Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

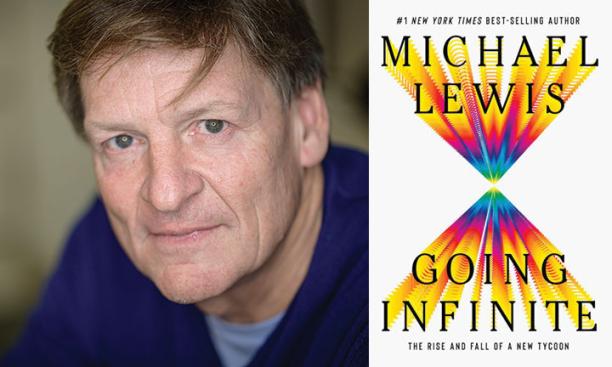

PAW’s Book Club returns with author Michael Lewis, Class of ’82, answering alumni questions about Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon, his recent book about Sam Bankman-Fried, a deeply peculiar financial mogul who very quickly built a cryptocurrency empire only to have it implode far faster just a few years later.

When we spoke with Lewis earlier this week, Bankman-Fried was awaiting sentencing for fraud and money laundering, of which he was found guilty back in the fall. (He received a 25-year prison sentence on March 28.) But in 2021, when Lewis first met him, he was a massive star in the unregulated new wild west of cryptocurrency and he had big plans to use billions of dollars to change the world. Lewis was granted remarkable access to FTX, Alameda Research, and Sam himself, and when, as they say, the stuff hit the fan, he was right in the thick of it, watching.

PAW Book Club is proud to be sponsored by the Princeton University Store. Missed this read? Join us for the next one, Bianca Bosker ’08’s work of gonzo journalism, Get the Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey Among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See. Sign up online here.

TRANSCRIPTION

Liz Daugherty: I’m Liz Daugherty and this is the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s Book Club podcast. We just finished reading Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon, and with me today is author Michael Lewis, Princeton Class of 1982. His book centers on Sam Bankman-Fried, a deeply peculiar financial mogul who very quickly built a cryptocurrency empire only to have it implode far faster just a few years later.

Today, Bankman-Fried is awaiting sentencing, in just a few days actually, for fraud and money laundering of which he was found guilty back in the fall. But in 2021, when Lewis first met him, he was a massive star in the unregulated new wild west of cryptocurrency and he had big plans to use billions of dollars to change the world. Lewis was granted remarkable access to FTX, Alameda Research, and Sam himself, and when, as they say, the stuff hit the fan, he was right in the thick of it, watching.

So Michael, thank you so much for talking with us. I have some questions here from our wonderful book club members as well as a few from the PAW staff.

Michael Lewis ’82: Let’s do it.

LD: So Susan Rhoades *92 asks, “Do you see the fall of FTX as a failure of crypto or of Sam and his team’s business organization and acumen?”

ML: It’s a very good question. I have a feeling these are going to be the best questions I’ve had on my book tour, but it’s both. Principally the latter in that the way they ran that place was insane. If your book club has the hardback, you can pull off the jacket and see the only organization chart that existed that was created by the corporate psychiatrist, because he couldn’t understand the place without it. But Sam kind of refused to have one. The shrink just created one, and just looking at that, you’ll see how insane it was.

But it wasn’t necessary that it had to fall apart for fraudulent reasons. It is not inherent in crypto that whatever you’re doing is going to be squirrelly and illegal and get you in trouble. It just seems to happen all the time. In this case, it happened a little differently than it has happened in other cases. And the fact that right from the beginning when Sam created this crypto exchange — which unlike a stock exchange, it housed the customer’s money, right? They held the customer’s money. The fact that because it was a crypto exchange, no bank would give them bank accounts. So if you, the customer who wanted to wire their dollars into this place, you couldn’t wire to FTX. The only people that had bank accounts was Sam’s private hedge fund, Alameda. So your dollars were sitting in his private hedge fund rather than FTX.

