Four and a half minutes into Caroline Shaw’s “Passacaglia,” the eight singers in the vocal ensemble Roomful of Teeth dissolved into cacophony, blurting out an unintelligible babble of spoken words. After passages of plainsong, delicate Appalachian-style harmonies, and even a bit of Tuvan throat singing — the sort of mashup that would lead one reviewer to liken the group to “a glee club on molly” — her work seemed to have gone off track. The audience in the summer of 2009 at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art in North Adams, at the base of the Berkshires, could only have wondered what was going on.

Shaw did this by design; she hoped to hear a jumble of people talking over one another. She wanted that talk to break down into simple, childlike vowels, then a guttural vocal fry, before surging a split second later into a booming, glorious chord. In rehearsals, Shaw worked with members of the ensemble — of which she is a founding member — to perfect the sound she desired.

“Where you know who’s playing it,” she says, “you create the music somewhat together. You don’t have to tell them exactly how to do it. I like that, I like the idea of a musical community and the human community that suggests.”

In that moment, when Roomful of Teeth soared into a D-major chord, Shaw brought order from aural chaos and knocked listeners back in their seats. “Passacaglia” was a late addition to the program, written in just 10 days when the group’s director, Brad Wells, needed more repertoire and invited his singers to contribute something. Shaw, a trained violinist and singer but hardly yet a composer, had taken him up on the offer.

Wells vividly recalls that first performance. At the climactic chord, the audience erupted with whoops and cheers before the group brought Shaw’s composition to a close. It is something, he says, that he has not seen before or since.

Over succeeding summers, Shaw wrote three more movements, which she collectively titled Partita for 8 Voices. (A partita is a Baroque dance suite; the movements, “Allemande,” “Sarabande,” “Courante,” and “Passacaglia,” are also names of renaissance or baroque dances.) In 2013, she submitted Partita for the Pulitzer Prize, reasoning that the $50 filing fee was cheap and that someone on the selection committee might help Roomful of Teeth get a gig. To the surprise of nearly everyone in the music world, it won, making Shaw, at age 30, the youngest person ever to win the music Pulitzer, and one of only a few women. (Julia Wolfe *12 won in 2015 as an oratorio for Anthracite Fields, which traces the history of coal miners in central Pennsylvania.) This March, The New York Times listed Partita among its “25 Songs That Tell Us Where Music Is Going.”

Shaw herself is going everywhere, spending much of the last few years living out of a suitcase. She has collaborated with hip-hop artist Kanye West on his new album, played violin behind Paul McCartney on Saturday Night Live, had compositions performed from Vancouver to Cincinnati, and is currently backlogged with commissions. Her latest work, one of seven responses to Dieterich Buxtehude’s 17th-century sacred masterpiece, “Membra Jesu Nostri,” will premiere June 24 at the Episcopal Cathedral in Philadelphia, part of a two-night concert performed by the chamber choir The Crossing.

Any article for this magazine about someone so accomplished usually would have a class year appended to the person’s name. Caroline Shaw, however, lacks such an appellation: She is still a Ph.D. student in Princeton’s graduate music-composition program.

Her selection represented a dramatic departure for the Pulitzer selection committee. Historically, the music prize has been something of a lifetime-achievement award, given to composers late in their careers (such as the late Princeton professor Milton Babbitt *92, who won in 1982, when he was 65) in recognition of a body of work. By selecting Shaw, the committee turned to an emerging composer, praising Partita as a “highly polished and inventive a cappella work uniquely embracing speech, whispers, sighs, murmurs, wordless melodies, and novel vocal effects.”

“Fresh” is the word often used to describe Shaw and her work; freckled and soft-spoken, she looks even younger than her age. But she is unafraid to dive into unconventional musical techniques (her percussion piece “Taxidermy,” for example, is written to be played on flower pots) and is in the forefront of a movement that is blurring the line between composer and performer. Shaw occupies both worlds comfortably. We are only beginning to see where it will take her.

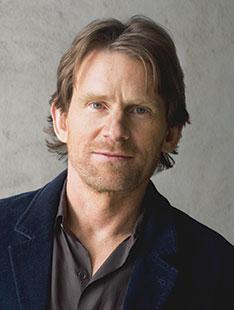

“I like the idea of a musical community and the human community that suggests.”

