In the various Arab countries I’ve visited, I am an obvious foreigner, so I’ve never been able to slip into an Arabic conversation without comment. Just buying a bus ticket in Egypt, for instance, entails a detour for a mini-interrogation: “Where are you from? Where did you learn Arabic?” I can answer these questions in my sleep: I’m from America. I learned Arabic in college.

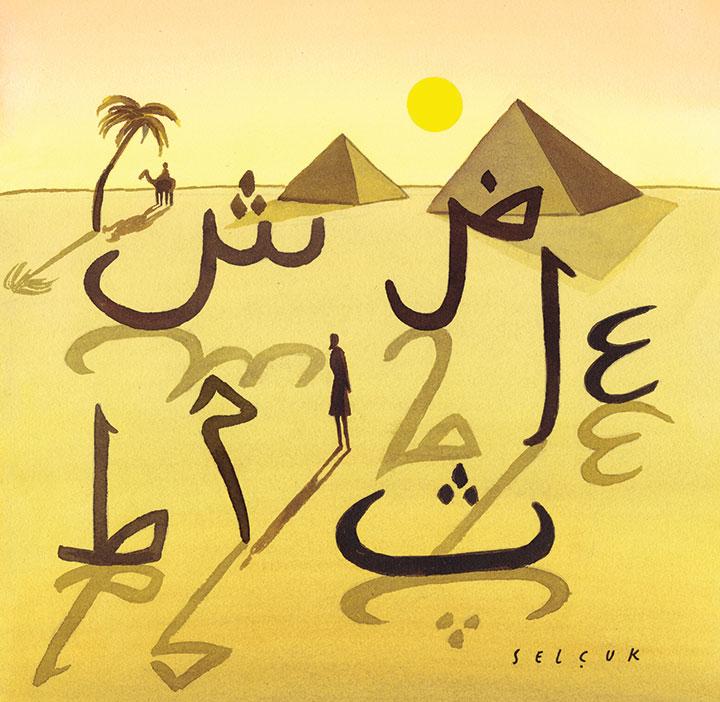

When I began studying, in my first year at Princeton, it was for the usual 18-year-old reasons, all self-centered: What could Arabic do for me? It could make me look smart and interesting and obscure — because nobody studied Arabic back in the early 1990s, and the language is ridiculously hard. It could take me away from my boring old home in New Mexico. In high school there, perversely, I had ignored the massive Spanish-speaking population and studied French. Arabic was a really foreign language that could take me to really foreign lands.

And it did. The summer after my sophomore year, I received a grant to study in Cairo. The crowds, the energy, the thrill of using a foreign language in everyday situations outside the classroom — I was hooked, and I decided to major in Near Eastern studies. (My roommate and I were the only undergraduates to join the department in our year: obscurity confirmed.)

I continued my studies at Indiana University for a master’s degree in Arabic literature, then spent another year in Cairo. But after seven years of increasingly arcane work, I had ceased to feel particularly smart in Arabic, and there seemed to be few jobs outside of academia, at least for people specializing in pre-Islamic poetry. So I left school — but Arabic continued to serve me as I traveled, getting me better deals in markets and invitations into people’s homes, and once, a much-needed lift in a Spanish village, when the only person awake was a Moroccan street sweeper.

For years, my Arabic was dormant. I traveled to other places, learned other languages (after Arabic, every other language is easier; I finally learned Spanish). About a decade ago, after scoring a writing assignment for a guidebook in Egypt, I found myself circling back to Arabic — and that repeated conversation/interrogation. I’m from America. I learned Arabic in college. That was a long time ago, and I’ve forgotten a lot.

Fortunately, native Arabic speakers are encouraging and patient. I’ve been happy to discover that not only do I not need sixth-century poetic vocabulary, but even the rudimentary words I do still have are enough to connect with people, enough to communicate and commiserate and laugh together.

More important, though, is the realization that now I can use Arabic not for myself, but to serve others. In 2011, I decided to write a book about culture and daily life in the Arab world, based on my experience studying there. In 2015, my knowledge of Arabic empowered me to help Syrian and Iraqi refugees in Europe. I helped by printing Arabic information packets, labeling maps in Arabic, politely telling people to line up for food — but most of all, just by listening to people’s stories.

American antagonism toward the Arab world has flourished since 9/11, and news coverage of the latest terrorist activity drowns out reports of the kind, generous people I have met traveling there. Some days I feel powerless against this cultural tide, but I have made it my mission to relate the personal stories I hear from Arabs to people who might not otherwise hear them.

I’m from America. I learned Arabic in college. And I’m still learning and listening every day.