Frederik J. Simons, Princeton professor and associate chair of the Department of Geosciences, was in Princeton’s Guyot Hall when the building started to shake at 10:25 a.m. on Friday, April 5.

Although construction has been heavy in that area of campus, he knew exactly what he was feeling.

“This was an earthquake because this was a shock that … was stronger than anything I’d ever [felt],” he said. And it “went on for 30, 40 seconds.”

Indeed a 4.8-magnitude earthquake was felt on campus — and across the region — and caused minor damage to University property.

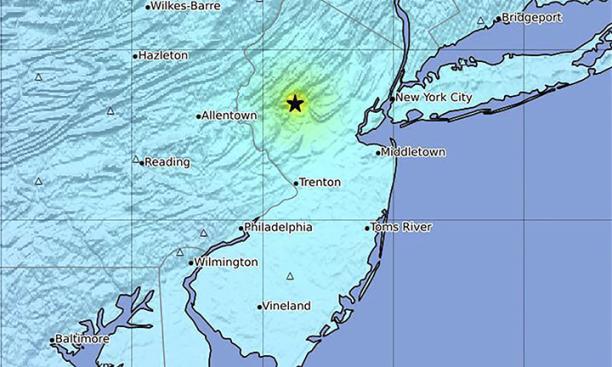

According to the United States Geological Survey, the earthquake’s epicenter was near Whitehouse Station, New Jersey, about 25 miles northwest of Princeton. News reports indicated that it could be felt as far north as Boston and as far south as Washington, D.C.

Guyot houses seismographs in the basement, and Simons said a magnitude 4 earthquake is not that uncommon in the Northeast. The region “is pretty quiet, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t regular earthquakes,” he said. “This is seismically active, it’s just not in a major way.”

A TigerAlert message sent to the campus community at 11:03 a.m. said there were “no reports of injuries or damage on campus,” and that normal activities could resume. In the moments after the earthquake, PAW observed a handrail that came loose next to the University Store by Blair Arch and talked with a student who said a window panel outside Whig Hall had fallen off.

In the afternoon, the University again emailed the community, noting there were no “reports of significant damage on the Princeton campus or other University facilities.” The message also said that Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, where nuclear fusion and plasma physics are studied, closed for the day and officials there were continuing “to evaluate the status of facilities.”

The magnitude of the earthquake “just about ties it with the largest recorded earthquake within [the state’s] borders,” according to Allan Rubin, Princeton professor of geosciences, who told PAW via email that the largest previous earthquake was a 4.8-magnitude in 1938. “But there have been only a few this large in the last 300 years.”

The state’s hazard mitigation plans over the years, including as recently as 2019, report the highest magnitude earthquake in New Jersey occurred in 1783, with a magnitude of 5.3.

Rubin said April’s earthquake occurred “on or close to the Ramapo fault, the largest … [and] most active” fault in New Jersey, which typically produces an earthquake large enough to feel every two to three years, though Rubin added that those earthquakes are usually only magnitude 2 or 3.

Simons, who fielded news media requests the rest of the day, encourages interest in earthquakes because “science needs careful, long-term sustainable support and curation.” He said geosciences faculty and students at Princeton will be studying the data for days, possibly weeks, and “if an undergraduate wants to see some of that,” Simons will happily entertain visits to Guyot Hall.