“We were talking about the love that’s gone so cold

And the people who gain the world and lose their soul

They don’t know, they can’t see, are you one of them?

When you’ve seen beyond yourself then you may find

Peace of mind is waiting there

And the time will come when you see we’re all one

And life flows on within you and without you.”

— George Harrison, June 1967

Those of us who frequent Reunions weekend almost every year become fussy about details, but I must say if this year’s weren’t the best ever, they were within spittin’ distance, as Grandma Fern used to say, with astonishingly nice weather and interesting people (and ideas) wherever you turned. And our good buddy Dr. Joe Schein ’37, still practicing psychiatry at 102 years old, returned to the P-rade to win the Class of 1923 Cane for his second year, becoming the sixth alumnus to march in the P-rade at his 80th reunion or later. The others have been Arthur Holden 1912, Evan Miller 1917, Leonard Ernst ’25, Malcolm Warnock ’25 — who eventually returned for his 87th — and Pete Keenan ’35 *36.

We also really needed Reunions; it seems far more than a year since Schein’s last walk down Elm Drive. Last year at this time, in my summer P.S. I noted that public political discourse (and that was just primary season) was odder than anything since Andrew Jackson’s Big Block of Cheese, but in retrospect I understated. The current myopic utilitarian mess not only lacks decorum, but any sort of moral center (that’s the current buzzword) that might give some clarity of purpose. It’s infuriating, since such a moral imperative (I like to think more in the traditional Immanuel Kant form) isn’t insurmountably difficult to determine for oneself, and to succeed doesn’t need to be identical with other folks’. Good examples are always near at hand.

Reunions coincided with the 50th anniversary of the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, foreseen as a pop-culture event. The Beatles were on their way from “She Loves You” to “All You Need is Love,” and while philosophical signs were seen earlier on Rubber Soul (“Nowhere Man”) and Revolver (“Eleanor Rigby”), the eruption of Sgt. Pepper as a deconstruction of British society and the human condition — along with its arresting music arrangements — was a monument of such moral heft that most folks just enjoyed the tunes, then perhaps returned to think it over days or years later, and then became even more enmeshed in the humanity. The brutal challenge of Lennon and McCartney’s climactic “A Day in the Life”— how can we all do this better? — is so serious it defies understanding the first time through, especially because it’s so damned entertaining. But it has the same moral imperative as the rest of the album, which is most overt in George Harrison’s exotic “Within You Without You,” whose closing admonition you see above. You don’t need thousands of government employees to develop a moral imperative, you need a clever producer and four high-school educated musicians with empathy.

Then there’s our friend Bob Dylan (honorary Ph.D., 1970), whose moral compulsion has always been clear — listened to “Masters of War” lately? — but who is now, as an Anti-Elder Statesman, being officially treated as a literary figure, which is hardly news to many of us but still odd. In his recent delayed lecture for his Nobel Prize, he notes the sources of his moral sense, inextricably tied with his need to express it as an interwoven part of his worldview. Was it the Cold War, with its intricate game-theory strategy? Was it international economic profligacy and cultural malaise? Was it the military-industrial complex? No. It was Moby Dick, it was All Quiet on the Western Front, it was The Odyssey; he calls them grammar-school reading. Of course, they’re far more, but it’s worth noting that drawing moral imperatives from them need not go beyond that; it needs only your imagination.

Reviewing our sojourns here at Rally ’Round the Cannon since the Big Block of Cheese plaint a year ago, I find that I’ve likely internalized concern for moral imperative and sought to consider facets that might identify it and its effects in our common experiences at Princeton. We started, by coincidence, with overt Enlightenment ideas (here comes Kant again) in the Declaration of Independence, and later in the American Revolution that depended so desperately upon it. There was the intriguing exercise of emotionally inculcating freshmen into the Princeton universe, and of the fervent endeavors of those bitten by the Triangle bug “to taste the true wine of being an American,” as Josh Logan ’31 put it. We examined the importance of multifarious languages in the Princeton moral construct; and the many indications that Princeton and the global community are deeply interdependent, in terms of both our students and our alumni. We pointed out the repugnance of sexual — or any personal — harassment to the moral community, and examined how historical slighting of women and other minorities has unfailingly returned to bite us in the rear. And we restudied, not for the last time I’m sure, the eternal American moral imperative of free speech, which has always served us well, and embarrassed us on those few occasions when compromised in the least. In looking back on these, it strikes me that, when Princeton does not offer a compelling moral imperative, it doesn’t offer much of anything.

