This September, Adam Hudnut-Beumler ’17 made his debut in the Triangle Club’s storied all-male drag kickline. The experience, he says, was a highlight of his theatrical career: “It was a joy and a thrill.” But while his performance looked footloose and fancy-free, getting to that point wasn’t simple.

First, Hudnut-Beumler had to decide whether to participate in the kickline at all. “There’ve been people in the past who’ve opted not to do the kickline because they have that opinion that it’s making fun of the feminine form,” Hudnut-Beumler explains. “Plus, there’s the idea that the best choreography is still going to the men rather than the women — it’s about the propagation of a patriarchal structure of doing the most important number as the men’s number.” He ultimately chose to enter the fray for Triangle’s Freshman Orientation Week show: “I see it as a tradition thing.”

Then there was the not-insignificant matter of learning the kickline’s intricate choreography: a routine filled with parasol twirls, folly walks, and synchronized high kicks — all performed, of course, while wearing neon-orange high heels. Fortunately, Hudnut-Beumler had that covered. “I actually like the heels,” he says, after his first fully shod rehearsal. “I have really big calves, so I think that might be part of it; they take some of the weight off my feet.”

Finally, Hudnut-Beumler faced the very modern question of cultural appropriation. For the Freshman Orientation show, the club was reprising “We Call the Shots,” a song that dressed kickliners as tropical drinks and had them deliver saucy come-ons. Hudnut-Beumler was inheriting the role of “Piña Colada” from a departing alumnus named Manny. Manny, Adam says, had delivered the line “Piña Colada so strong / she’ll put you in a Singapore Sling!” in a funny Hispanic accent. “But Manny’s also Manuel Marichal [’16]” — that is, a Hispanic person — “and I’m Adam Hudnut-Beumler, so there’s a different feeling.” He dropped the accent.

What’s so funny about a man in a dress? It’s an increasingly fraught question — one that Triangle members are debating as they celebrate the club’s 125th anniversary this year. “The kickline is this thing that is so emblematic and encapsulates so much of Triangle,” says former Triangle actor and writer and current playwright Sean Drohan ’14. “The tradition, the revolution, the subversiveness, the establishment, the pageantry, the artistry.” Talk to even the oldest Triangle alums, and they still tell you the glorious details of their first kickline: the steps, the costumes, the rush of adrenaline, the wild applause. Performing in Triangle shows has introduced Princetonians to their future spouses, helped launch the performing-arts careers of alumni like Jimmy Stewart ’32 and Ellie Kemper ’02, and provided countless Tigers with a family-like support system on campus. The kickline has been at the heart of this enterprise for almost as long as Triangle’s been in business.

And yet, it must be asked — and has been asked, by current students and alumni alike: Might Triangle’s tradition of bawdy female impersonation be insulting to women? “We’ve had a trend in the past 10 years where the kickline’s lyrics have been centered thematically around insatiable female lust,” says Kendall Crolius ’76, one of Triangle’s earliest female crew members and the club’s first female alumni board chair. “It’s kind of hard to break the pattern.” What’s more, in an era of greater LGBT visibility, might the use of cross-dressing as a visual punch line demean the struggles faced by transgender students and other queer Princetonians? These are the questions that Triangle members have been hashing out over the past several years: in writers’ workshops, in dressing rooms, and in conversations with alumni board members — and most especially, in a special undergraduate town hall meeting that convened last year to ponder the future of the kickline. That discussion is still underway.

TALK BACK Triangle’s kickline brings the house down — but is it time to rethink it?

Princeton’s historic musical-comedy institution has the privilege of marking its quasquicentennial at a time when comedy, historic institutions, and the concept of “privilege” are under scrutiny. Accordingly, Triangle Club has recently made a number of changes in the spirit of sensitivity and inclusion. Three years ago, the club altered a tradition of awarding “tour scarves” to students who hooked up on tour, after it made students uncomfortable. The previous fall, the club had ditched a plan to outfit its mostly white cast in Afro wigs (for a funk number) after a Triangle member raised concerns about racial insensitivity. And this September, the club dropped a pro-Woodrow Wilson number from its Freshman Week show (“So great! First rate! The famous Woodrow Wilson!”) in the wake of student protests against Wilson’s racial policies.

