The book: When the automobile burst onto the scene, it offered access to new forms and ease of travel as well as increasing independence for its drivers, but many questioned whether women should be able to take the wheel. What would happen if women left their duties at home and began to drive?

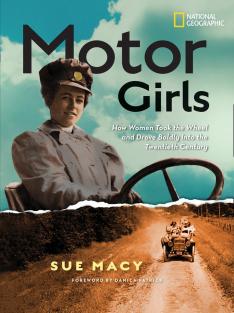

Motor Girls: How Women Took the Wheel and Drove Boldly Into the Twentieth Century (National Geographic Children’s Books) shows how women joined men on the road, despite the protest, and drove their cars for fun, for profit, to set records, and to make a statement about the evolving role of women in society.The author: Sue Macy ’76 concentrated in history at Princeton. She has written many books, including Wheels of Change: How Women Rode the Bicycle to Freedom (National Geographic Children's Books) and Basketball Belles: How Two Teams and One Scrappy Player Put Women’s Hoops on the Map (Holiday House).

Opening paragraphs: “In 1895 Chicago newspaper publisher Herman H. Kohlsaat had an idea that was as crazy as it was inspired. He decided to hold a race for motor cars. Kohlsaat was intrigued by reports that some 300 Americans were tinkering away on motorized vehicles in their barns and workshops. He knew that European inventors had made great advances in building them and that a newspaper in France had sponsored a well-attended motor-car race there the previous year. “The United States is in the rear of the procession in this branch of inventive progress,” Kohlsaat’s Times-Herald declared on July 9, 1895, “while it should be in the front rank.” Toward that end, the paper announced that “Five thousand dollars is hereby offered by the Times-Herald for the successful competitors in a horseless carriage or vehicle motor race between Milwaukee and Chicago.”

Over the next several weeks, more details of the race emerged. All competing vehicles were required to have at least three wheels, thus ruling out motorized bicycles. They could be propelled by gasoline, electricity, or steam. They had to be large enough to carry a driver and one other person, have at least three lamps for nighttime driving and include a trumpet, foghorn, or other devices to warn people and horses of their approach. Each driver would be accompanied by an umpire to monitor his progress. Cash prizes would be awarded to the first car to finish, as well as to other competitors based on their race performance and the results of a battery of scientific tests on their vehicles.

Reviews: Publisher’s Weekly says “Using the lens of automotive history to inform a greater narrative about women’s liberation, Macy capably shows how threads of the past are intertwined.”