July 9, 1931 – Sept. 26, 2015

In the early 1960s, Princeton’s admission office was facing what its director called a “college panic.” Baby boomers were applying in large numbers — there were far more qualified applicants than could be admitted. Officials sought to admit more talented black and public-school students, and to push back against Princeton’s country-club image in order to lure the very top students away from Harvard and Yale. Alumni were up in arms, worrying that their sons’ chances to attend Princeton were dwindling.

In 1962, the director of 17 years, C. William Edwards ’36, resigned. In his place, Princeton hired E. Alden Dunham ’53.

Fresh out of Columbia University’s Teachers College and not yet 31 years old, Dunham was determined to expand the applicant pool and ensure that young men offered admission to Princeton had earned that privilege. He focused more on admitting the “well-rounded class” than the “well-rounded boy.”

“He knew [recruiting African American students] was controversial, and he was bright enough and strong enough to deal with the controversy.”

Jim Wickenden ’61, assistant director of admission from 1963 to 1967

Dunham “decided that we should aggressively recruit young African Americans,” says Jim Wickenden ’61, assistant director of admission from 1963 to 1967. “He knew it was controversial, and he was bright enough and strong enough to deal with the controversy.”

Though the numbers look small in retrospect, Dunham’s efforts succeeded: In his first year, only five African Americans matriculated, but by the time he left in 1966, 18 black students were entering Princeton. Young men from underrepresented states and rural areas were recruited, too. Meanwhile, the percentage of alumni sons accepted dropped from 59 percent in 1964 to 47 percent two years later.

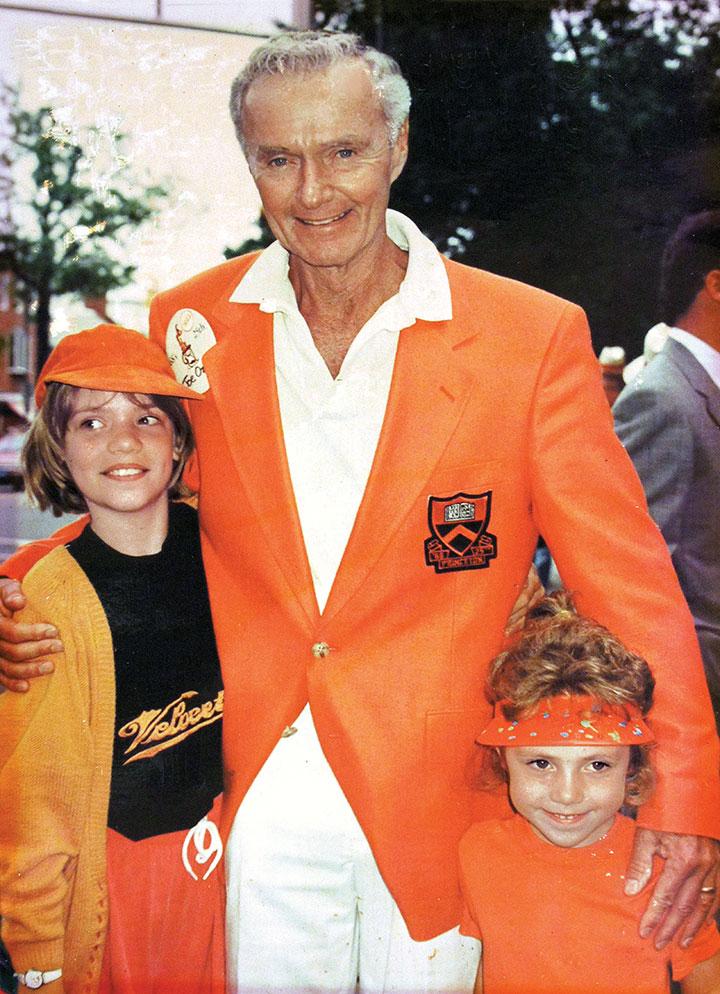

Dunham’s daughter, Ellen Dunham-Jones ’80 *83, recalls that her dad sometimes would be called to Nassau Hall to explain his decisions. When President Robert Goheen ’40 *48, who went on to open Princeton’s doors to women, asked the director why he had turned down a prep-school boy whose letters of recommendation had come from powerful people, Dunham replied that “it was his experience that ‘often, when the big guns are called in, it’s because the little gun doesn’t have any ammunition,’” she says.

Perhaps the best-known student to win acceptance during Dunham’s tenure was Joseph D. Oznot, a high school senior who was admitted into the Class of 1968.The New York Times soon reported that Princeton had accepted a student who did not exist. Four members of the Class of 1966, along with accomplices, had fabricated a personal history (Oznot’s birthdate: April 1) and high school transcript, taken the College Board exams in his name, and even sat for an interview.

“The headlines — I’ll never forget this — said ‘Oznot Is Not,’” Wickenden says. “Alden handled it well; he thought it was a terrific hoax.”

After Princeton, Dunham worked for the remainder of his career as an officer at the Carnegie Corp., where he continued to play a major role in expanding opportunities in American higher education. He preferred the company of farmers and plumbers to New York City advertising types, his daughter says.

“He wanted to make sure that my siblings and I didn’t grow up as Princeton kids, with the expectation that everybody is ... well-educated and has all these opportunities,” Dunham-Jones says. “[He made sure] we had a chance to meet and learn to love people who had a lousy education and limited opportunities, but were wonderful and smart people. He always wanted us to be aware of that.”

Allie Wenner is a writer and memorials editor at PAW.