Caroline Shaw

When Shaw applied to the graduate music program in 2010, she had “Passacaglia” but precious few other works in her folder. Though she was an accomplished singer with a master’s degree in violin performance from Yale, her acceptance to Princeton’s program — which receives as many as 140 applications each year for four spots — was hardly guaranteed. What convinced the department to take a chance on her as a composer?

“She had a small portfolio but it was incredibly unusual — unlike anything else that was in the pile that year or really any other year,” says Professor Dan Trueman, who is now Shaw’s adviser. Her proficiency as a violinist and singer alone set her apart. “There was this sense of a really accomplished musician who wasn’t imprisoned by the notion of her being a performer. As a result, it felt extraordinarily fresh and different. It felt outside the box.”

Shaw was raised in Greenville, N.C., the great-great-granddaughter and niece of the famous 19th-century conjoined twins, Chang and Eng Bunker. Her mother began to give her violin lessons when she was 2, the same time she was learning to speak, forging a lifelong association between words and music. Never shy about copying musicians she liked, she listened to La Traviata every night before she went to bed when she was 10, then tried to emulate the soprano’s vibrato on her violin — in other words, to make the instrument sound like a singer. Listening to Mozart inspired her to write her first string quartet at the age of 9, in G major, but she indicated all the F-sharps individually because she did not yet understand the musician’s shortcut of marking them in the key signature.

She studied violin at Rice University, dabbling in more mainstream popular music with some catching up to do. (Shaw says that when her a cappella group began rehearsing the Madonna hit “Like a Prayer,” she had never heard it.) Even as she perfected her violin technique in graduate school at Yale, Shaw was becoming more interested in singing. She joined the choir at a New Haven Episcopal church and recalls weeping at the stark beauty of candlelit Tenebrae services. To earn extra money, she played as a piano, violin, and percussion accompanist for dance classes at a nearby high school.

With that on her résumé, and a quarter of what would become Partita written, she applied to Princeton.

Shaw says she had long wanted to write music but had avoided taking composition lessons because she feared that she would be too faithful in following directions — a useful skill for learning the violin, but stultifying in more open-ended creative endeavors. Princeton’s program, which emphasizes experimentation over instruction, proved tailor-made for her.

Graduate students take two seminars per semester during their first two years, but there is no fixed curriculum. Professor Steven Mackey, the department chair, says the department rejects the idea that composers can be built using a formula. “You’ve got to be driven from within, and we’ll facilitate that,” he says. “We don’t have all these requirements: ‘If you do this, this, this, and this, you’ll be a great composer.’ It doesn’t work like that.” Adds Trueman: “They all need to learn something, but we don’t know what that is.”

As much as possible, the program encourages budding composers to learn from each other in spaces such as the Princeton Sound Kitchen (formerly the Composers Ensemble of Princeton), which provides a performance venue for graduate students and music faculty to share their work. For their general examination, taken at the end of the second year, composition students are asked to write something that responds to a composer whose style is unlike their own. Shaw chose Chopin, whose Opus 17 A-minor Mazurka contains chromatic harmonies very different from the simple triads she preferred. Comparing Chopin’s piece to prosciutto and mint, a delicious blending of flavors, Shaw likens her response, titled “Gustave Le Gray,” to Japanese sashimi. “That is,” she explains on her website, “it’s often made of chords and sequences presented in their raw, naked, preciously unadorned state — vividly fresh and new, yet utterly familiar.”

When she finished her course work in 2012, Shaw moved to New York and continued to sing with several New York-based groups, most notably the renowned church choir at Trinity Wall Street and Roomful of Teeth.

Wells, a professor at Williams College, founded Roomful of Teeth to explore new musical styles and techniques; the ensemble performs near the college during the summer. At their first rehearsals in the summer of 2009, Wells introduced the singers to yodeling and Inuit breathing games, bringing in an expert from Tuva (a region in southeastern Russia) to teach throat singing and reassure nervous singers that the weird guttural sounds wouldn’t harm their voices. Shaw took to the challenges immediately, her mind brimming with ideas. The ensemble would rehearse all day. Then, Shaw would go to Williams and play the piano until 3 or 4 a.m., writing new music that she would share with Wells the next day.

After the positive reaction to “Passacaglia,” Shaw wrote three more movements over the next three summers, drawing on sources from around the world and across the ages. Some sections were inspired by Bach’s partita takeoffs. Others have singers reciting lines from artist Sol Lewitt’s “Wall Drawing: 305,” which hung in the North Adams museum where the ensemble performed and describes the location of 100 points on the wall. She analogizes the cacophony in “Passacaglia” to the babble of information when surfing the Internet.