There are no plans to drop the kickline from Triangle’s upcoming anniversary celebration Nov. 18–20: a weekend featuring the debut of a new, ancient-Greece-themed Triangle show; a “sketch slam” for old and new Triangle writers; and a memorial service to “honor friends who have joined the Great Kickline in the Sky.” (The event is expected to be the largest-ever gathering of Triangle alumni.) The kickline is too central to Triangle’s identity, and too beloved by generations of Princetonians. But talk to Trianglers past and present about what the kickline will look like in the coming decades, and you get a range of answers:

“I hope we always have it. It’s a real crowd-pleaser and always a highlight of the show.” (Kendall Crolius ’76)

“I feel like it’s only a matter of time until there’s going to be a year when the kickline as we have known it doesn’t happen. Just because feelings are too strong about what it means for men to dress up as women and have that be funny.” (Pete Mills ’95, Triangle alum and the club’s current music supervisor)

“Um ... [pause] I think that there will always be a kickline. What that kickline looks like is going to be up to future officers of this club. If in 25 years the kickline’s coed ... hooray. I don’t feel very strongly about it being an all-male enterprise.” (Hillel Friedman ’17, current Triangle president)

Fortunately for Triangle, if there’s one benefit of turning 125, it’s that there are no new problems under the sun. A look at the club’s history, and specifically its tradition of female impersonation, reveals an ongoing push and pull between tradition and innovation, propriety and subversion, in which this latest debate over the kickline is but one new wrinkle. Triangle is “the country’s oldest touring collegiate musical comedy troupe,” but it’s also an institution that essentially creates itself anew each year with a fresh batch of student-written numbers. Triangle’s task has always been to change with the times while maintaining its essential traditions — and to make that change look as smooth as a synchronized high-step.

What’s so funny about a man in a dress? In the beginning, nothing at all. In the earliest days of Triangle, cross-dressing was simply a matter of necessity at an all-male college — part of a long tradition of female impersonation tracing back through ancient Greece and Shakespeare’s Globe. What was most subversive about Triangle’s first performances in 1891 was not that Princeton men were playing women, but that they were acting in plays at all. Since its founding in 1746 as a school that would train Presbyterian ministers and others sympathetic to the Great Awakening, Princeton’s culture had been hostile toward the theatrical arts. “We hope to abolish the theater just as much as other vices,” Princeton’s future president, John Witherspoon, wrote in 1757 — an attitude the administration upheld well into the 1800s.

The first Triangle theatricals were relatively serious in nature. But as the club found its footing, it began to borrow more and more humor from the vaudeville entertainments of the day. While some of Triangle’s female roles, like the ingenues portrayed by the likes of F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917, were played straight, other women characters had names like “Hot Airy Mary” and were presented for laughs.

