Encouraged by the University’s commitment to the war effort, thousands of Princetonians served in World War I. That group included almost 90 percent of the Class of 1918, plus alumni with class years ranging from 1862 to 1921. For Horne Jr., Class of 1913, military service was not an option — he was rejected due to poor eyesight — but he volunteer to serve on the front lines as an ambulance driver.

In May 1918, Horne reported to New York for a crossing to Bordeaux. There were 120 new drivers onboard, including Ernest Hemingway — a teenaged writer, fresh off a job at the Kansas City Star. He befriended Horne on the Italian-Austrian border, where they transported wounded soldiers and ran supply lines. When provisions dwindled, a restless Hemingway pedaled a bicycle to the front and eventually was shot by Austrian soldiers while rescuing a wounded companion.

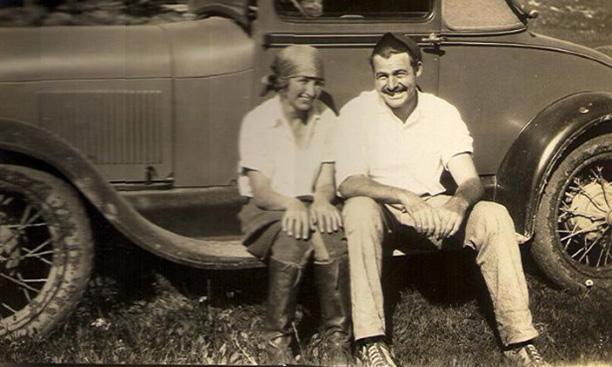

They didn’t see each other until the end of the war, but “Ernie” and “Horney” remained friends. Horne found work in Chicago, selling axles. It was lucrative but unfulfilling. Hemingway was struggling to support himself, so Horne wrote and offered “to grubstake him while he became a writer.” A week later, they were roommates.

Their friendship would last for decades beyond the war that brought them together. Horne visited Hemingway in Cuba in 1958, and they exchanged letters until Hemingway’s death in 1961. (Some of the letters are available to researchers in the William Dodge Horne Collection of Ernest Hemingway at Firestone Library.) PAW published Horne’s reflections on their friendship in 1979.

First Person: The Hemingway I Remember

By Bill Horne 1913, as told to Virginia Kleitz Moseley

(From the Nov. 11, 1979, issue of PAW)

In May 1918, I went to New York City to report as a volunteer ambulance driver for the Red Cross in Italy. The U.S. had entered the war in Europe but would have no troops ready for another month, so the Red Cross was sending ambulance sections, with huge American flags painted on the sides, as a way of telling the Allies, “Boys, we’re with you!” Among the 120 drivers recruited from all over the country—mostly the halt, the half-blind like me, the too young and too old—was a handsome, 18-year-old giant named Ernest Hemingway. He had signed up in Kansas City, where he was a cub reporter for the Star.

We sailed on the French Line ship Chicago, said to be U-boat proof because the spies went back and forth on it. During the ten-day crossing, Ernie and I became good friends. We landed at Bordeaux the day the enemy was stopped at Belleau Wood, and all of us got high on the native product. Though honorary second lieutenants in the Italian Army, we were just kids, and getting half a bottle of wine into you was pretty serious business. We took the nighttrain to Paris and were received as persona grata. We were even saluted by French generals!

From Paris we proceeded to the American Red Cross headquarters in Milan. After a few days, we were sent to five stations, or sections, about 20 miles behind the mountain front. Our ambulances would fan out from the town of Schio at the west end of the Italian-Austrian line, and we’d cover our sectors a little east of Lake Garda, bringing in the wounded. By great good fortune I was assigned with Hemingway, Fred Spiegel, Larry Barnett, Jerry Flaherty, and “Little Fever” Jenkins to Section IV, which we came to call the “Schio Country Club.” For nearly 60 years they were my dearest friends but now all are gone except me.

In early June, during a lull on our end of the front, an officer came through, recruiting men to go to the Piave River. There the offensive was hot, and men were needed to run the canteens. Everyone from Section IV volunteered, and eight were chosen, including Ernie and me. I was dropped at the 68th Brigata Fanleria, San Pedro Novello, one of the little villages, and Ernie went to Fossalta.

