Two years ago, a fellow Princeton freshman asked Melana Hammel ’18 where she planned to vacation. Her own family usually went to the Bahamas, the classmate explained, but that year they were headed to London.

“In that moment, there was just so much that I just could not explain,” said Hammel, the daughter of a security guard and a home-health aide. “I can’t even remember the last time my family went on vacation.”

As Princeton expands its cadre of undergraduates like Hammel — first-generation and low-income students, known by the acronym FLI (pronounced “fly”) — the University is working to ensure that such misunderstandings don’t burden FLI students with a permanent sense of alienation.

“For a long time, the administration was focused more on college access,” said Brittney Watkins ’16, who in 2013 co-founded the Princeton Hidden Minority Council, a student group that works on FLI issues. “But once you get FLI students there, then it becomes a matter of college success.”

Princeton remains an affluent place: A recent study led by researchers at Brown, Stanford, and Harvard found that the University is one of 38 in the country that enrolls more students from the top 1 percent of the national income distribution than from the bottom 60 percent. But the last class included in the study graduated in 2013, and Princeton officials say the data don’t reflect recent efforts to recruit low-income and first-generation students. Twenty-one percent of this year’s freshman class are eligible for income-linked Pell grants, double the proportion in the Class of 2013.

Princeton data show that FLI students enjoy their college years and graduate at the same rate as more privileged peers, said Associate Dean Khristina Gonzalez, the director of programs for access and inclusion. “Where we see the gaps is in terms of experience,” Gonzalez said — how many fellowships students apply for, how fully they access academic supports like the writing center, how many professors they know well enough to request a recommendation letter.

Two programs — one long-standing, one new — seek to give FLI students a sense of belonging as they negotiate college life amid classmates who come from very different worlds.

In the decades-old Freshman Scholars Institute, 80 students spend eight weeks on campus in the summer before their freshman year, taking two credit-bearing courses and learning about the University’s support services. FSI aims to help students acquire “some of that cultural capital that is particular to elite institutions of higher education, to help them learn to ask for help and to give them a vocabulary for asking for that help,” said Nimisha Barton *14, associate director of programs for access and inclusion.

Last year, the University built on FSI by launching the Scholars Institute Fellows Program, whose academic-year workshops and mentoring sessions aim to help FLI students develop the skills and relationships they need to succeed in college and beyond. The voluntary program launched in the fall of 2015 with 100 students; this year, 300 are participating.

Fellows in the program can choose among workshops on such topics as networking, writing resumes, managing finances, and coping with the stress of family life. “This is stuff that all students need to learn,” Barton said. “The difference, I think, is that first-generation and low-income students don’t have the same personal and interpersonal resources. A lot of students can ask their parents, ‘Hey, can you read through my cover letter?’”

FLI students generally give Princeton good marks for its efforts to support them, though they continue to press for such enhancements as a dedicated space for FLI students and a less onerous summer-work contribution requirement for financial-aid students who must help support their families.

Some also express concern about eating-club membership. Ten years ago, Princeton increased its financial aid for upperclassmen in an effort to make club membership affordable for less affluent students. But some clubs charge fees that total $1,000 or more above the aid the University provides — and to many FLI students, joining a club and borrowing money to close that gap seems foolish, even irresponsible.

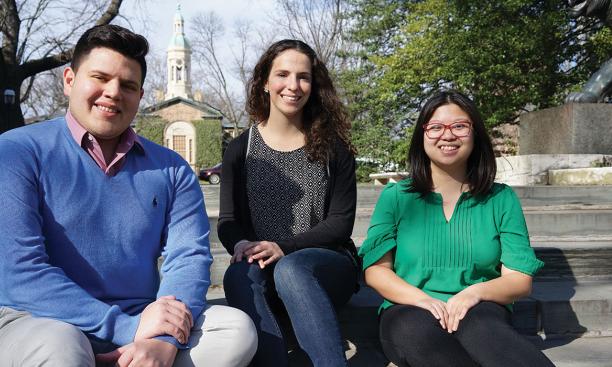

“I just could not justify that to my family,” said Soraya Morales Nuñez ’18, who grew up in Colorado with a single mother who spent years living as an undocumented Mexican immigrant. “It just seems like an outrageous amount of money.”

Instead, some FLI students opt out of meal contracts altogether: My Bui ’18, whose Vietnamese-immigrant single mother works as a manicurist, cooks with friends in a shared on-campus kitchen and pockets the savings from the board portion of her financial-aid package. After graduation, that money could cover car payments or a security deposit on an apartment.

But eating-club membership is about more than money, FLI students say: Some clubs send the subtle or not-so-subtle message that less affluent students need not apply. “The larger issue is a cultural one,” Gonzalez said. “Students make financial decisions; I think that they also make decisions about where they feel that they belong.”

But FLI students note that the emphasis on their challenges can obscure the resilience and commitment they bring to the University. “A lot of the low-income and first-generation students value their time here and their education here more than other students, because they don’t take it for granted,” said Samuel Vilchez Santiago ’19, who left Venezuela as a refugee six years ago. “Those struggles make a lot of us stronger.”