In the past decade, the U.S. government provided billions of dollars in funding and incentives for renewable energy sources such as wind and solar power to cut down on carbon emissions. It has provided comparatively little, however, to capture and remove those emissions from the atmosphere. “Carbon capture is way behind other technologies in its deployment,” says Ryan Edwards *18, a Ph.D. in civil and environmental engineering and AAAS Congressional Science and Engineering Fellow in the U.S. Senate, “but we know from study after study that it is one of the key, important technologies we need to meet the world’s climate targets.”

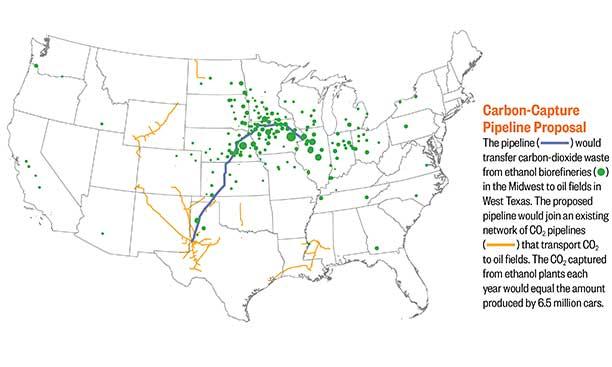

Congress passed a new tax credit in the 2018 Bipartisan Budget Act, which created an incentive for companies to capture and store carbon. According to a new paper by Edwards and his adviser, Princeton Environmental Institute director Michael Celia, however, that credit may not be enough on its own. Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in September, the study argues that the biggest opportunity to capture carbon effectively and make an impact is by building a pipeline network to carry carbon from sources in the Midwest to Texas, where it can be repurposed — and for that, more government support would likely be needed.

“Essentially, all studies of a carbon-limited energy future involve massive amounts of carbon capture and storage,” says Celia, whose lab has been investigating the logistics of carbon storage for years. “The pipeline development would be a first step in this massive escalation of carbon-capture activities.”

The cheapest emissions to capture come from ethanol plants whose emissions are 99 percent CO2, which can be captured for an economically viable price of $20 to $30 a ton. (Coal plants produce only 10 to 15 percent CO2, making it more than twice as expensive.) The majority of ethanol plants are in the corn-rich region of Iowa, Illinois, Nebraska, and other central states, which do not have the kind of geological formations necessary for storing carbon. Trapped carbon dioxide from ethanol plants could be used by the oil industry in Texas, which could inject it into oil fields to create higher yields from its wells. “Republicans like that because it helps the fossil-fuel industry, and Democrats like it because it reduces emissions,” says Edwards.

In the researchers’ analysis, the system could only be financially feasible if the government provides low-interest loans to help finance the $6 billion or so it would take to build the pipeline and capture-facility infrastructure. But the government would be repaid over time, and meanwhile some 30 million tons a year of CO2 could be removed from the atmosphere — an amount equivalent to removing 6.5 million cars from the road. Fossil-fuel companies would make money on the deal as well, producing more oil and increasing American energy security. “You don’t even have to believe in climate change to think this is a good idea. It’s a win-win,” says Edwards.

“It’s a big project,” he admits, requiring thousands of miles of pipeline, “but it’s not unprecedented when you look at how many miles of natural gas pipelines get built in the U.S. every year.”