I mean, that’s both crazy from a management point of view, you’re sort of building a business where right from the beginning, the funds are commingled and in the wrong place. But it’s also pretty naturally a result of crypto. It’s because it was a crypto exchange that they couldn’t get a bank account. And if somehow crypto was more legitimized in the minds of bankers, if they weren’t afraid of having exposure to the kind of people who traded crypto, none of this might’ve happened. They might’ve had proper bank accounts right from the beginning and a segregation of funds, and they never would’ve been tempted to touch those customers’ funds.

LD: So Dave Setter ’82 — Dave compared what he calls the fantasy of Santa Claus to Sam’s fantasy, that of the corporation based on effective altruism. Now I’m going to leave it to you to say whether you agree that it’s a myth. He notes that parents keep their fantasy alive through lots of hard work like assembling bicycles late on Christmas Eve, and he asks this question, and I have an audio file from him that I’m going to play.

Dave Setter ’82: Having failed to understand the Santa Claus myth, specifically, how it can endure through what happens behind the scenes, did Sam Bankman-Fried miss out on an opportunity to fulfill his own myth, that of the EA based corporation?

ML: So for sure, the people at the center of FTX really believed in effective altruism. It wasn’t just a front or a ruse. For sure, they spent an awful lot of their time and brain power thinking about how they wanted to give away money, rather than just how they wanted to make money. You can argue with where they ended up in those arguments. It ended up being a very kind of curious movement. They were, ended up focused on existential risks to humanity. But they did, genuinely, see this thing as a machine for generating money that they would then give away. It starts that way, no question.

In the very beginning when Sam starts Alameda Research, he hires nothing but effective altruists. And they’re having, all the time, effective-altruists-like arguments. It was true in a way that I guess Santa Claus isn’t true, that there are actually effective altruists. It may be a myth, it may be a folly to think that you can run a corporation to give the money away. I don’t know anybody who’s really tried, set out in the beginning to make the money to give it away. Certainly not on Wall Street. I mean, there’s the idea of a financial corporation created to give the money away seems so antithetical to the spirit of Wall Street that it just seemed weird and funny when I first encountered it. But it’s also true that they got to a point where they were essentially pilfering their customers’ money to give it away. I mean only in the later days of the company, but when there was a collapse in crypto prices and they kept giving money away. So it ceased to be effective altruism, it became something else.

But I guess if his question is, did he miss an opportunity to preserve the myth by not putting enough effort into preserving the myth? Yes, I think that’s probably right. The way you would’ve preserved this particular myth is to keep it real, that there was a time in kind of middle of 2022 when Sam Bankman-Fried was faced with a choice. Crypto prices were collapsing, crypto lenders were demanding many billions of dollars back in loans from Alameda Research. He could’ve — if he just returned those loans and kept his hands off the customer’s deposits, I think he could have preserved the myth, maybe at the price of the myth of himself as a great trader. But yes, that might be true.

LD: I might attempt a follow-up question here. One of my colleagues at PAW was noting the Princeton connection of Peter Singer, who was one of the philosophers, right, behind effective altruism. Can’t really miss an opportunity to bring in —

ML: Of course not —

LD: A Princeton connection —

ML: No, it was fun to get in touch with him. I talked to him for the book because it was clear that the Oxford professors who spawned this movement in 2009 or whatever it was were operating in the spirit of Peter Singer. They were taking Peters Singer’s work and actually putting it into practice, actually saying that “no, philanthropy isn’t a nice thing you do. Charity isn’t an option. Charity is a duty, an obligation, that you have an obligation to give away what you don’t need to survive.” And the Oxford professors started to do it themselves. And then the Oxford professors started to proselytize the Peter Singer argument. And young people, particularly young mathematical people, found the argument appealing.

So he’s definitely the grandfather of the movement, and it definitely starts at Princeton. It’s funny because one of the things I asked him, when I talked to Peter Singer, was how did it play in the Princeton community? Was anybody threatened by your argument that if they go to Wall Street, they should only go to Wall Street to make money to give it away? And actually some kids did that out of Princeton. The first known person, to Peter Singer, to go to Wall Street to give the money away was Matt Wage, Princeton graduate of I think 2012, went to Jane Street and gave away what he made. But I asked Peter Singer, “Were people unsettled by this?”

