“Never was there a more interesting period than the present.”

— Philip Freneau 1771, The Jersey Chronicle, 1795

One reason I think the beneficent editors of Your Favorite Periodical were most wise (grovel, grovel) in their choice of this year’s theme-issue topic — journalism — is that we are at a self-aware moment in history, when we are repeatedly motivated to pause, look back, and reflect on where the peculiar and ancient American version of the fourth estate came from, all the better to divine where it might be headed, if not indeed to step in and guide it toward a healthy goal.

Thus, a couple hints. We aren’t talking Twitter. We aren’t talking Facebook or Instagram or blogs. Those are merely tools. In fact, we really aren’t talking “citizen journalism” at all, mainly because the term is hopelessly confusing. It seems to imply any citizen with a smartphone is a journalist, and that’s rubbish. A journalist may ply her trade with a smartphone, and is likely a citizen, but that’s coincidental to providing good journalism. So what is “good journalism” then, you the wise historian reply with perspective, if not simply content? In the immortal words of Justice Potter Stewart, I know it when I see it. (We will bypass for the moment the fact he was actually discussing pornography.)

Now, one major reason we’re currently motivated to look back at the “good olde days” of journalism is the conceit that the Golden Days of Watergate (or whatever) reflected a type of moral, objective journalism that in fact is a pipe dream. Language is not truth, it is symbolism, and words are not things, they are symbols. Symbols inherently have approximating limits, and may even change from culture to culture, and so misunderstanding and alternative words/symbols are always involved, and — presto! — you have bias and ambiguity. They are as symbiotic to journalism as those weird little critters in your gut are to digestion, and often similarly attractive. The yellow journalism of Pulitzer and Hearst isn’t an aberration, it’s journalism; the irony that Pulitzer turned around and in 1912 started the Columbia Journalism School and the Pulitzer Prizes (which in turn came to idolize objectivity) can be seen as aspirational, perhaps, or simply good comedy, like a global Peace Prize donated by the inventor of dynamite.

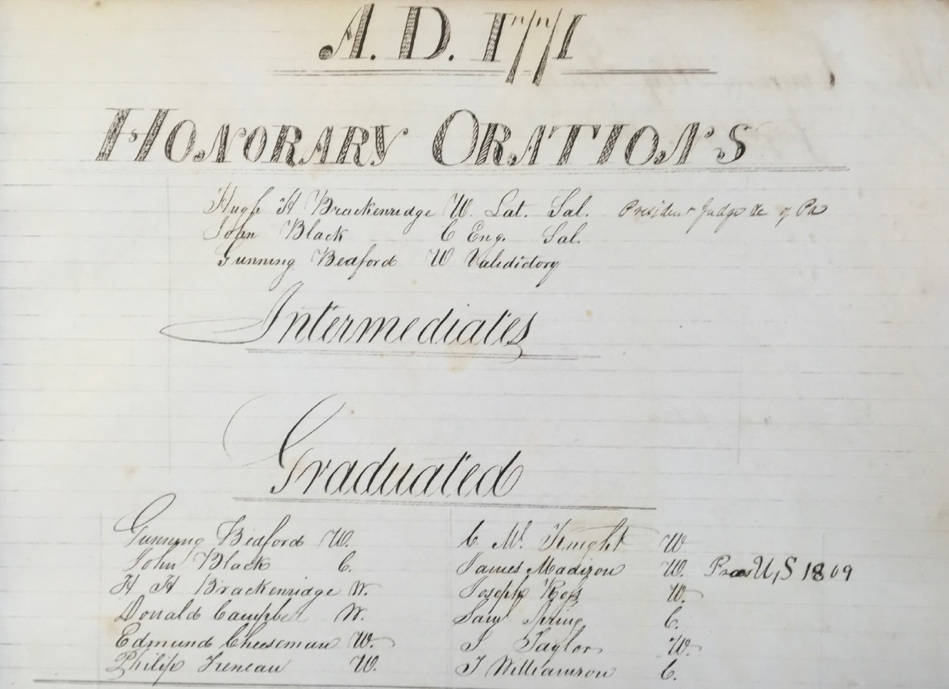

Which brings us to Philip Freneau 1771.

