It’s often been said that children who experience early trauma grow up faster. New evidence from molecular biologist Daniel Notterman shows that this might literally be true — all the way down to a child’s DNA. Notterman, who is also a pediatrician, studies the complex interactions between genetics and environment. “I see how disease is often related as much to the underlying genetic substrate as to the lives that children live,” he says. “I want to understand how the environment literally gets under your skin.”

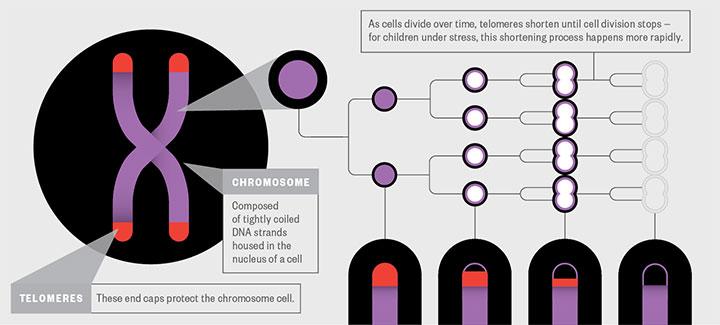

Often compared to the plastic caps on the end of our shoelaces, telomeres prevent the ends of DNA from fraying. Once telomeres become too short, cells stop dividing, weakening the immune system and other important inner functions, hastening the aging process. On average, Notterman found that children who had lost a father through death, incarceration, or divorce had telomeres that were 14 percent shorter than those who hadn’t. (While the group Notterman examined didn’t include enough children who had lost mothers to draw conclusions, he speculates the effect would be similar.)

Telomeres Explained

Not all fatherless children were affected the same way. Those who had restricted access to their fathers because of separation or divorce showed only a 6 percent drop in telomere length, and the study concluded that most of that decrease could be correlated to a loss in family income. “That [finding] suggests that where there is separation but still contact, you could mitigate the effects by targeted resource allocations to these families,” says Notterman. On the other hand, those who had lost fathers to jail or death showed 10 percent and 16 percent shortening, respectively.

In those cases, says Notterman, the loss was so overwhelming that favorable economic circumstances couldn’t make up for it. “Those children might need other forms of social support like a different father figure in their lives such as a grandparent or a Big Brother, as well as some form of therapy,” he says. Even among children who had lost a father, however, there was significant variation in telomere length, depending on their underlying genetics. Identifying those children who seem particularly vulnerable after a trauma, Notterman says, could help doctors target children who are most at-risk with interventions, before they develop health complications later in life.