And he said the undergraduates were always very comfortable with it. He said, I don’t think anybody else took it all that seriously. To the extent anybody was bothered, like I got blow back from parents for corrupting their children, taking them off the profit-making path. He said it wasn’t about the money, it was about food. Because he was also making an argument for veganism. And so kids would go home from his class and refuse to eat Thanksgiving turkey, and the parents would get upset. He said that was the only time he had kind of friction in his life in the Princeton community. But I was kind of proud of Princeton, that Princeton incubated this thing. You know, it’s not the most likely place, you would think, to generate this particular social movement, but it did. And Peter Singer’s responsible.

LD: That’s so interesting. What did Peter Singer think of Sam Bankman-Fried and what was going on over there? Did you ask him that?

ML: So I get into this story well before it all collapses, right? I mean, I’ve spent the better part of a year just loitering in the vicinity of the material, trying to figure out what it was and whether I was going to write a book about it. And it was then that I talked to Peter Singer. I didn’t talk to Peter Singer after it all blew up. I talked to him before it all blew up, and he was quite proud of the Oxford professors for actually putting into practice things that he had just argued in theory and himself had not done. He had given away money, but he hadn’t been as ideologically pure about it as they were, like measuring exactly what they needed to live on and giving away all the rest in the most efficient fashion. So he was very proud of them, and he was mystified by what Sam was doing. He was mystified that the thing had gotten so big.

Sam, when he was in high school, had determined he was a utilitarian of the Peter Singer type and had made a point of meeting Peter Singer, either end of high school or early college, and Singer had kind of imprinted him that Peter Singer meant something to Sam too. So Peter Singer’s, fingerprints are all over this thing. When things were going well, he thought, “This is great. Now it’s not just me writing about this. And now it’s not just a handful of Oxford Dons with their paltry salaries giving money away. It’s the richest person in the world under the age of 30 who says he’s going to do this. Maybe we have something real.”

LD: That’s so interesting. I sense another podcast coming on.

OK, so Geni Cowles ’97 says, “I’d be interested to hear Mr. Lewis discuss what, if anything, he learned about SBF,” that’s Sam, “and FTX during the criminal trial and how, if at all, that information altered his prior impressions of SBF.”

ML: When I wrote the book, I kind of knew almost everything that came out at the trial. This is going to be a squirrely answer. Let me try to recreate because I was at the trial for part of it. I’ll try to recreate what kind of surprised me.

It wasn’t like big facts. There was one little fact that disturbed me. It seems so dumb that I didn’t know, and it seems to be true. At the end of 2021, after Sam had raised money from venture capitalists, so it was wholly unnecessary, he got his closest colleague, Nishad Singh, to change their $950 million of revenues to $1 billion in revenues by ginning up some phony revenues because he thought a billion dollars sounded better. It was a bizarre and dumb thing to have done. One, because it’s illegal; two, because he didn’t need it for anything. It was just like he thought it would be fun to do. So that was the one kind of damning fact that I had not encountered.

But there were a couple of things that jumped out at me. One was just because it’s said on a witness stand doesn’t mean it’s true. It’s hard to get your mind around this. And the closer I’ve gotten to our system of justice, the more frightened I’ve gotten of ever being swept into it. It’s just like once you’re in it, you’re screwed. The feds charged, last year, 37,000 people or something with crimes and 99 point something percent of them either plead guilty or are convicted. Once you’re in, you’re done. Their powers are vast. And one of their powers, which not every legal system shares, is plea deals. And they made plea deals with three very frightened young people who told stories on the witness stand that were very different from how I remembered them.

I mean, I was there watching them through the period they were describing, and unless they were the world’s best actors — which they aren’t, they’re horrible actors — their states of mind that they describe in the three months or four months leading up to the collapse when they made it all sound a lot more premeditated and deliberate and that they were much more aware and it was more front of mind than it actually seemed at the time. The things these people who testified against Sam Bankman-Fried actually did with their lives — going on vacation, buying houses, having fun, working on the business —they seemed completely untroubled to me. They were describing themselves as just torn up and racked with guilt and so on and so forth, and it just seems highly implausible.