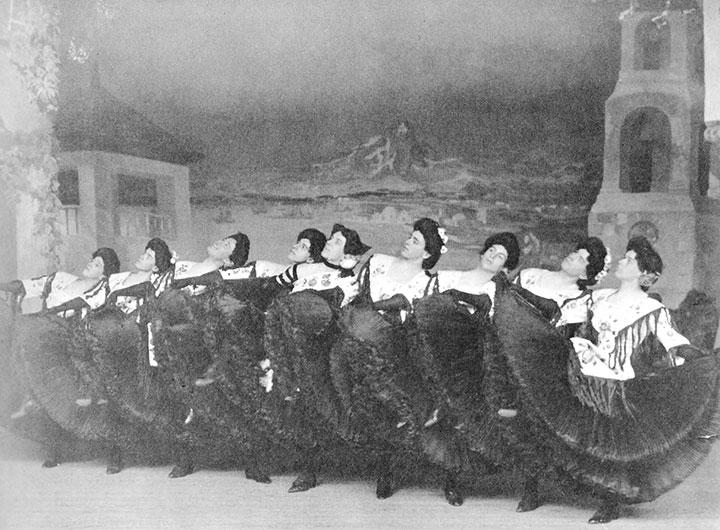

The first Triangle kickline appeared in the 1905 musical Tabasco Land, and represented Princeton’s take on a popular type of dance performance called a Pony Ballet — in which showgirls linked together to imitate show horses’ synchronized kicks and high steps. According to Triangle historian Donald Marsden ’64 in his book The Long Kickline, the main goal of these early kicklines was to create a visual spectacle. Comedy came later, as Triangle fully embraced vaudeville raunch and razzmatazz in the later decades of the 20th century.

As early as the 1900s, however, Triangle’s shows included jibes about the dirty thrill of dime novels and the need for a Pure Food and Drug Act (“The meatpacking houses are all on the pork, insurance is full of debris / the ice in our ice coolers, is not what it’s cracked up to be”). Later on, the club’s penchant for satire and sight gags took on the mantle of a youthful birthright. The Triangle Club “is the great vitrine for youth, the bulletin board for young ideas, the proving ground for talent that is still permitted to fumble; it is a place to sing, to do pratfalls, to thumb one’s nose at authority, to test the last liberties of adolescence, to taste the true wine of being an American,” recalled Joshua Logan ’31, the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer and director, in the foreword to The Long Kickline. Princeton itself was not spared appraisal under Triangle’s gimlet eye: Logan’s 1930 song “McCosh Walk,” for instance, took aim at the falseness of Bicker Week.

Wet guys who know you, don’t recognize

But say “hello” to important guys.

Mind who you’ve been seen with, been seen with

Along the McCosh Walk.

The kickline — and other acts with men dressed as women — became a way for students to poke some fun at campus traditions and, in a limited way, at traditional gender norms. As early as 1908, PAW applauded the faculty for cutting back on the club’s out-of-town trips, declaring: “Certainly [such an act] does not leave with the audience an impression of that manly quality they like to ascribe to our students, a quality developed by sound minds in sound bodies.” The fear was that dancing in drag could turn Princetonians womanly, decadent, or perhaps even homosexual. In 1915, one alumnus recalled, a Princeton professor “lectured us for about an hour on the evil philosophy of Oscar Wilde and others of that ilk” following Triangle’s performance of a particularly rowdy kickline.

Vaudeville lent Triangle its bawdy edge; unfortunately, the club also borrowed from the popular stage a penchant for vile ethnic humor. Blackface was a feature of Triangle shows as recently as 1948’s All in Favor, whose plot hinged on rival politicians fighting for the endorsement of a minstrel show. Other lowlights from the Triangle’s early catalog include “Minnie Ha Ha,” a red-face number performed by Joshua Logan and Jimmy Stewart, and 1913’s “Chinee Laundry Boy” (“For dirtee don’t you caree / Your clothes we never tearee/ Take ’em to a Chinee laundry boy”). The club’s portrayals of lower-class women could be crude, if not outright offensive.

The show’s comic outlook most frequently reflected the perspective of privileged young men, which Triangle’s members largely were. What a Relief!, in 1935, presented a takedown of the New Deal as transposed into Ancient Rome. (FDR/Jupiter: “I intend to keep my promise to put this government out of the black and into the red!”) When Triangle took its shows on the road, its cast members toured the country’s moneyed enclaves in Pullman sleeper cars, mixing with eligible young women at debutante balls and society teas along the way. As befitting its establishment nature, the club also enjoyed audiences with Presidents Teddy Roosevelt, Taft, Wilson, and Eisenhower.

