which a novice was paid $500 as an opening act: Billy Joel, who played “Captain Jack” and “Piano Man.”

Lockwood made use of three campus venues: Alexander Hall, which seated 1,000; Dillon Gym, 3,200; and eventually Jadwin Gym, 8,000. Long known for violin concertos and drowsy Econ 101 lectures, the Victorian-era auditorium inside Alexander Hall seemed an unlikely home for rock legends. But now it saw thunderous performances, including Lynyrd Skynyrd as an opening act in 1973 when their song “Free Bird” had just begun propelling them to fame.

Allen Furbeck ’76 saw Hot Tuna there — “probably the loudest show I ever went to. My ears rang for three days.” Marc Fisher ’80 found the Ramones disappointing: “The band played all of 15 songs for about 35 minutes. The audience was stunned that the show ended so abruptly.”

In 1971, swaths of empty seats in Alexander Hall greeted a bearded Londoner who called himself Cat Stevens. Two years later, Bette Midler appeared in Alexander Hall, and students paid $2.50 to see a progressive band from England named Genesis, starring Peter Gabriel and Phil Collins. A singer then known mostly in New Jersey, Bruce Springsteen, played two three-hour sets at Alexander Hall in 1974, a year before he hit the cover of Time magazine as “Rock’s New Sensation.”

Dillon Gym proved an imperfect setting for rock concerts, with its low ceiling, poor lighting, and seats scattered across the basketball court. But it hosted legendary acts in the Age of Aquarius, including the Lovin’ Spoonful, Simon & Garfunkel, Steppenwolf, Frank Zappa, Average White Band, and Jackson Browne. Ned Nalle ’76 saw the Beach Boys: “I remember the music amped up way too loud and classmates stuffing paper-towel bits in their ears as they danced.”

Doug Quine ’73 had an unforgettable encounter as he hitched a ride down-campus from a limousine passing Dillon Gym: “It was the Byrds!” Quine struggled to think of small talk — “What does one say? I asked how they transported their instruments from California. One of them sang a couple of lines: ‘I came from California with a guitar on my knee’ — the shortest Byrds concert in history, for a fortunate audience of one!”

The Grateful Dead’s invasion of Dillon on April 17, 1971 — Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang in tow — is famous among devotees for a quintessential performance of “Good Lovin’ ” by band member Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, then suffering from what would be fatal cirrhosis. “The concert was expensive, $10,000,” says Lockwood, a faithful Deadhead who treasures a cassette recording he made that night.

The band played until “well past midnight,” Lockwood recalls, and “a substantial part of the audience, which was all students, was stoned out of their minds.” Concertgoers passed marijuana joints down the rows of seats, he says. According to legend, when a Princeton proctor demanded that shaggy singer Jerry Garcia extinguish his joint, Garcia snarled, “I’ll never play here again.” He never did.

The construction of mammoth Jadwin Gym promised to open a new phase in popular music at Princeton, drawing ever-bigger acts that demanded a capacious venue. Jadwin would host Emerson, Lake and Palmer, the Doobie Brothers, and other chart-topping performers, though the gym never made an ideal music venue. The huge steel beams under the floor vibrated alarmingly as the crowd stamped its feet in rhythm to the Beach Boys in 1974, and some say the parquet undulated like ocean swells during a show by Springsteen in November 1978.

That school year proved a high-water mark as a series of now-fabled acts played campus. Within just five days, students danced in the aisles of Alexander Hall to David Byrne’s Talking Heads and then crowded Jadwin for the three-hour concert by Springsteen — many sporting “Bruce at the Cage” T-shirts.

Barely older than his audience, the 29-year-old “Boss” had grown up 25 miles east of campus in Freehold, N.J., and already was legendary for passionate live performances. “His solos attack the crowd, snarling and stinging,” The Daily Princetonian reported after the concert. “When he moans in seeming anguish at the end of ‘Backstreets,’ each member of the audience can feel the sympathetic pain. Or when he raises his fist in defiance during the chorus of ‘Promised Land,’ hundreds in the crowd raise their fists, too.”

More than three decades later, alumni are still talking about that Springsteen show. David Remnick ’81 remembers, “Springsteen was at his absolute feral peak as a performer, on the ascent and burning from within.” Douglas Rubin ’81 and friends were up close: “We were literally in the middle of Bruce and [saxophonist] Clarence Clemons’ ‘She’s the One’ face-off, and Bruce’s ‘Spirit in the Night’ crowd-surf jump passed over our heads into the third row. Besides holding my wife as she delivered our son, nothing else could ever compare.”

Arnold Breitbart ’81 was even closer to the Boss. “He launched into the audience, falling onto my lap. Thirty-four years later, I’m still an ardent Springsteen fan — my wife and kids would say ‘fanatic’ — having seen him on every tour since, multiple times.”

An undergrad reporter evaded security at 2:15 a.m. to accost the perspiring rock star in his basement dressing room, which usually served as the office of the tennis coach. The Boss marveled at how the students had waved their chairs in the air as the concert ended: “I’ve never seen anything like that, have you?”

But those chairs caused a big problem. The morning after the concert, Lockwood was summoned to Jadwin, where University officials were glowering. Students had stood on the metal folding chairs for much of the concert, grinding the tips of the legs into the basketball court and leaving thousands of circular scars. The repair bill was $15,000.

Since that moment, concerts have been few in Jadwin Gym.

It’s become a truism that the demise of Jadwin as a concert hall brought Princeton’s golden age of pop music to a close. But Lockwood points out that it was ending, anyway. With a busy slate of cultural offerings, McCarter Theatre had less and less time for scheduling rock ’n’ roll spectacles. Bands demanded arenas larger than Jadwin and charged ever-more-exorbitant prices, which undergraduate student governments of the 1980s struggled to meet. When Chaka Khan, the Kinks, and 10,000 Maniacs came to campus, budgets were busted.

Recent years have brought fine musical acts, including Sheryl Crow performing in Blair courtyard for the University’s 250th anniversary and a graying Dylan at Dillon in 2000. But for many alumni, the great era coincided with the heyday of folk and rock and now belongs to history.

To have heard Joan Baez sing “House of the Rising Sun” in the intimate setting of Murray-Dodge ... or Cat Stevens play “Wild World” at Alexander Hall ... or Simon & Garfunkel break into “Scarborough Fair” at Dillon Gym ... these were remarkable moments for the lucky few who were there. The rest of us can only envy them.

W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 spent three years writing Princeton: America’s Campus (2012), the first architectural history of the University.