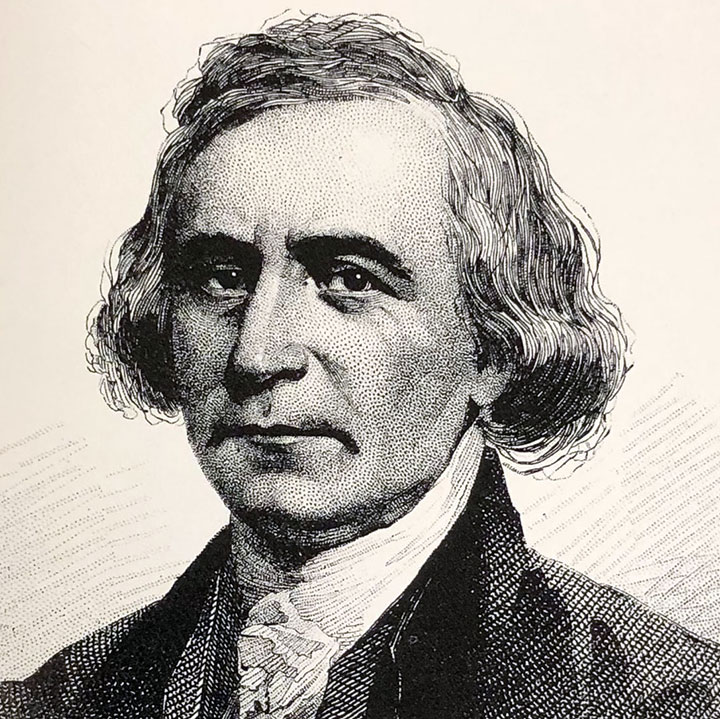

Whoa, you say, let’s just hang on a sec, I’ve read all the weird stuff the Princetoniana Committee sends out, and he was the Poet of the American Revolution, and James Madison 1771’s best buddy, right? Correct you are, but as it happens we are also talking about one of the more peripatetic personalities of the 18th century (which is saying something, given his fellow publisher, Ben Franklin). The list of occupations Freneau couldn’t stand — and he seemingly tried everything at least once — notably included teaching and the ministry, where you have to periodically sit still and contemplate, or at least behave. Meanwhile, the stuff that really caught his fancy tended to be restive and outside the norm, the descriptor “first” following him around from the day he got to Princeton — first member of the American Whig Society, first American satirical novelist, first war poet, first transcendentalist poet, “father of American literature,” and our personality focus du jour, the first Democratic-Republican news editor of the 1790s. Let us delve.

Freneau, a Jersey boy schooled by William Tennent Jr., New Side Presbyterian trustee of the College, arrived in 1768 as a 16-year-old sophomore with poems already in hand. He found under the newly arrived John Witherspoon not only a hothouse for his political fervor, but a community of young radicals who could amplify his decidedly non-clerical literary proclivities. A batch of them took one look at the dominant conservative Cliosophic Society on campus, and formed the American Whig Society to oppose its every move and thought. Madison, the Virginian, was one, William Bradford 1772 (who was three years younger than Freneau), the future attorney general of the United States, another; and then there was Hugh Henry Brackenridge 1771, an imposing Scotsman four years Freneau’s senior, who became his intellectual and literary co-conspirator. Freneau and Brackenridge wrote Father Bombo’s Pilgrimage to Mecca in Arabia, a slightly disguised political satire skewering the Cliosophs at every turn — and just in passing was seemingly the first sizable work of prose fiction in America. They then turned to an epic patriotic poem, written primarily by Freneau and delivered by Brackenridge at Commencement in September 1771, unsubtly entitled The Rising Glory of America. Running about 40 minutes, the ode predicts a great and idyllic nation stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific, ending with these lines:

The final stage where time shall introduce

Renowned characters, and glorious works

Of high invention and of wond’rous art,

Which not the ravages of time shall wake

Till he himself has run his long career.