So I felt like they were allowed to misremember the tone of their experience, not so much that they lied in a way that they lied or said anything that was actually falsifiable, just remembered it differently for the sake of the prosecution. And that was a little frightening to watch. Because there’s nothing you could do about it. None of it just really excuses what they did, it just made it seem darker than it actually was.

The other thing that surprised me was I went in expecting to get an answer to two questions that I kind of have in the book, because the prosecution had the help, kind of oddly, of FTX, the bankrupt company, the people running the bankruptcy decided to just turn themselves into an arm of the prosecution and were supplying narrative and facts to the prosecutors, but not to the defense. And they had the ability to identify the moment when they would’ve dipped into customer funds. It’s not a simple matter that you have to think of this enterprise because everything was commingled. Think of Sam’s world, it’s FTX, it’s supposed to have whatever it is, $13 billion of customer deposits or $15 billion of customer deposits in it. And Alameda Research, which has lots of investments they’ve made, crypto trading profits, they’ve earned, but it’s all in one pot. The question that I had, that it’s important to answer for a bunch of reasons, was at what moment did the pot shrink below the amount that was owed to customers? At what moment, when the customers all turned up and asked for their crypto back, could this — Sam’s world — not have given it back to them?

The prosecutors sort of the way they sort of played the case was, that moment, is around June of 2022. So not long before it all collapses. So there are only four or five months there where it’s when they’re giving away money or spending money, they’re spending effectively customers’ money. But they never went in and actually figured it out what that moment was. And I thought the trial was going to answer that especially now that it looks like the customers are going to get their money back, with interest. I mean, you can make an argument, maybe, that there was never that moment, that net asset value was always positive. That they didn’t do that surprised me.

And the other question I had when I was sort of trying to figure out where the money went after it all blew up, and they were so loose with money. I mean sloppiness was just — it was just sloppy beyond belief. They’d have accounts with $1 billion in it and they’d forgotten they had the account kind of thing. I couldn’t account for a couple of billion dollars. It was just missing in my math. And it was crude math, very crude math, but nobody who I’ve presented it to who was an insider said my math is wrong. They all agreed, it’s like it doesn’t add up. We see the outflows, we see the inflows, and there’s a couple billion dollars. We just can’t account for it. I kind of thought that was going to pop up in the trial. Like, someone stole it. But it’s turned out that doesn’t appear that anybody’s stolen anything. I mean, there’s no secret accounts that are held by Sam Bankman-Fried or these insiders that the prosecutors turned up. So I was a little surprised by that.

But the trial, I got to say, I came out feeling, to the extent my mind was changed, it was more changed about our system of justice than it was about Sam Bankman-Fried, with maybe one exception. I’m sorry to go on so long here, but it was a big event. Sam is a social idiot in some ways. He doesn’t feel emotions the way people normally feel emotions. He’s had this thing on his whole life where he’s sort of numb to human feeling. This leads to a lot of curious social behavior, and he thinks — it’s sort of a byproduct of his sort of disconnectedness from other people, that he sort of feels like he can figure everything out for himself. He doesn’t really recognize grownup expertise to his, well, he didn’t have a CFO, he didn’t have decent accountants. He kind of thought they could just do it all themselves. They were as smart as anybody.

I didn’t realize just how infected he was by this idea until I watched him conduct his legal defense. He didn’t listen to his lawyers. No lawyer would’ve recommended he get up on the witness stand. And I thought, “Well, if he’s getting up on a witness stand, maybe he really knows something the lawyers don’t.” And he got up and he was just awful. He made things so much worse for himself and he, like them, he may not have said anything that was actually falsifiable, but you don’t not remember that you took a private plane to the Super Bowl, or you don’t not remember that you had dinner with President Clinton and the Prime Minister of the Bahamas. I was there for those things. I remember them, and I’m twice his age. I shouldn’t remember as much as him. So it’s just like he got up and didn’t remember all this stuff that he thought might be damning to remember, and the effect it created on the jury was like, you just see them think, “Well, this guy’s capable of lying. He’s capable of not giving us the whole story.”

