The Fabulous Class of '71 (1771, that is)

Consider a class of Princeton students that included a future president of the United States; a writer later hailed by critics and scholars as one of the greatest (and possibly the very greatest) American poet of his time; and a patriot who wrote what is arguably the first American Western novel, when the American West still lay east of the Mississippi River. Then consider that the president-to-be was James Madison. Consider that the class’s less celebrated members included one of Madison’s future fellow framers of the U.S. Constitution, as well as a future Presbyterian clergyman who would help ratify the Constitution in Pennsylvania's state convention in 1787; and that still another graduate would become one of President Madison’s more outspoken critics in New England during the War of 1812. Finally, consider that the entire class (including one student who transferred to Harvard) numbered only 13 young men.

This is Princeton’s Class of 1771 — the most illustrious graduating class ever in the history of Old Nassau and, for that matter, in the history of American higher education. More than any other, the Class of 1771 anticipated the motto that Woodrow Wilson 1879 would proclaim at the end of the 19th century: “Princeton in the nation’s service.” Indeed, the Class of 1771, more than any comparable group, created the nation, in poetry and prose as well as in politics.

Madison, the class’s most illustrious member, nearly did not make it to Princeton. Young Virginians of his background and aspirations — Madison’s father was a prosperous tobacco planter and slaveholder — traditionally attended the College of William and Mary. But Madison’s family had differences with the administrators of the Virginia college, and the intellectual renown of John Witherspoon — Princeton’s new president and a future signer of the Declaration of Independence — quickly spread across the colonies when Witherspoon arrived from Scotland to take up his duties in 1768. In the summer of 1769, the precocious Madison set out for Princeton, where he would begin his studies with a sophomore’s standing and then combine his junior and senior years into one, graduating in the fall of 1771.

In contrast to its later reputation as the northernmost college for southern gentlemen, pre-Revolutionary Princeton was known for drawing its student body from all parts of the colonies, unlike Harvard and Yale. (Of the 11 whose biographies are known with certainty, only one other member of Madison’s class was raised in the South, two came from New England, and the rest were raised in the “middle colonies” of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.) Madison quickly fell in with three kindred spirits. Hugh Henry Brackenridge, a strapping farmer’s son from backwoods Pennsylvania, showed great wit and oratorical skills as well as an ability to defend himself with his fists. Sterner in demeanor, Philip Morin Freneau arrived in 1768 (like Madison, as a sophomore), but he still was in mourning for his father, a New York City merchant, who had suffered severe financial losses and died a year before young Philip arrived at Princeton. Freneau’s widowed mother hoped he would join the clergy, but her son would show greater aptitude for writing, as both a poet and a fierce political polemicist. Rounding out the group was a member of the Class of 1772, William Bradford Jr., a printer’s son from Philadelphia who would go on to become a lawyer and attorney general of the United States under President George Washington. (One of Bradford’s classmates was the famous — and, to some, notorious — Aaron Burr Jr., a future vice president of the United States.)

The foursome shared much besides a love of learning, including a deep attachment to the patriot cause that was beginning to swell around the colonies. The focus of their political as well as literary and rhetorical exertions became the American Whig Society, founded in 1769, its name a mark of its founding members' attachment to the old principles of British political and religious dissent that were ripening into the principles of the American republic. In their battles with the rival Cliosophical Society (founded a year later, and best represented by another member of the Class of 1771, Samuel Spring), the Whigs honed their skills in political thinking, debate, and acid repartee, some of it at a level befitting college students. (“Jemmy” Madison, a shy, bookish student with a reputation for discretion, told his rival Spring on one occasion that he ought to refrain from writing poetry lest he be “transformed into an ass.”)

After Princeton, Brackenridge would become a judge and a writer, most famous for his long episodic novel, Modern Chivalry, published in several volumes between 1792 and 1815 — a work in the tradition of Tom Jones and Don Quixote set in the rude settlements of the American wilderness. Freneau’s verse would earn him the title “Poet of the Revolution,” and more serious fame as the progenitor of a distinctly American Romantic literary aesthetic. He also joined with Madison in politics as editor of the National Gazette, the first important newspaper of the emerging Jeffersonian opposition in the 1790s. Classmate Gunning Bedford Jr. helped frame the U.S. Constitution; John Black supported it at the Pennsylvania ratification convention. As for Samuel Spring, he would go on to join the Congregational ministry in New England, where, in writing and from his pulpit, he joined other New England pastors in denouncing Madison’s decision to go to war with Great Britain in 1812.

It was said that the battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton. With almost equal justice, one could say that the institutions and political controversies of the early American republic were initially rehearsed at Princeton — thanks mainly to the remarkable Class of 1771.

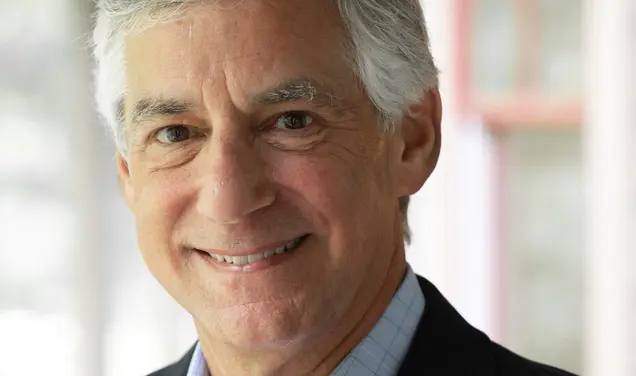

Historian Sean Wilentz is the Sidney and Ruth Lapidus Professor in the American Revolutionary Era and the author, most recently, of The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln.

No responses yet