READ MORE: The Fabulous Class of ’71 (1771, that is), by Sean Wilentz

Brackenridge went on to essentially invent Pittsburgh, as founder of The Pittsburgh Gazette, the first major newspaper away from the Atlantic Coast, as a founder of the University of Pittsburgh, and as chief justice of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, all the while publishing a stream of political sermons and flyers, as well as his major work Modern Chivalry, a quixotic comic adventure describing how stupid people beget corrupt leaders.

Freneau was slower off the mark, writing various satires against the British, but then restlessly (surprise) removing to the West Indies from 1776 to 1778, writing nature poetry and learning complex sailing and navigation. Just as suddenly returning to the country at war, he signed on to the New Jersey militia, captained a ship as a privateer, and promptly ended up on a British prison ship for six weeks. Enraged, he set off on 10 years of concentrated essay and poetry composition, glorifying the Revolution and castigating the British, but also putting out a steady stream of atmospheric poems that foreshadowed 19th-century American Gothic, transcendentalist, and romantic primitivist verse before most of their principal artists were even born.

Then he got married. [Please send your plaints to PAW directly; here at History Central, we report, you decide.] This seemingly led to an attempt to rationalize his life by entering the newspaper-editing world, perhaps a bit too orderly and repetitive for him, beginning with the unremarkable New York Daily Advertiser in 1790. But then his populist friends in the government, notably Madison and Thomas Jefferson, began to pressure him to come to Philadelphia and create a counter-publication to the Gazette of the United States of John Fenno, a quasi-official party newspaper that carried the thinly disguised writings of many of President George Washington’s Federalist government officials, including Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton. The temptation became too strong, and Freneau began The National Gazette in October 1791, beginning as more of a government-proceedings reporting vehicle, but quickly morphing into an ardent supporter of the Republicans, not to mention the French Revolution.

Freneau criticized Hamilton’s financial policies as “numerous evils … pregnant with every mischief” and attacked the public celebration of Washington’s birthday as “a forerunner of other monarchical vices.” Washington couldn’t contain himself, grumbling publicly about “that rascal Freneau”; at least he didn’t mention “fake news.” Using a pseudonym, Hamilton attacked Freneau through the other Gazette, using as a lever Freneau’s $250 government salary from Jefferson as a translator, and implying bias. This drove Freneau to nastier opinion pieces and more slanted articles, and then came Citizen Genet. When the new French emissary started raising his own army and navy in the South in flagrant contravention to American neutrality between France and its enemies Britain and Spain, even Hamilton and Jefferson united to oppose him, but Freneau held firmly to supporting Genet. As the issue became toxic, Freneau’s language coarsened, and in 1793, after a two-year run, the National Gazette closed down to install new modern type in its plant, then never reopened; its subscribership was certainly on the wane.

What the Democratic-Republicans wanted was someone with the editorial vision of a Roger Ailes; what they found was a wildly creative politico who needed someone else to hold the editorial reins — a Keith Olbermann, perhaps, with a sprinkling of Voltaire. And while as we noted objectivity may necessarily be an ephemeral state in journalism, consistency and product discipline are different matters.

Indeed, Freneau tried a few less-partisan editorships down the line, both in the Big Apple and in his home base of Mount Pleasant, N.J., now Matawan. None lasted as long as his two years at the National Gazette.

Jefferson, who said Freneau had “saved our Constitution which was galloping fast into monarchy,” took over the presidency in 1801, and curiously, Freneau did not set up shop in the capital, staying home in Jersey instead. He alternated bouts of writing, mostly crotchety anti-corruption essays, with stretches back at sea, in touch with the solitude that somehow seemed better for him than the halls of government. He lived until 1832, but virtually none of his 19th-century poetry can stand up to his romantic verse of the 1780s. Literary critics diverge to this day on his importance and his talents, but all seem to agree that somehow, perhaps without the existential politics of his age, he could have done much more.

No responses yet