So he made himself into the character, much more so than he’s ever with me. On the witness stand, he came across as more dishonest than I’ve ever experienced him in life. That’s not a smart thing to do. It almost felt like a death wish. So it made me wonder. It just made me wonder just how, maybe he has one. There’s a kind of martyr thing going on. So that was my thing. My thing, only the extent I thought differently about him at the end was just how foolish he was in the way he defended himself.

LD: I have another audio question. Kelly McGannon *06 has sent an audio file. I’m going to play it for you.

Kelly McGannon *06: Hi, Michael, Kelly McGannon, Class of 2006, art and archeology, Graduate School. Loved your book. The question I have for you is, knowing what you know now, what is the question you wished you had asked Sam very early on that may have shifted how you would’ve written that book, if at all? Thanks so much.

ML: I don’t think there’s any question I would’ve asked that would’ve shifted how I wrote the book. The question I wished I’d asked just to cover my ass, which nobody asked, is where is the money? It was funny because if you look back on it, everybody was suspicious about this operation when they first encountered it. Here is an exchange that you don’t just trade on, you give them your money, they hold it, they function like a bank. On the side of this exchange, the same dude who owns the exchange owns a private hedge fund that’s trading on the exchange. This is rife with conflicts of interest, but where my mind went, and where the minds of the venture capitalists who invested in him and the regulators who were thinking about regulating him and the journalists who were writing about him, where their minds went was, he’s giving Alameda Research some privileged access to information on the exchange. He’s giving them an edge against other traders. Maybe he’s even letting them see other people’s trades so they can front-run them, because that’s the sort of thing happens actually routinely on our U.S. exchanges.

But that wasn’t it at all. He was giving Alameda Research the money that belonged on FTX. He was allowing Alameda Research to use this money as free trading capital. It never occurred to me to ask him that question. So he didn’t lie to me, he just didn’t divulge it. But it never occurred to me to ask exactly where are FTX’s customer deposits? How are they safe kept? Who’s safe keeping them? How do I know if I put my money on the exchange that it’s not in some wrong place? He would’ve probably have lied to me if I’d asked. Although you never know. He might’ve said, “Because we can’t get bank accounts. It’s all in Alameda.” He might’ve said that, but I wish I’d asked that question because I would love to have had the answer after the fact. It was too late by the time anybody thought to ask the question.

LD: So Kelly also asks, “What questions do you ask to check biases and assumptions, either your own or those you post questions to?”

ML: So I always try to argue against myself, whatever thing I’m thinking, I try to take the other side and see how that feels. But the best way to check biases and assumptions is to find the people who actually hold opposing views. So I don’t just, in the year, in the bit that I spent in the runup to the collapse or the year and almost half in the runup to actually starting the book, I don’t just interview Sam Bankman-Fried over and over and over again, though I do that. I interview all the people around him, former employees who are angry with him, investors who’ve invested in him, regulators who think about regulating him, anybody who might have some other view and try to find stuff. The kind of questions I had about their business. This is in the book. I mean the material, the first six chapters of the book or so I don’t think would’ve been all that much different in a book where they don’t collapse.

I was already pretty tightly focused on that period in Alameda Research’s history where it all almost collapsed and half the people left because they thought Sam was either criminally negligent or actually a thief. The byproduct of this incredible sloppiness, this incredible lack of an adult supervision, that seemed important even before it all collapsed because it was clearly a chaotic place. So I ran down all those people who fled, accused Sam of being a crook, so on and so forth, before FTX collapses and got their hostility towards him before it all collapsed. And interestingly, most of them had backpedaled on their hostility. Most of them now thought he was right and they were wrong. He was now the world’s richest person under 30, and they were just a little too nervous about taking the risks that he was happy taking. Sam was smarter than they were. They’d kind of come around to that. So it made it very awkward when I went back after to collapse and they had to change their minds all over again. So you do that, you go find people who want to offer you different views of the subject.