It took the cultural upheavals of the late 1960s for the club to shake its conservative bent. In the space of only two years, and with the full support of its alumni board, the club integrated racially and welcomed women. (It’s worth noting that Triangle’s comedic counterparts, the Hasty Pudding Club at Harvard and the Mask & Wig Club at Penn, have never extended a similar welcome to women.) “Triangle has been ahead of the rest of Princeton in all cases. And that goes back to the 1950s and the history of Jewish integration,” says Crolius, though she adds that the club still needs to do a better job of attracting a racially diverse cast.

Call a Spade a Shovel — the first Triangle show to feature a fully integrated cast — also featured stark sets, a rock ’n’ roll score, and a willfully offensive anti-Vietnam War message. The show’s tour was a financial disaster. In conservative Grosse Pointe, Mich., more than 300 audience members walked out before curtain call. “It wasn’t even humorous. The message was just ‘Screw you!’” Which was how all of us felt, of course,” recalls Shovel veteran Geoff Grubbs ’72.

What followed was a decade of experimentation and soul-searching. “The club was forced to look very carefully at, OK, what are we now? ... Triangle had to find its identity. And it had to find its real heart,” recalls Marc Segan ’77, now the chair of Triangle’s alumni board.

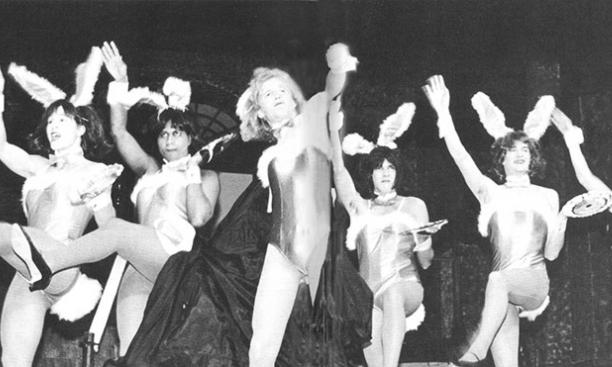

During this time, the kickline changed from being one of the more provocative elements of a conservative institution to being a traditional holdover embedded within a more progressive club. The club experimented with all forms of kicklines: gender-swapped kicklines in which the men played women and women played men; agender kicklines in which participants dressed as cockroaches and gorillas; even a blacklight kickline in which it was hard to see much dancing whatsoever. Eventually, though, the club’s leadership realized that the old way of doing things — a bunch of young men dressed as young women — was what reliably brought down the house.

“We had the conversation of, you know, could we do a women’s kickline where they’re all dressed up like men. And it’s interesting: not funny!” Crolius recalls. “And there’s all kinds of weird sociological theories about why both men and women find it threatening to see women in a position of power. Men in a dress and high heels: funny. Women dressed like macho men: not funny.”

In the 1980s and ’90s, the club solidified what would become its modern house style — just in time to capitalize on a wave of attention that followed new cast member Brooke Shields ’87. Besides featuring an all-male kickline, modern Triangle productions aspired to be punny, quippy, and book-smart, as reflected in show titles like Satanic Nurses and Rhyme & Punishment. There could be a smattering of topicality — Cold War jokes in the ’80s, George W. Bush jibes in the 2000s — but not so much as to risk another Call a Spade a Shovel situation.

From time to time, the kickline came in for criticism from female cast members. They would “express disappointment and frustration at being left out of the show’s high point,” wrote Nancy Seligson Barnes ’91 in her senior thesis about the club, “One Hundred Years and Still Kicking.” Their complaints were bolstered by the rise of academic feminism that cast a critical eye on drag of all types. One line of thinking held that men dressing as women was only funny because it read to audiences as a kind of debasement. “Even on the vaudeville stages, female impersonators were usually comics who both belittled women and set standards for their dress and behavior,” wrote a feminist scholar in 1985. “[W]omen are non-existent in drag performance, but woman-as-myth, as a cultural, ideological object, is constructed in an agreed-upon exchange between the male performer and the usually male spectator. Male drag mirrors women’s socially constructed roles.”

