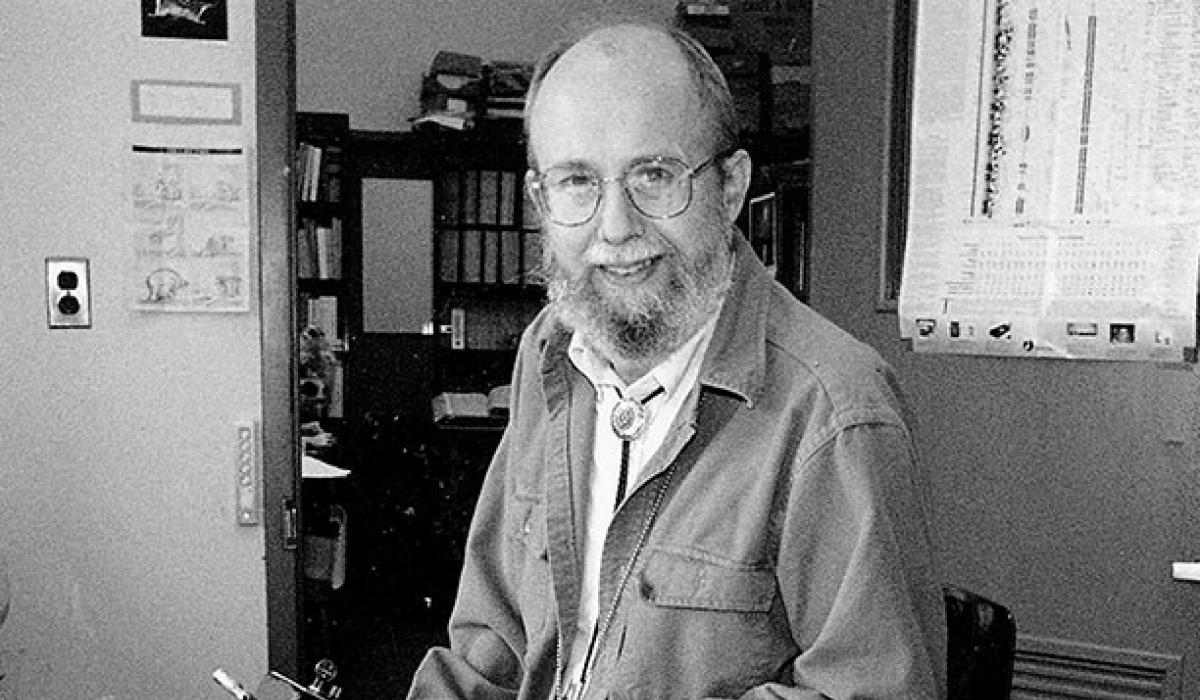

DEC. 24, 1937 | FEB. 24, 2017

RICHARD THORINGTON ’59 MADE his life’s work out of studying the natural world, with research spanning international fieldwork on primates and investigations of squirrels in his Maryland backyard.

Thor, as everyone called him, planned to be a lawyer until a Princeton biology class taught by professor emeritus John Tyler Bonner captured his imagination. He was intrigued by birds, but while at Harvard for his Ph.D., famed biologist Ernst Mayr noted that the job market for ornithologists wasn’t great. Thorington was also interested in mammals, so he became an evolutionary biologist who specialized in mammalogy.

Thorington spent most of his career at the Smithsonian Institution, where he became curator of mammals. He traveled widely for field research, making many trips (including his honeymoon) to Barro Colorado Island, in the middle of the Panama Canal, home to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and a host of animal species. In 1977 he learned he had Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, a progressive neurological disorder. Eventually he became quadriplegic, which he referred to as “a nuisance,” says his wife, Caroline. It didn’t faze him. “He looked to what he could do and not what he couldn’t do,” she says.

Thorington continued his work, aided by voice-recognition software and research assistants who acted as his hands. Caroline, an artist and photographer, increasingly accompanied him on trips. And while he traveled until the end of his life, his research focused more on museum specimens than on fieldwork, she says.

He continued to study local squirrels, and was known as a leading squirrelologist, co-authoring two books about them. He put bead necklaces on the squirrels he caught in his backyard to tell them apart, remembers Caroline. That line of research caught the attention of some neighbors, who misunderstood his attempts to see how far squirrels could jump as lessons in how to vault farther to reach distant bird feeders.

He also loved engaging with students and the public about his passion for the natural world, says Lawrence Heaney, now the Negaunee Curator of Mammals at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Heaney met Thorington as a high school student volunteering and working at the Smithsonian and remembers him as happy to share a conversation with anyone, regardless of age or professional stature, who shared his enthusiasms. “Being treated by someone at his stage as a colleague when you’re in high school had quite an impact,” says Heaney. “He tried very hard to treat everyone the same.”

Thorington maintained an intense curiosity throughout his life, at 60 devoting himself to learning about one unfamiliar taxon of animals a year. Once, says his daughter, behavioral ecologist Katherine Thorington, he was driving his three-wheel scooter to the subway when he spotted a cicada on the sidewalk. He couldn’t pick it up himself, so he recruited a nearby workman to fetch the insect for him and put it in a box Thorington had. The workman, who didn’t speak English but did recognize the word “cicada,” made clear that he thought Thorington planned to eat it for lunch.

“He got his cicada,” his daughter says.

Katherine Hobson ’94 is a freelance writer specializing in health and science.

VIDEO Richard “Thor” Thorington Jr. ’59

Courtesy The Washington Post