Come with me to the lands of mystery, history and romance.

— Lowell Thomas *1916, with Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia, 1919

We sometimes slight in these historic reflections topics which are not an explicit part of the Princeton curriculum. We have rarely delved into medicine or the legal profession, and the same neglect, I fear, is true of journalism, which qualifies as irony here at one of the longest-standing alumni publications in the universe. But in this era of endless conflict over truth, lies, transparency, and even physical danger to our reportorial brethren, we really should gather up a small piece of the courage of our sister Maria Ressa ’86 and consider why this field should be valued, and from an intellectual point of view how Princeton can and has fortified it to do the nasty, gritty work that is the bedrock of modern communication in a free society.

If you wander over to Rappler, Ressa’s current journalistic effort online, you might be hard put to understand why there would be any brouhaha. But in her native Philippines, it seems to provide the government an excuse to harass her and anyone she smiles at. The current president’s draconian method of dealing with perceived drug pushers makes this something more than a vague danger. Having already faced a series of trumped-up attacks through the Filipino regulatory and court systems, Ressa and her internationally praised operation — she was one of Time’s people of the year in 2018 — are currently standing under conviction for cyber libel, and she’s subject to years in jail pending appeal.

Why are the stakes so high? Well, let’s cut out a whole ton of exposition here and just note one word: Facebook. Ressa was one of the first, during various international crises that reached the Philippines during her time as a correspondent with CNN, to understand the social media site could be used to marshal the populace, to alert users instantly to breaking news and issues, and to focus popular opinion. And Rappler began as a creature of social media, which it remains despite broadening to maturity on the website.

This is the historic aspect of journalism we examine today — not just telling the news to an interested public, but the constantly evolving platforms upon which that is attempted, and how each has potential for good, ill, or both in capricious combination. Philip Freneau 1771, armed with a First Amendment that essentially no one else in the world enjoyed in his time, chose to be a partisan voice — very talented in the new world of broadside Capitol press, but partisan nonetheless — and brought his nascent career to an early end. At the birth of yet another medium, the newsmagazine, Hamilton Fish Armstrong 1916 chose in 1924 to scrupulously play it down the middle with Foreign Affairs and reaped decades of respect and referent power in the diplomatic community. Frank Deford ’61 was much the same in the context of true sports journalism, which had arisen from great newspaper writers such as Ring Lardner and Grantland Rice, but reached its zenith with the creation of a separate Sports Illustrated under the Time umbrella in 1954; his reputation was not only huge, but scrupulously fair.

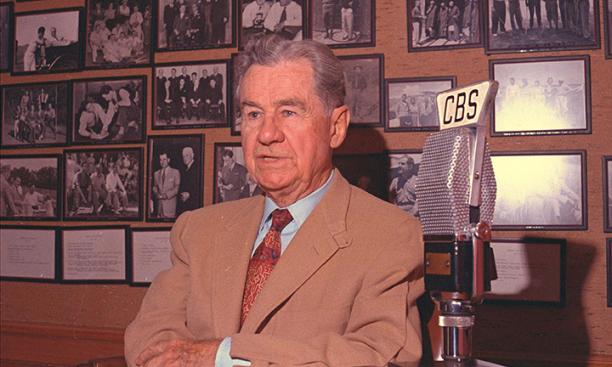

So what are we still missing here in our evolution of journalism? Of course, it’s that marvelous double-edged sword of the 20th century: broadcasting. And it may surprise you to learn of the outsized effect, continuing to this day, of the first great Princeton multimedia star (long before multimedia was even a thing), Professor Lowell Thomas *1916.

Wait, what? Professor?

The undergrad curriculum in the 1910s certainly gathered pizzazz after the preceptors invaded in 1905. On the receiving end you had folks like F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917 and Edmund Wilson 1916, and on the pitching end lights like Alfred Noyes and his poetry and, yes indeed, Thomas’s public speaking class — oh excuuuuuuse me, “oratory” class — a way for him to minimize his tuition for the master’s grad school program. To call him a tireless self-promoter is like calling Frank Gehry an unusual designer. Thomas (having already worked as a local reporter) graduated from his Colorado mining-town high school in 1911; by the time the United States entered World War I in 1917, he had two bachelor’s and two master’s degrees, the last from Princeton which he felt would open doors for him, which indeed it did. He also had written for three years for The Chicago Journal, taught oratory for four, and invented the idea of the travelogue on a (free) train trip to Alaska, thinking about how great a film of the trip would be if narrated. In a world without commercial aviation, doing all that seems impossible, but it did set him up for Woodrow Wilson 1879.

When the U.S. entered the war, President Wilson needed coverage (let’s not say “propaganda”) and he sent a batch of writers to provide it, including the 25-year-old Princetonian Thomas. Having instantly diagnosed the Western Front as dull as mud — literally — he headed for the unknown reaches of the Middle East, where the Allies were fighting the Ottoman Empire. The result, in summary, was Lawrence of Arabia. Arthur Kennedy’s film reporter Jackson Bentley (“You answered without saying anything. That’s politics.”) is a fictionalized Thomas. After the War, Thomas essentially created the legend of T.E. Lawrence through a theatrical exhibition of silent newsreel footage, narration, and orchestra that toured America and London, even landing Lawrence on the delegation to the Paris Peace Talks. Introduced by the dramatic teaser you see above, no such mixture of reality and high drama like it had ever been conceived.

Thomas edited a couple of magazines to fill in his spare time as he wrote 11 books (two on Lawrence) between 1924-29, but was poised for action when sound film was perfected and Fox created Movietone News in 1927 — he narrated the newsreels for tens of millions of cineastes with somber authority for 25 years. He also experimented with radio almost the day on-air news programming began, and had his own nightly national program, essentially the blueprint of a newscast, in 1930. That weeknight program ran without interruption from many places around the world until 1976, following the award of his Presidential Medal of Freedom. His intro each night — he was, of course, the first to have one — was a warm “good evening, everybody.” He dabbled in television (he narrated the first televised political convention in 1940), but radio allowed him to restlessly travel to Tibet, World War II Berlin, the Arctic, you name it, while filing reports.

From the beginning, across these media, he religiously played his reporting straight (like Armstrong), avoiding overt partisanship wherever it lurked, essentially creating daily the American “tradition” of unbiased electronic journalism — when he had come on the scene, the yellow journalism of Hearst and Pulitzer had been by far the most popular model. Thomas was in fact Cronkite, Huntley, Brinkley, and Koppel before they existed, and in many ways their creator. But of course, that would never have eventuated had he not been first and foremost an ingenious oratorical showman and an indefatigable self-promoter; and that combination of scrupulous impartiality surrounded by chaser lights and a 40-piece orchestra does not commonly occur in nature.

It is also the combination that now is put forward by Ressa and others who seek to use the volatile modern media, reportorial and social, to espouse freedom and humanitarianism across a globe that often resists them with malevolence. Is this courageous, altruistic, or foolhardy? We leave that to you, the Informed Historian, to judge; but we also note the caution popularized by Bob Woodward, which has now become the official slogan of The Washington Post, “Democracy dies in darkness.”