That scholar was Jill Dolan, who is now Princeton’s dean of the college. She expanded upon these thoughts recently in an email to PAW: “The Triangle kickline now seems to me to be quoting a history of Triangle kicklines, more than anything else. That is, when it was first instituted, the drag kickline referred to women’s absence at Princeton (and perhaps derided them a bit in the way my original article suggested). ... Now, the kickline is self-referential; something expected in Triangle shows because it’s always been in Triangle shows.”

What’s so funny about a man in a dress? “I honestly can’t tell you what it’s about,” says Claire Ashmead ’17, one of Triangle’s two current head writers. “I’ve thought a lot about what the joke is, and I cannot say for sure. ... One of the criticisms is the reason it’s funny is that men can’t actually be women, so it’s making fun of the trans community. I don’t think that’s what’s going on with it.” Ashmead is offering her thoughts on the kickline during a break from one of the first read-throughs of the anniversary show: “I just think it’s so fun. ... The Rockettes don’t really do it for me. The kickline is sort of like the Rockettes, but for me. And I guess that I see it as very celebratory.

“It’s kind of burlesque, right? I’m still not sure what the kickline is. I guess you should always interrogate what things are. But I think that sometimes [it’s OK] to celebrate something you don’t fully understand onstage, when most people don’t walk away from it unhappy. As a woman, I’ve never walked away from the kickline feeling my womanhood has been offended. I’ve always been quite gleeful.”

That’s not to say that many in Triangle don’t see the kickline as ripe for an overhaul. As Ashmead’s co-head writer, Allison Light ’18, points out, “There have been questionable kicklines in the past.”

That’s perhaps an understatement. As one alumni trustee put it: “There’s been a tendency since perhaps the late ’90s with the women in the kickline where their appetites have, say, increased. They’ve become a lustier bunch than they used to be.” Crolius agrees: “We got into a phase where the kickline lyrics were always focused on insatiable sexual appetite. That is not a Triangle tradition. ... I had an undergraduate saying to me, ‘I don’t want to be in the kickline, I have a younger sister, and I don’t want her to see me sing those lyrics.’ And I thought, whoa.”

There’s also the question of how the kickline interacts with greater queer visibility on campus. “In 2016, gender impersonation and performance is much more complex, culturally and politically,” with transgender and “genderqueer” students in Princeton classrooms, Dolan writes. “The Triangle kickline seems a reminder of days when gender truly was binary: male and female and nothing in between or outside that dyad.”

As is tradition, the conceit of this year’s Ancient Greek kickline is being kept under wraps until the premiere. But the aim, the writers say, is to celebrate the dancing ladies’ strength as well as their charms. Across the show as a whole, Light says, “we really focused on creating complex female characters, perhaps at the expense of male characters.”

In addition to presenting a less sexualized kickline, the writers gave the show a female hero and villain. After a September read-through, the writers tinkered with a pivotal scene so that their heroine focused less on her boyfriend’s needs and more on her own hopes and dreams. Many of the male characters in the show are doofuses, a characterization that neither writing coordinator would dispute. “I was like, this is progress! The men are one-dimensional!” says Light, laughing.

Also progress: “We have more women than men in the writers’ room for the first time ever; we have two female writing coordinators for the first time ever,” Light says. “We have a female director. So I think we can be proud of that.” Officers say they are committed to maintaining a similar balance moving forward. The hope is that a more inclusive creative process will create a more inclusive show — and, by extension, a more inclusive kickline.

“Comedy is intrinsically dangerous,” Light says. But, she adds: “I think the lyrics are incredibly important to whether the kickline comes off as celebratory of womanhood, versus a parody of womanhood. I think it can be a show of allyship — of exploring something funny, and powerful, and exciting about whatever group of characters has been written about.”

David Walter ’11 is a journalist in New York City.