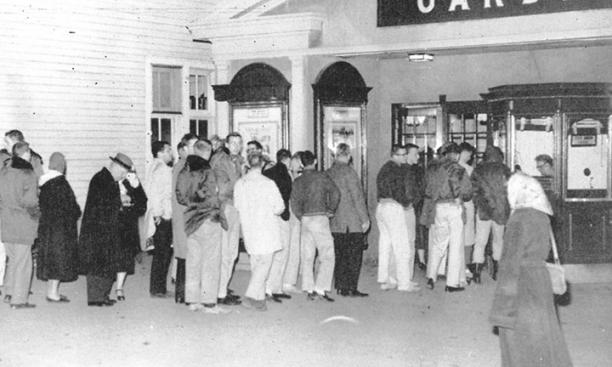

It’s been 60 years since I graduated, and at first sight on a recent visit, the most striking changes are physical: a plethora of large new buildings surrounding and infiltrating the old campus, what were once tennis courts now dorms, woodland now labs, with the promise of much more expansion soon to come. The architecture has become strikingly modern. Once all collegiate gothic, now I find Robert Venturi ’47 *50, Robert Stern, and Frank Gehry. The changes on Nassau Street are more modest. The little Garden Theatre survives. That’s where I saw Brigitte Bardot in And God Created Woman and the devastating documentary Night and Fog, about Auschwitz — rooms filled with human skin, processed to make shades for Nazi lamps.

But the generally funky air of downtown is gone. There’s no sign of the cafeteria lined in subway tile where we ate when we were sick of Commons and “mystery meat.” Langrock, where we used to buy our tweeds, disappeared more than 20 years ago. For that matter, so did the tweeds. My friend Bart Auerbach ’58 remembers walking into Langrock some 30 years after he left and the staff greeting him by name. Now there’s a Brooks Brothers in Palmer Square, and an Ann Taylor, some small boutiques, a shop where they sell nothing but cake, another where they sell only chocolate. Missing is the deli where I was introduced to little tins of chocolate-covered ants and rattlesnake meat. Thankfully, the Nassau Inn is still there. The Tap Room still sports the old wood tables intricately carved with the initials of every student who carried a penknife, but they’ve all been covered with thick pieces of glass. They’re no longer a living University tradition. Now they’re history.

Oh yes, 1958. We’re history, too. Those of us still alive are in our 80s now, our careers, except for writers like me, mostly over, our days given to golf and grandchildren. We were part of what was known as the “Silent Generation.” We were all male and almost entirely white. We never marched, never protested, did not raise our voices, did not join the civil-rights movement being born in the South. Clueless and self-involved, we had no idea we were teetering along the edge of an abyss, that Vietnam was about to change the future, that women’s lib was just over the horizon, that the Pill was going to create the sexual revolution in a year or two. We missed the admission of women to Princeton by a decade. Now women make up half of every class. Diversity has become an old story at Princeton, but to me, it’s astonishing to see.

To be sure, I’ve been back from time to time. On one visit, in 1992, my wife and I went back to my club, a reconstituted Elm Club, and had dinner. In the old days, we wore a coat and tie or we didn’t get fed. We were served by black waiters and waitresses. Wine was on the tables every night. By 1992, there was no dress code; student waiters and waitresses served everyone at what had become refectory tables; and we were treated, if that’s the word, to a food fight.

Bicker was a huge issue in the 1950s, when everyone had to join a club because the University provided no alternative. Bicker lasted two weeks: two weeks of club committees coming to your rooms and engaging you in small talk, sizing up your social savoir faire, your status, your level of cool. Every year, some people weren’t asked to join any club. You would find them sitting on the curbs on Prospect Avenue, weeping. Bicker ruined lives. There are still clubs, of course, but today you have choices. Socially, Princeton has long since been liberated.

I was surprised as well to find that some students today object to the Honor Code. I thought the Honor Code was sacred. I read in The Daily Princetonian that a significant number of today’s undergraduates think the code is draconian, that it should work on a sliding scale tied to the seriousness of the offense, that it is too much about the letter of the law, not enough about the spirit. I confess to being old-school on this one. The Honor Code is about scholarship, the soul of which requires absolute fidelity to the rules. You never cheat, never plagiarize, never look over someone’s shoulder, never etc., and you do none of these things inadvertently. Sloppiness of any kind is forbidden. I’ve spent my life as a writer, subject to the rigors of fact-checkers on the staffs of the magazines I’ve written for, and they don’t fool around. For that I’ve been deeply grateful. It’s my name on the piece, my reputation that’s at stake. Honor is an old-fashioned concept, but in a time like the present, when it’s so hard to find, a university is an appropriate refuge for it.

One thing that hasn’t changed about Princeton is the quality of the education. I was an English major, and on my visit in April I thought it would be interesting to find an English class to attend. The department kindly steered me to one on John Milton that fit my schedule. I had never taken a course on Milton. He was out of favor in the ’50s. I remember one of my professors writing a note on a paper I had written about poetic imagery in Christopher Marlowe comparing Milton’s “sonorous metal blowing martial sounds” to Shakespeare’s “silver snarling trumpets,” and deciding then and there I didn’t have to read Milton. Now I’m not so sure. This class was a lecture, and the lecturer was so energetic, so enthusiastic, striding back and forth across the low platform at the head of the class, and in the end so convincing that he changed my mind.

It’s difficult to characterize this generation of Princeton students with a phrase the way that “Silent Generation” summed us up in the 1950s. One student said that her time at Princeton was a process of finding out who she is as an individual, and others concurred. One thing that does characterize them is the stress level. A young man told me that he was working 150 percent of his time, and in fact he did look harassed. Everyone I spoke to — students, faculty, administrative staff — mentioned this. The students’ busyness, the stresses of competition, their ambition also keep them too busy to engage in politics much, which surprised me. But I imagine it’s still true that if you enter Princeton conservative, you usually leave it liberal.

If today’s students aren’t active politically, they occasionally march. They joined the national protest against America’s gun culture last spring, rallying near the public library. In my day nobody marched, except for the lone student who used to picket Nassau Hall against nuclear weapons. Students today also volunteer, and I wonder if the town’s ambulance squad would exist if not for the undergraduates who participate. In comparison, my class looks more than a little pathetic. I used to characterize my classmates as, for the most part, fledgling bond salesmen. But in fact, great men emerged from my class. The painter Frank Stella. A Rockefeller — Steven — who chose not to become a public figure and went into academe instead. Jack Danforth, scion of the Purina-Ralston feed company and U.S. senator from Missouri for almost 20 years. Gordon Wu, perhaps our only Chinese student, who returned to Hong Kong and made a fortune building infrastructure in China. He is now Sir Gordon Wu, and one of Princeton’s largest benefactors. Maybe we weren’t so bland after all.

I used to hide my Princeton heritage. I didn’t want to be stereotyped as your typical upper-crust snob with a Princeton degree. Now I cherish it. My education made me, ignited my intellectual curiosity, turned me into a lifelong learner, gave me the confidence to sail out on my own and live by my wits. “I would say that we’re being awakened,” one of the young women in the Milton class said to me about what Princeton was like now. Awakened. Enlightened. This is what great universities do, and Princeton is still clearly doing it. We can all be proud to have gone there and been awakened.

A Call for Alumni Voices

Throughout the year, PAW will publish essays by alumni on a wide range of topics that could help other alumni navigate through careers, family issues, and ethical dilemmas, among other things. Essays can be serious or funny, but they should have a strong voice. Send your idea — not a completed essay — to pawessay@princeton.edu.