You may have walked past it without ever noticing: a large marble sculpture of Joseph Henry — a Princeton professor from 1832 to 1846 and one of the most important scientists of his time — tucked into a niche on the exterior of Frist Campus Center, just to the right of the main entrance. Henry looks like a man of action, wearing an academic gown and a look of determination as he takes a step, perhaps on his way to an important experiment. The work was created by Daniel Chester French, a renowned American sculptor who also designed the statue of Abraham Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial. The artist was known for commemorating important people and ideas, so Henry was a natural subject.

You will not find a sculpture of the man who helped Henry execute the experiments that increased his renown: Sam Parker. Parker was a free black man and Henry’s lab assistant, his work so crucial that when he became ill for a short time in 1842, Henry’s experiments stopped.

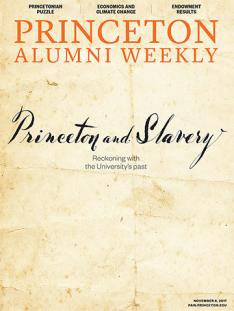

I’d never heard of Parker until I read the essay by graduate student Julia Grummitt, one of about three dozen contributors to the Princeton & Slavery Project led by history professor Martha Sandweiss. Grummitt’s piece, beginning on page 41, is among more than 80 essays posted on the project website, https://slavery.princeton.edu — each one exploring some aspect of Princeton’s connections to the institution of slavery. (The website was to be launched Nov. 6.) This issue of PAW offers three of those essays along with other perspectives on the project.The project developed not by Nassau Hall decree, but out of Sandweiss’ belief that this was an unacknowledged part of Princeton history that deserved to be explored. Over the last four years, the project has grown from a seminar taught by Sandweiss to an effort embracing multiple University departments and community partners. University archivist Dan Linke worked closely with Sandweiss and student researchers to help them find records in Mudd Library and beyond. Principal funders are the Princeton University Humanities Council; the Princeton Histories Fund, which was created in the wake of the debate over Woodrow Wilson’s legacy to explore “aspects of Princeton’s history that have been forgotten, overlooked, subordinated, or suppressed”; Friends of the Princeton University Library; and the Center for Digital Humanities @ Princeton. A symposium Nov. 17–18 will explore the project’s findings; President Eisgruber ’83 will moderate a conversation on how the project “changes our understanding of American history and poses a challenge to historical commemoration.”

The process of rethinking commemoration has already begun. Joining the Joseph Henry sculpture on campus will be a new work by American artist Titus Kaphar, commissioned by the art museum, to be installed in front of Maclean House Nov. 8–Dec. 17. This 8-foot-high mixed-media work, Impressions of Liberty, shows layered portraits of Samuel Finley, fifth president of Princeton, and a family that lived and worked in his home — as slaves.