Her finished Partita appeared on Roomful of Teeth’s debut album in October 2012; the album won a Grammy Award and became the best-selling piece on the iTunes classical charts. After the group first performed it live at (Le) Poisson Rouge in New York, reviewer Justin Davidson gushed that Shaw “has discovered a lode of the rarest commodity in contemporary music: joy.” On a warm spring day five months later, in March 2013, Shaw was walking along the Hudson River when her phone began buzzing and she learned that she had won the Pulitzer Prize.

Donald Nally, the chair of the graduate music department at Northwestern University, who commissioned Shaw’s newest work for his Philadelphia-based choir, The Crossing, lists her among a group of modern composers who are comfortable blending musical styles.

“It’s diminishing the rather severe boundaries between popular music and so-called classical music that were drawn really strongly throughout the 20th century,” he explains. “It’s a beautiful thing because it speaks very immediately to people.” Nally distinguishes these new artists, including Wolfe and Judd Greenstein *14, from late 20th- and early 21st-century composers such as Brian Ferneyhough and Helmut Lachenmann, whose rigid and highly intellectual scores almost celebrated their inaccessibility.

Notations in Shaw’s work, always spare, are helpful, even gentle. “Passacaglia,” for example, includes the following: “Each bar should last about four seconds and can be cued by either a conductor or just by the musicians themselves. ... The spacing of pitches throughout the bar, for each part, is approximate. Don’t feel too tethered to it, but maybe use it as a guideline.”

This light touch “flies in the face of the belief that every little intonation has to be set down, which is absolutely wonderful,” Trueman says. “But that does fly in the face of conventional values for composers: ‘Oh, look at the score, and see every detail and make sure that every dynamic marking is explicitly articulated so musicians a hundred years from now can know how to interpret it.’ It takes a certain level of bravery and confidence not to be drawn into that.”

It also opens new musical possibilities. “Partita,” Mackey says, “has things you could only do if you were in the trenches working with this singing group.” Shaw has had to make accommodations when writing for large orchestras, however, as rehearsal time is expensive and hard to come by. “Lo,” a concerto she wrote for the Cincinnati Symphony, contains more precise notations except for a violin solo that Shaw played, and largely improvised, when the piece was performed earlier this year.

Shaw’s boldness in blending and borrowing styles can be heard in her new composition for The Crossing. Buxtehude’s work is a series of seven cantatas, each describing a portion of the suffering Christ’s body. Nally invited her to respond to the section that describes the hands, thinking that her nimble hands as a violinist might help her relate to it.

Shaw takes Buxtehude’s text, which describes the wounds of the crucifixion, and reimagines it to include hands metaphorically opened to welcome refugees. She weaves passages from the original Latin with snippets from Emma Lazarus’ poem “The New Colossus,” which adorns the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty.

Asked how she conceives a 21st-century response to a piece of music written in 1680, Shaw replies, “I think of it as sort of an age-old recipe. You have this beautiful old recipe for meatloaf that your great-grandmother made. I’m not trying to reinvent that meatloaf, but you can combine it with something else that makes a different kind of meal. Maybe you won’t even notice that the meatloaf is part of it anymore, but the concept of that meatloaf is in it.”

The years since Shaw won the Pulitzer have been dizzying. Kanye West heard her at a Democratic fundraiser in May 2015 and went backstage to meet her. After pulling out his phone and sharing some new material, he suggested that they work together. Shaw wrote and sings backup on a few songs on his new album, but is circumspect in talking about the experience. “He has very different personas. I really love his thoughtful, quiet artist place,” she says. Nevertheless, “We’re just in really different worlds.”

The final stage in any doctoral program, of course, is writing a dissertation. Shaw hasn’t begun hers yet — she has been busy. Still, with a Pulitzer Prize and national acclaim to her credit, one might ask if she needs a Ph.D. Shaw insists that she will write her dissertation, but hasn’t settled on a topic.

“Princeton gave me the opportunity to do their program and I’d like to finish it,” she says. “I’m not a quick writer of words; I’m a quick writer of music. But every time I’ve written a paper or an essay in college or grad school, it has taught me a lot.”

Besides, she adds, “My grandmother would also be really disappointed if I didn’t finish. She mentions it every time.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.