Alumni occasionally ask me how Princeton’s current undergraduates differ from preceding classes. I try to respond cautiously. Generalizing about the student body is almost always a mistake.

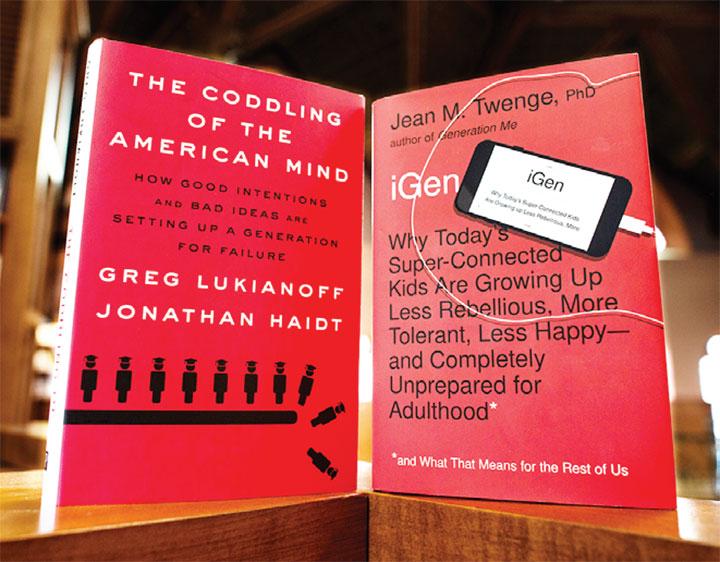

Generational trends can, however, be illuminating if we keep in mind that they describe statistical tendencies not inflexible rules. The best study that I have encountered comes from Jean Twenge, a San Diego State University social psychologist. She has written a fascinating book with a hyperbolic title: iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood.

The idea that an entire generation is “completely unprepared for adulthood” is of course preposterous. Today’s kids will muddle imperfectly through life’s challenges, as human beings have done for millennia.

Title aside, though, Twenge’s analysis is compelling. She begins with the observation that students today “grew up with cell phones, had an Instagram page before they started high school, and do not remember a time before the Internet.”[1.] Twenge and her colleagues have surveyed middle school and high school students for more than 30 years. That data enables her to examine how technology is affecting the habits and thinking of young people.

Nobody will be surprised to learn that kids (and the rest of us!) nowadays spend a lot of time on our phones. Far more interesting are the correlations Twenge finds between online activity and other behavior. For example, teenagers today spend less time hanging out with friends than did predecessor cohorts: instead of getting together, kids text each other. Meanwhile, young people report declining happiness and increasing mental health issues. The risk of unhappiness increases with time spent texting but—and this may surprise some parents—decreases with time devoted to homework.

Twenge offers two explanations for why social media might decrease young people’s happiness. One depends on the content of what kids read: some of it is bullying, and some of it makes kids aware of events from which they have been excluded (aggravating what people hipper than me call “FOMO,” or the “fear of missing out”).

The second explanation has to do with the simple fact that online activity, whatever its content, displaces more meaningful contact. Twenge plausibly suggests that “inperson social interaction is much better for mental health than electronic communication … humans are inherently social beings, and our brains evolved to crave face-toface interaction.”[2.] Communicating through social media is tempting because it is easy, but it is ultimately more superficial and less rewarding than getting together.

Twenge’s book also identifies a number of respects in which today’s young people defer milestones—such as getting a driver’s license—traditionally associated with “coming of age.” Whether because of technology or not, Twenge’s data suggest that today’s college students arrive on campus with experiences that make them on average less independent, and more safety-conscious, than preceding cohorts.

Twenge’s research features prominently in another interesting book with an unduly apocalyptic title, Jonathan Haidt’s and Greg Lukianoff ’s The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. Haidt and Lukianoff are concerned about recent campus free speech controversies, especially those in which students sought to suppress ideas with which they disagreed.

Free speech and vigorous argument are essential to any great university, and I share Haidt’s and Lukianoff ’s concern about awful events like the violent protests that occurred at Middlebury when Charles Murray spoke there. I do not, however, believe those episodes tar an entire generation. Haidt and Lukianoff have an unfortunate tendency to generalize from outrageous examples.

Still, The Coddling of the American Mind is worth reading. Haidt and Lukianoff identify multiple social trends that have intersected on college campuses in recent years. These include nationwide political polarization, the rise of social media and its impact on mental health, changes in parenting practices, and a series of searing political controversies about race and other topics.

Most of the advice that Haidt and Lukianoff give to universities at the end of their book is also quite sensible. They recommend, for example, that universities adopt the Chicago principles on free speech, which Princeton did in 2015. Haidt and Lukianoff also suggest that universities should explicitly acknowledge and emphasize the importance of truth-seeking to their mission. That point has been at the heart of discussions prompted by this year’s Princeton Pre-read, Professor Keith Whittington’s Speak Freely: Why Universities Must Defend Free Speech.

Ultimately, this advice is sensible precisely because it recognizes that if today’s students are different from their predecessors, it is not because they are being “coddled” but because they have grown up with different technology and social structures. Communicating wisdom across such differences is a challenge, which is why teaching is an art. Educating the iGeneration will demand innovation from teachers and professors today, just as our predecessors had to invoke their own wit and creativity to educate us.

1. Twenge, p. 2

2. Twenge, p. 88