In the end, it’s sort of like when you’re describing people, there’s no science to it. But when I have a character in a book, I start to feel comfortable writing that character. When I start to feel like I can predict what they’re going to do, when I start to feel, I know which way they’re going to jump in any given situation or with any given decision, and I feel like I know them, I could almost orchestrate how they’re going to go through the world. And I got to that point with Sam, mostly. I got to the point where I felt like I knew him and I knew just how dark or light his heart was. I roughly knew how he thought about the world around him, the extent to which he was honest or dishonest with the world around him, I didn’t — and it is some accumulation of interviews with lots of people and lots of time spent with him.

LD: So this is the question from the PAW staff, “Why do you think Sam kept allowing you access to him even after he was charged, and is he still talking to you?”

ML: I’m going to visit him at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn at 1:00 tomorrow afternoon.

LD: Oh.

ML: So yes, and I’ve spoken with him half a dozen times since his conviction. He’s allowed a 15 minute phone call every day, and I’ve had some of those. It’s a good question. Can I reframe it slightly?

LD: Sure.

ML: Why he gave me access at all. I meet him accidentally. I wasn’t seeking out a book subject. A friend asked me to evaluate him, a friend who was going to do a business deal with him. And I said to him, after I spent a couple hours, this is the weirdest freaking situation I’ve seen in a long time. You go from nothing in 18 months to having $22 billion. Your company goes from zero in two years to being valued at $30-something billion by venture capitalists, and you’re doubling every year, and it’s in the middle of this very squirrely space crypto. I said, “I just want to come watch.” I think he let me in the first place for two reasons.

The top of mind reason, and the one he could tell his colleagues was, “What need is approval with regulators. Regulators read Michael Lewis books. If we get a good book out of Michael Lewis, maybe they’ll approve our exchange.” I bet that’s what he was saying. I don’t know that’s what he was saying, but it was probably what he was saying. I think underneath that, there was actually an emotional reason, and I only found out this from his father later. When Sam was a kid, 10, 11, 12 years old, he read Moneyball, the book I wrote about baseball, and it made him feel important. It made him feel like his mind was suited to doing something as important as running a baseball team. And for a while, he imagined that’s what he was going to do with his life. So he felt some connection to me as a writer because of that book. So I think those are the two reasons he let me in.

By the time it all collapses, it’s a strange situation. The Bahamas, where this place was housed, was the site of this great flight in a matter of two or three days, an entire corporation had run off the island. I mean run, they’d flown off the island. But everybody was so scared because they didn’t know what had happened, and they thought they were going to get arrested. They all went back and hid in their parents’ basements. This is the first financial crisis where all the perpetrators ran home to their parents and went to their old bedrooms and went under the bed and put their hands over their eyes and hoped no one would see them. That was the tone of the thing.

The only thing left in the Bahamas, when I rolled in the day he signed the bankruptcy papers, Friday in a bad week that had started on a Sunday. The only people there were his parents, his shrink, one or two odd employees, and then me. He had no one to talk to. So I think part of it was he was lonely, and part of the reason he let me continue to hang around, part of it was I had passes, I had codes to all the buildings, so it was going to be hard for him to keep me out. Part of it was, it wasn’t like he was shy talking to the press then, he was trying to talk his way out of it. So he was talking to all kinds of people. Part of it was he thinks he thought I had something of value at that point. I had some context for what had happened. So I knew the players in a way that, and it is true in this case, nevermind me, everybody inside that place who was close to Sam and to the company, the people who ran it, his employees, those are the people who actually were the most damaged here. They’re the ones who lost all their money and often their parents and their cousins had put money on the FTX, and they lost their reputation, and they lost their jobs. Those people who probably deserved to be the angriest at Sam for how he ran the place, almost all of them are mostly sad. They’re mostly like, they understand, they don’t think he’s at heart, a deeply evil person. It’s like, this just started out as a good thing and it went wrong.

