In the 1450s, a minor German nobleman named Johannes Gutenberg began printing Bibles using movable type, spurring a revolution in book-making — and reading — across Europe. Although the Gutenberg Bible is a cultural and historical icon today, the Bibles languished in obscurity for hundreds of years after their creation, and many were destroyed. Eric Marshall White, the curator of rare books at the Princeton University Library, spoke to PAW about his book Editio Princeps: A History of the Gutenberg Bible (Brepols Publishers), which traces the journey of the 49 Gutenberg Bibles that still survive and the fragments of 14 others. Princeton’s collection of Gutenberg Bibles includes one “magnificent copy” and fragments from four others.

How many Gutenberg Bibles were originally created, and who owned them?

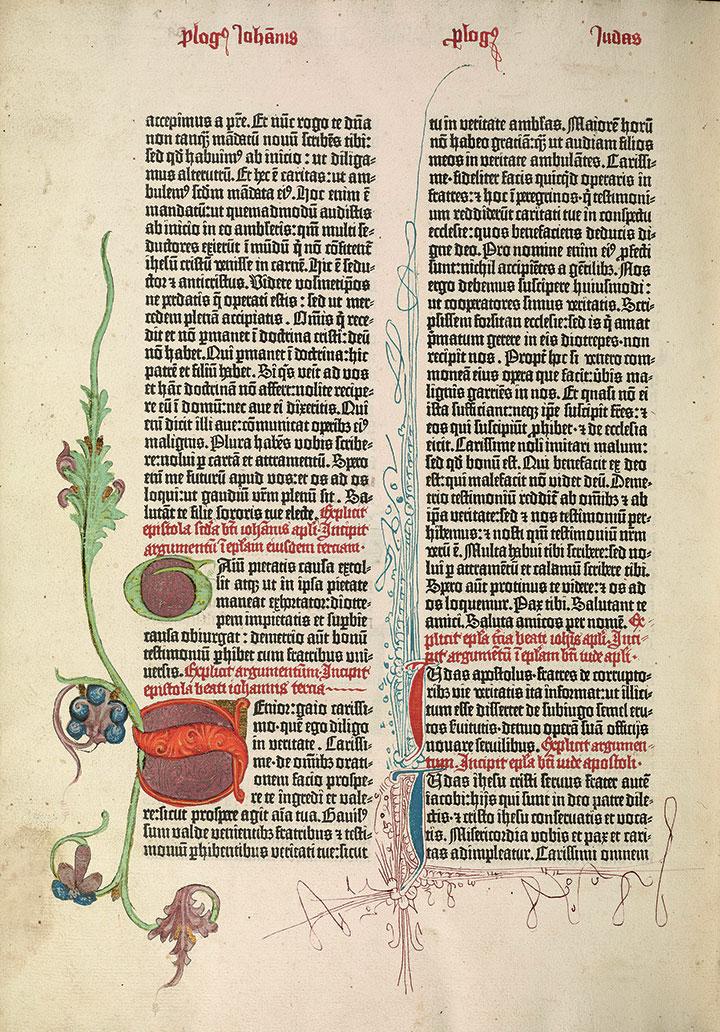

We know that between 158 and 180 were created, mostly printed for the Church, monasteries, and perhaps universities. These were not very affordable — one was essentially equivalent to buying an expensive artwork. But it was seen as valuable because it was a beautiful book, and the text was consistent. Before printing, all of these places had their own copies of the Bible, but they were hand copied, so there was a lot of variation. Having a printed Bible meant that readers who were hundreds of miles apart were looking at the same thing.

The Gutenberg Bible fell into obscurity fairly quickly. Why?

After just a few decades of printing, many other Bibles were available. They were printed in smaller formats, in more legible fonts, and with useful notes — essentially, they were easier to use. Then, in the 16th century, Martin Luther began preaching using his own German translation of the Bible. Gutenberg’s old Latin Bible was of no use for Protestants and it was no longer helpful to the Catholic cause, either. Suddenly a Gutenberg Bible is a lot less valuable, to the point where it’s being recycled by bookbinders who want to use the pages of the Bible — especially those made with vellum pages, which is calfskin — as flexible coverings for cheaper books, or padding in books that were bound in wood. That’s where we’ve found a lot of today’s fragments.

How were the Gutenberg Bibles and the existing fragments preserved?

Some of it was just benign neglect. The librarians who saved Gutenberg Bibles from fires, floods, and bookbinders didn’t necessarily see them as valuable. Many were put in a cabinet and forgotten about — which, ironically, is why some of the Bibles are so well-preserved.

How did the Gutenberg Bible become recognized as an important historical artifact?

Antiquarians — people who collect fine, [old] books — became interested in Gutenberg Bibles in the 18th century. They were interested, at that point, in figuring out the puzzle of these books — where the Gutenberg Bibles had been. That process of tracing the Bibles over time and space has continued for several centuries.

How did you become interested in the history of the Gutenberg Bible?

I became the curator of special collections at Southern Methodist University in 1997, and there were Gutenberg fragments there. I would show these fragments to visitors and say, “This is a fragment of the Gutenberg Bible.” But there was something about that statement that was unsatisfying. The question was always — which one? So I started looking into other Gutenberg Bible fragments and found that a perfect match for our library’s piece was in St. Louis. It actually came from the same calfskin. But there were so many unanswered questions. Theirs was in St. Louis. Where did they get it? Ours was in Dallas. How did it get there? I became fascinated with resurrecting those lost stories.

Describe the detective work that went into that effort.

I had one advantage that previous scholars didn’t have: the internet. You can find things on Google Books — like misspellings of “Gutenberg,” or other names for the Bible — that you just couldn’t locate using paper bibliographies. Science played a part in answering some questions, too. I was able to see that one Bible’s inscription was done exactly in the style of one particular monastery using enhanced imaging.

Sometimes, though, you have to go back to the books themselves. The University of Texas at Austin had a Gutenberg Bible with so many clues. The initials, which were filled in by hand, had been done in an unusual style, and the users had put in markings so they could schedule their prayers according to the liturgical year. I eventually learned that these markings were typical for Carthusian monks — but which ones, where, and when? I noticed that one of the Bible’s bindings was from 1600, which was late. And as I investigated the binding, I discovered that it was from the Netherlands, not Germany like I had expected. That was how I was able to locate where the book had been.

Why is it important to understand the history of the Gutenberg Bible?

Ultimately, although I’ve spent a lot of time worrying about vellum and bookbindings, this is a history of people. Who valued this book? Who didn’t? What world events shaped the map of Europe and the Gutenberg Bible’s place in it? One of the fragments belonged to a Jewish chemist who used it to get out of Germany in 1937 by sending it to Sotheby’s in London to be sold. In a way, that Bible helped preserve his family.

Is this book meant to be the definitive catalog of extant copies and fragments?

Nothing is ever truly definitive in scholarship. My census of the surviving copies and fragments reflects the state of my knowledge in late 2017, but since the book went to press another very nice vellum fragment has appeared in Europe. All I can hope is that my work, which organized the fragments into workable groups representing individual copies, will provide the basis for someone else’s much more complete work in the future, and that their work will lead to meaningful discoveries. I’m confident that the Gutenberg Bible will remain a subject for fruitful study for a very long time.

Interview conducted and condensed by Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux ’11