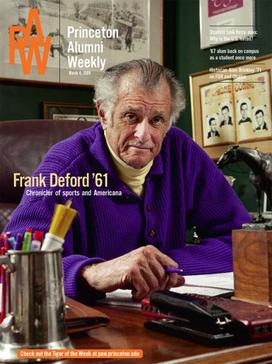

Now, the wizardry of his prose was one thing, but Deford’s well-developed — and strongly expressed — sense of values was a huge step beyond the norm for sportswriters, the type of global vision you saw in Jimmy Breslin’s early writing before he wandered away from sports. Deford thought soccer was a bore (I wonder what he thought of cricket?), he thought football was dangerous, he thought most locker-room interview drivel was, well, drivel. And his interests in life were broad enough to supply excellent analogies and context to the strangest sports item. His 1976 piece sneering at the Christian Right’s efforts to proselytize through high-profile sports is powerful now; at the time it was brave as well. The subtle implication was that sport, well executed, was probably more moral than most of organized religion. Then there was the time when Princeton athletic director Gary Walters ’67 declared that athletics, done right, was akin to art. That, of course, is a relatively common view in the Ivy League, at least on a symbolic level, but he got plenty of flak from the sporticulture. Deford, in his role as sports commentator on NPR, a match truly made in hoops heaven, leapt to Walters’ defense, and while skewering the moral bankruptcy of big-time college athletics along the way, inquired simply, “Is not what we saw Michael Jordan do every bit as artistic as what we saw Mikhail Baryshnikov do?” There are many folks at Princeton who are attracted to, or at least tolerantly appreciative of, the role of college varsity sports because of the impressive examples of such alums as Hobey Baker 1914, Pepper Constable ’36, Dick Kazmaier ’52, Bill Bradley ’65, John Rogers ’80, or Ashleigh Johnson ’17. I highly suspect that, especially by giving voice to their moral imperative, the same can be said of Wolff and Deford and their fellow journalists as well.

Princeton’s ability to engender moral thought and behavior in its community members is a comfort, and a continuing challenge to emulate, be it President Eisgruber ’83’s stand on the need for strong international presence in the community, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski *61’s efforts to improve the lives of his fellow Peruvians, Wendy Kopp ’89’s Teach for America, or Deford’s contempt for a sport that has tens of millions of fans and makes billions of dollars but damages its players’ brains in the bargain. A moral imperative is probably the only satisfying philosophical reason why we’re here, why there is a Princeton; why the devoted New Lights, with their vision of self-reliant and responsible mankind, who dreamt this up way back in the 1740s might still consider it all worthwhile.

Dei sub numine viget.

And so to another richly earned summer breather for the long-suffering folks at HQ who try to decipher my chicken scratches for each thrill-packed episode of Your Favorite Periodical. Assuming however that you, the Seasoned Historian, wish to keep your wits and repartee at their finely-honed best, we note our usual irresistible menu of learned activities to widen your vistas and/or hat size over the interregnum. You could take your pick of any of this year’s columns referenced above that you may have missed and perform an erudite analysis (remember, this is post-grad education, the analysis must be longer than the source material). Or you can join the newbie Class of 2021 in their freshman Pre-read, the über-timely What is Populism? by politics professor Jan-Werner Müller. Or this year, we present a new and possibly unique alternative: Write and tell us, in 25,000 words or less, why you think you and your fellow alums – seemingly out of nowhere – blew the doors off all historic Annual Giving Campaigns in 2017 in terms of dollars raised, after a few years in a relatively narrow although highly generous range. As per usual, there will be a pop quiz in the fall.

As the Tempos put it, “See You in September.”

No responses yet