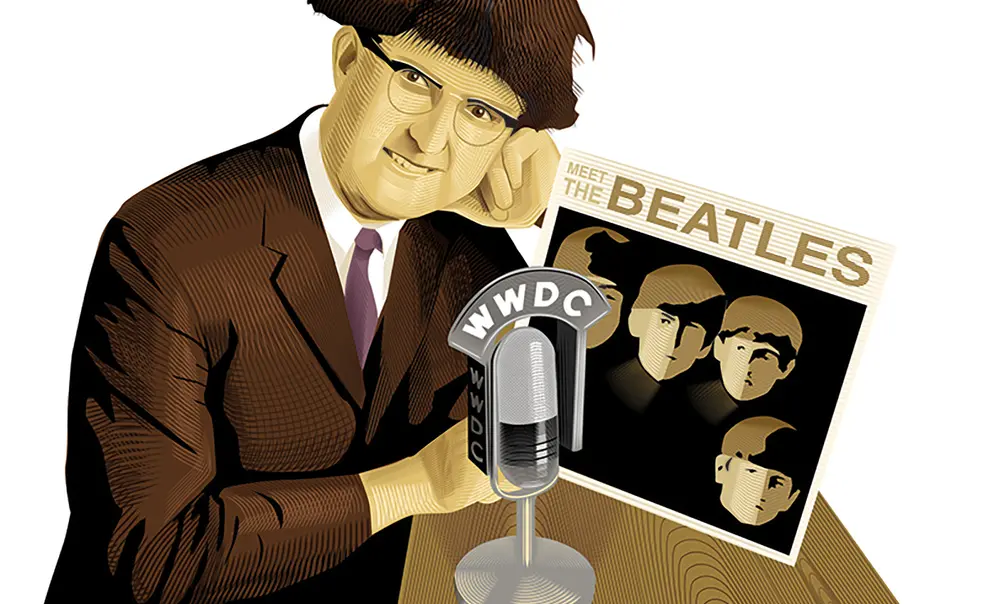

How CJ the DJ Gave the Beatles Their Big Break in America

Princeton Portrait: Carroll James ’58 (1937-1997)

On Dec. 17, 1963, Carroll James ’58, a disc jockey who spun records on WWDC in Washington, D.C., put a record on the air at the request of one of his listeners. Marsha Albert, a 15-year-old girl in Silver Spring, Maryland, had written to the station to ask to hear a band she’d seen in a short television clip but hadn’t heard anywhere on the radio. James gamely ordered a copy of its latest record from overseas; the band, a little English outfit, was popular across the pond but hadn’t broken through to the United States.

James invited Albert to the studio, where she made a guest appearance on his program to introduce the song. Then American listeners, for the first time, heard the Beatles sing “I Want to Hold Your Hand.”

That was the official start of Beatlemania on the American scene. After the show, so many listeners called to ask for the song to be played again that the station’s switchboard fritzed out. Astonished, James shared a tape of the Dec. 17 broadcast with a fellow DJ in Chicago, who played it and immediately got the same response. Soon, radio stations all over the U.S., unable to quickly get copies of the Beatles record themselves, were playing the tape of the broadcast. In response to the hubbub, Capitol Records, the label that had acquired the U.S. rights to “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” released the record more than a month ahead of schedule. Then The Ed Sullivan Show came calling.

The Beatles were grateful to James for the breakthrough. In February 1964, just before they played a concert at the Washington Coliseum for 2,000 screaming fans, they dropped by a WWDC broadcast trailer to chat with him on the air.

After the show, so many listeners called to ask for the song to be played again that the station’s switchboard fritzed out.

“John, they call you the chief Beatle,” James said to John Lennon.

“Look, I don’t call you names,” Lennon retorted. “Don’t you call me names.”

“Well, who’s responsible for the haircut?”

“Well, I think it’s bigger than both of us, Carroll. That’s all I can say.”

Then George Harrison told a story about visiting the U.S. in October 1963, just a few months before James’ broadcast: “In New York, I went into a record shop to ask if they’d ever heard of us, and they hadn’t.”

Near the end of the interview, James brought out Albert to meet her idols. The Beatles greeted her warmly: “All right, Marsha!” “Hullo, Marsha!” “Good old Marsha!”

James got his start in radio at Princeton, where he was, in the words of Harold Pachios ’59, “an extraordinarily popular student disc jockey on WPRB.” During the same years, he spun tracks, using the handle “CJ the DJ,” for local radio stations in Trenton and New Brunswick. He had a reputation for irreverent wit, which made him an appropriate ambassador for the Fab Four.

What made the Beatles break through? Their previous lack of success in the States wasn’t for lack of trying. Years later, Harrison’s sister, Louise Caldwell, told James that, after she moved to Illinois from England in 1963, she wrote “countless letters” to American radio stations and drove “countless miles” to give DJs copies of the Beatles’ record — copies that presumably went straight in the trash. “I just wish that I could have found one DJ in the Midwest with your ‘drive,’” she wrote to James.

Clearly, once they got a chance, their talent spoke for itself. But they owed that chance to a DJ with an adventurous ear and a love for his listeners, together with a young girl who understood, after hearing one guitar riff, what the industry’s gatekeepers didn’t.

For the rest of his career, James had the nickname, “The Man Who Broke the Beatles.”

2 Responses

Martha James Nichols

1 Month AgoAn Endorsement from Walter Cronkite

As the younger sister of Carroll S. James Jr., l can relate that his radio career started as a child with a pretend station in the basement of our home. His first show on the air began when he was 15 and convinced a manager of WJEJ in Hagerstown, Maryland, that a high school program was needed on Saturdays. Carroll loved working to fill in for regular staff when they needed time off. When he was a junior in high school, a friend of our Aunt Virginia James, Walter Cronkite, tested Carroll for several hours one Saturday and told our parents that Carroll already had a developed voice and style. He encouraged going to Princeton for a solid education — and the rest is history!

James Russell Stevens ’76

3 Months AgoStudying the Beatles’ Rise in the U.S.

In 1976, my senior thesis was on a similar subject; however, the sociology department assigned no thesis adviser. The final result fell short of my expectations.