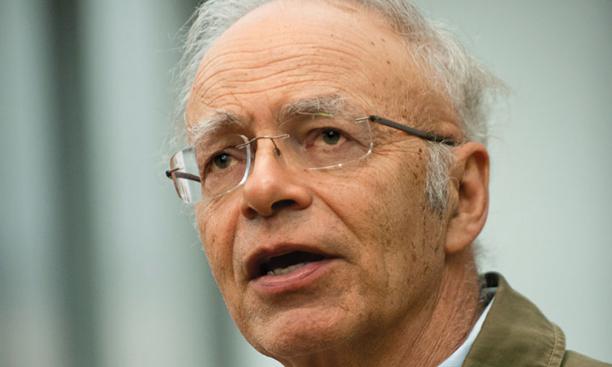

In his new book, Ethics in the Real World: 82 Brief Essays on Things That Matter (Princeton University Press), Peter Singer, the Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at the University Center for Human Values, grapples with some of our biggest, most pressing questions in 1,000 words or less.

Widely recognized as an influential and controversial philosopher, Singer challenges readers’ perspectives on ethical problems in these essays, from abortion and climate change to WikiLeaks and sports doping.A big topic in the book — something you’ve worked on for many years — is animal justice. How have you seen this issue evolve?

Although there’s a long way to go, people are increasingly aware of the fact that animals, like us, experience physical pain and have emotional needs. They can be bored or stressed or frightened. I emphasize the harms associated with the use of animals for food and intensive farming, because I see this as the most important area in terms of the impact we have on animals. In 2008, California passed an initiative requiring that all farm animals have room to turn around and stretch their limbs. The fact that a law was needed to do that enlightened many Californians in terms of how farm animals are living. A lot of corporations now won’t buy eggs from caged hens as a result of public pressure.

Charitable giving — what does it mean to donate effectively?

TALK BACK What guidelines do you consider when giving to charities?

Giving effectively means using your resources to do the most good. If we’re talking about global poverty, we can measure things like the decline in child mortality and say, “We want to do as much of this per-dollar-available.” The issue becomes more difficult when you start comparing different causes. Some, like donations to major museums, can’t compete with organizations that are saving or improving lives. I’ve argued for rationality in giving, a kind of head check on the heart. In the book, I discuss the Make-A-Wish Foundation, which grants wishes of terminally ill kids. But if you can choose between giving a sick kid one or two good days and saving the life of maybe more than one child, the choice seems pretty clear.

How do you respond to critics who say you’ve gone too far on issues like giving the parents of severely disabled infants the option of euthanasia?

Subject to obvious time constraints, I am always prepared to enter into discussion. In the book, I have an essay about my exchange with a disabled woman, Harriet McBryde Johnson, at Princeton in 2002. We continued our conversation over the years, and she wrote an essay for The New York Times Magazine about how our exchange was productive for her. I hope people could see that you can have a reasonable discussion about this question, understand both sides, and make up your mind.

Interview conducted and condensed by Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux ’11