My point is that the closer you get to it, the more intimate your knowledge is of the whole situation, the more you feel a kind of sympathy. It isn’t that you forgive him and think it was all OK or anything like that. It’s just you have a context for it and you understand it in a way that you don’t if all you do is read Twitter. And he was dealing with a lot of journalists who all they did was read Twitter. And so I think he thought, at the very least, I might offer some context. He probably thought there might be some benefit to that. I doubt there was. I mean, I don’t think my book helps him at all. Maybe helps him after he gets out of jail, but it didn’t help him with the legal process at all.

LD: Did he read the book?

ML: He did. And how do I know that? I know that because, we’ve spoken, but we haven’t spoken about the book. His lawyers told me they smuggled it in during the trial with a bunch of legal documents. And what I do know is that he’s in a cell with 30 other people. He’s being kept in a cell where they keep the prisoners who would be at risk if they were in the larger population. And as Sam said, it’s more diverse than the freshman class at Harvard. It’s crazy who’s in there. Former president of Honduras, former attorney general of Mexico, four former assassins for drug cartels and U.S. gangs who killed so many people that if they’re in with a general population, someone will kill them as an act of revenge. It’s a weird group of people. People have been accused of pedophilia.

But that group, the day before the book came out — they don’t have much to entertain them in there. They have a ping pong table, a few payphones and a TV set. That group gathered around the TV set to see the 60 Minutes piece about my book. And I know Sam watched that, so he got a kind of a little bit of a skinny on the book from that. I also know that after that, the prison guards started to ask him for crypto trading advice. And that several of his cell mates are using him as a kind of venture capital adviser because they have business plans that they want to get funding for. So he is helping them write their business plans. So I don’t know he’s read every word of the book. I know he knows roughly what’s in the book.

LD: That’s so interesting. OK, so I have two questions here that are kind of on the same subject. So, at the risk of throwing too much at you. I’m going to ask them both, and hopefully it’s not too much because it’s kind of all one question. OK.

ML: Yep.

LD: Our managing editor at PAW, Brett Tomlinson asks, “You have your own podcast series, Against the Rules, which has covered topics of fairness, including the role of referees, and most recently covered the trial of Sam Bankman-Fried. Broadly speaking, do you think Sam has been treated fairly by the judicial system, and given the charges he’s been found guilty of, what do you think a fair sentence would be?”

Now I’ve got a follow up, again, I hope this isn’t too much. Susan Rhoades *92 asks, “Given the increased market value of assets likely to be returned to former FTX customers, do you think this will improve or shorten the sentence handed down soon on March 28?”

ML: I’ll take the second one first. There’s been no outside examiner, until just recently, until the last few weeks, appointed by the bankruptcy court. Sullivan and Cromwell, who was Sam’s lawyer before it all collapsed, has been allowed to control, run the bankruptcy charging $1.5 million a day in fees and control the narrative of what happened there without letting anybody in to see the documents, see the evidence. I mean, their incentive is for this to go on as long as possible because they get paid by the hour. Their hand’s been forced by obvious value in the holdings. Like people have seen that, oh God, Sam Bankman-Fried actually bought a 20% stake in Anthropic, the AI company. That’s in there that seems to be worth billions of dollars. Why aren’t we getting our money back?

A few weeks ago, the bankruptcy lawyers and the guys running the bankruptcy went into the court and admitted that basically everybody’s going to get their money back. All the depositors are going to get their money back, with interest. And before they did that, it was kind of obvious that was true because you can actually trade your claims. If you had $1,000 on FTX the day it all went bad, you could have gone and sold your claim — for pennies, you wouldn’t have gotten very much. Now you’ll get 85 plus cents on the dollar because the people who evaluate these claims and kind of know what’s in there and realize we’re going to get it all back. Actually that’s been apparent for some time.

The question is, why are you going to get it all back? I think the simple explanation is he was sitting on a bunch of crypto-like assets and crypto’s gone up. But I don’t think the simple explanation may be true. John Ray, the guy who’s running it, has told me a year ago, more than a year ago, that he just found all this money that Sam and his colleagues didn’t even know they had, like accounts that they had lost track of, and in gathering up these assets, he’d found seven and a half of the eight and a half billion dollars that were owed customers. I wouldn’t be surprised if they’re sitting on twice what they owe customers or some amount over what they owe customers. So, that — you would think that would change the way you feel about Sam Bankman-Fried’s sentence. If everybody’s going to get their money back, he still caused damage and harm and all the rest. He still misled people about where their money was.

