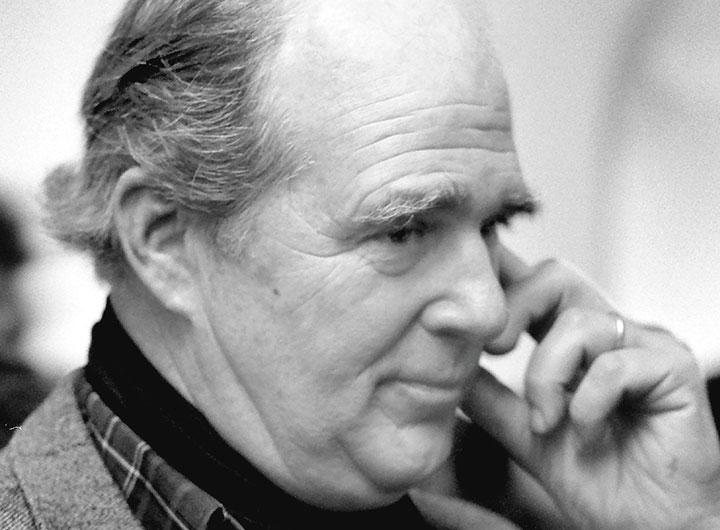

JUNE 25, 1939–APRIL 9, 2016

J. Vinton “Vint” Lawrence ’60 began his career planning a secret CIA military operation in Laos. But intelligence work never defined him, and soon he would transform himself, trading a promising career in government for the life of an artist and caricaturist whose work for magazines and newspapers skewered the powerful.

Lawrence had an affluent upbringing in Englewood, N.J. At Princeton, he majored in art history, played lacrosse, and performed in a Triangle Club pastiche of Swan Lake. After graduation, he followed in the footsteps of his father, James Lawrence ’29, who had been in the Office of Strategic Services, the World War II-era predecessor of the CIA.

Soon after Lawrence graduated, the CIA sent him to Laos, which was home to key supply routes to Vietnam. He was one of a small number of Americans tasked with shaping and advising an anti-communist guerilla army with tens of thousands of mountain-dwelling Hmong soldiers.

He was stationed far from the Laotian capital, with limited electricity and telephone service and few compatriots who spoke English. He had books sent to him and read them voraciously, says Anne Garrels, his wife of 30 years and a foreign correspondent for ABC News and NPR. In Laos, Lawrence was an inexhaustible memo writer. At a CIA reunion years later, Garrels says, Lawrence learned that he had gained some notoriety among agency encoders for “writing prolifically and using very long words.”

The CIA operation in Laos, which remained secret for years, eventually would spiral into massive and sustained aerial bombings by the United States that mostly killed Laotian civilians and kept on killing them for decades after the end of hostilities, due to a legacy of unexploded mines. Lawrence ultimately became a critic of U.S. policy in Southeast Asia, but those who knew him say Lawrence remained committed to the original, more limited vision for U.S. action in Laos.

Years later, “he still thought it was not a bad idea, at least the way it was conceived,” says Joshua Kurlantzick, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations who interviewed Lawrence for his book on the war in Laos, A Great Place to Have a War.

When Lawrence returned from his three-year posting in Laos, he worked as an aide to high-ranking national-security officials including William Colby ’40 and Paul Nitze. But Lawrence never became a lifer. “He realized he probably could have been very good at it, but he wasn’t interested in playing the political game,” Garrels says. “There were also many people at the agency warning him that Laos would be the best assignment of his life, and that he would spend the rest of his career trying to repeat it but would never be able to.”

So Lawrence turned to art. He had little experience, other than some dabbling as a youngster and his art-history degree from Princeton. When Lawrence asked the dean of the Maryland Institute College of Art whether it made sense for him to attend art school, Garrels says, the dean responded, “You will come here and see 19-year-olds who will be drawing like angels and screwing like rabbits. And in five years, most of them will be selling insurance. Go into your attic, and you’ll see if you like being alone and if you have something to say.”

It turns out that he did. Working from his home studio, Lawrence became a contributor to The Washington Post, the Washington Monthly and, most prominently, The New Republic. “His drawings were marvelous — so intricate and funny and insightful,” recalls Peter Beinart, editor of The New Republic from 1999 to 2006. Longtime New Republic contributor Jason Zengerle says Lawrence “embodied the glory days of The New Republic as much as anyone.”

Chuck Lane, Beinart’s predecessor as editor, was particularly fond of a portrait Lawrence drew of Strobe Talbott, a Democratic foreign-policy official Lane had profiled. “You could see how he incorporated all the figures I had covered in the story,” Lane says. “He had Talbott testifying to Congress, while quietly clustered around him watching are Krushchev, Nixon, and all of the 1960s and 1970s figures I had written about.”

Perhaps surprisingly for an illustrator for an opinion magazine, Lawrence didn’t wear his politics on his sleeve. He exuded a bit of noblesse oblige, former colleagues say. Though his caricatures could be devastating, the artist was never strident, says Lane: “He dealt with politics through his wit.”

Lawrence died from complications of acute myeloid leukemia. He was 76.

Louis Jacobson ’92 is the senior correspondent at PolitiFact in Washington.