I’m told by lawyers that the judge doesn’t care. The judge is thinking of this as, “Oh, you robbed a bank and you happen to have bought a lottery ticket with it and the lottery ticket paid off. You don’t get credit for that.” So the judge is going to treat him as if the $10 billion or whatever were missing, or seemed to be missing in the beginning, are still missing. And the betting money is the prosecutors are asking for 50 years. The defense is asking for six and a half, and the betting money is, it comes in around 30. Just like an informal poll of lawyers.

Do I think that’s fair? I don’t.

But let me just give you a little background to that. Part of my problem with discussing the subject is you got to have a discussion about what the purpose of prison is. I mean, is Sam Bankman-Fried to threat to the world if he’s not in prison? No. Does he need to be punished as a deterrent? Yes, probably. He needs to spend time in jail so that people who are thinking about stealing other people’s crypto think a bit before they steal other people’s crypto. What sentence? At what point, if you raise the sentence, does it add no deterrence? Does it matter for the deterrence value if it’s 10 years or 100 years? I think probably not. I think the mere fact he’s going to jail is the big thing, and anything over a few years is superfluous.

So I think about it that way. And I think we put people in jail in this country for, it’s just silly how we use jail. We put people in jail at rates that no civilized country does. So you’re getting my point of view on all this. But five years, somewhere between five and eight, something like that, seems about right to me. I don’t think he shouldn’t go to jail. I think he did stuff he shouldn’t have done. He’s convicted, he’s guilty. But I think what feels fair to me is a sentence closer to what his lawyers are asking for than what the prosecutor’s asking for. It’s going to feel bizarre if he’s sent away basically for life, and everybody gets their money back. I just don’t get that. So that’s my view.

LD: I think that would be a great place to end this conversation, but I just can’t let you go without one more thing.

ML: OK. Yep.

LD: Who said Donald Trump would stop running for president for $5 billion?

ML: So I think —

LD: And is it true?

ML: In this case, I’ve let the reader know that I don’t know how true this is, but this is what I think happened.

So Sam Bankman-Fried was toying with the idea of paying Donald Trump not to run for president. This was two years ago. And so two years ago that looked like, possibly, Trump might actually do that. He wouldn’t do it now. But the line of communication between Sam’s political operation and Trump was Sam’s CEO, who was a Republican named Ryan Salame was chummy with Donald Trump Jr. And I assumed it was conversations between those two that was leading to a number, and the number where they were was 5 billion. But there were these other conversations going on, and it was between Sam and lawyers who were trying to decide whether this was even legal. I mean, essentially you’re bribing someone not to run for president. I don’t know if you can do that.

My immediate reaction, I remember sitting across from Sam on a plane and my first reaction, thing in my mouth was, “This is stupid. Why would you do that? You know what’s going to happen, you’ll give him $5 billion, and he’ll run for president. This is an unenforceable contract, so don’t. Just don’t even do this.” But he didn’t listen.

So, I think it’s true. I think it’s certainly true that people close to Trump, were having the conversation with people close to Sam and they got to $5 billion as maybe that’s the right number. Do I think Trump actually sat there and said, “Oh, I’ve got to think about that”? I don’t know. I don’t know.

LD: Gotcha. All right. Do you want to tell us what your next book is going to be about?

ML: I don’t know. I don’t know, I always take a little time off between them. I do think you’ve got to leave yourself the space to not write a book. So you aren’t just doing it because you have to do it, like a senior thesis. With no obligation comes the possibility that — you leave yourself open to the idea that you only write these things because they need to be written rather than you have to write one. And I feel that way about them. So I’m waiting for whatever it is that might need to be written.

LD: All right. Very good. Well, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us today.

ML: Totally fun.

LD: Really appreciate it.

ML: Thanks for not making me sing “Old Nassau.”

The PAW Book Club podcast is produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly, and anyone can sign up through our website, paw.princeton.edu. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode, also at paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.