We lived in a half-blown-apart house and no one brought us supplies to dole out. Ernie grew restless, so he borrowed a bike and pedaled to the front. He was at an advanced listening post—a hole in the ground—when the Austrians discovered it and sent over a Minenwerfer. It landed right smack on target. One man was killed, another badly hurt, and Ernie was hit by shell fragments. He dragged out his wounded companion, hoisted him on his back, and headed for the trenches 100 yards away. The Austrians turned their machine guns on him and he took a slug under one knee and another in the ankle, but he made it.

Ernie lay in a surgical post until another ambulance driver came along and identified him. They took him to the front-line dressing station, then to the Red Cross hospital in Milan. That’s where he met Agnes von Kurowsky, an American volunteer nurse. They fell in love and planned to be married.

After the Piave line became stable, I returned to Schio and relative calm until late fall, when the Allies started the Vittorio Veneto offensive at the Adriatic mountain end of the line. One night I drove our N.8 Fiat to Bassano to see Ernie, and we had a jolly time together. Later, he got jaundice and was returned to Milan. Meanwhile, I went to the front line atop Mt. Grappa and had a steady week of carrying wounded until the battle was over. In November, the war in Italy ended.

It took only a few days for the Red Cross to say, “Break ’em up and send ’em home.” The difference between war and peace was like night and day, with no dawn in between. After a short leave, I picked up my footlocker at Section IV and six of us left for the U.S. on the French liner Lorraine. Ernie remained behind in the Milan hospital. They had taken out 250 pieces of metal and were giving him muscular therapy.

He sailed on the Guiseppe Verdi shortly after New Year’s 1919, wiring me the time of arrival. I met the boat, and he was a darn dramatic sight: over six feet tall, wearing a Bersagliere hat with great cock feathers, enormous officer’s cape lined with red satin, a British-style tunic with ribbons of the Valor Medal and Italian War Cross, and a limp! The New York Times carried a front-page story and a picture headlined, “Most Wounded Hero Returns Today.” Heads turned as we walked uptown to the Plaza to meet my best girl for tea. When she saw Ernie, she hardly even said hello to me.

Ernie stayed with me a few days in Yonkers before returning home to Oak Park and a hero’s welcome. That spring while he was adjusting to being back and trying to write at his parents’ summer place in Michigan, he received a letter from Agnes, who was still in Italy. She wasn’t going to marry him. Ernie was heartbroken.

It was two years before Ernie and I got together again. I was in Chicago, terribly miscast selling axles, but I was making $200 a month. So I wrote Ernie, suggesting he let me grubstake him while he became a writer. I thought he had talent, though I had no idea how much. He was a dear friend, still sad about Ag, wanted to come to the city and write, but needed money to live on. With my fabulous salary and $900 savings, I was feeling rich—we could live on that a long time.

He wired that he was coming, and a week later we had a happy reunion. We rented a fourth-floor room in a house at 1230 N. State Street. It was the kind with a washstand in the corner and a bath down the hall. Meals weren’t included, so we usually ate at Kitso’s, a Greek restaurant on Division Street. It was a quick lunch place with tables, a counter, and a hole in the wall for shouting orders into the kitchen. They served pretty good dinners for 65 or 70 cents, and I think Kitso’s was the scene of Ernie’s story, “The Killers.”

We often got together with our war buddies, feeling like kids who had been in the same high school class, then separated for a few years and reunited. We would eat at one of the Italian restaurants on the near North Side, and turn up our noses just a little at guys who hadn’t been in Section IV and shared our great experience.

After some months at the roominghouse, Kenley Smith—brother of Ernie’s oldest friend, Bill—invited us to move into his apartment around the corner on Division Street. He and his wife had plenty of space and liked to have a lot of people around. It was an exciting atmosphere. Kenley was an erudite advertising man, with lots of intellectual friends like Sherwood Anderson, who had been a copywriter in his firm. On winter evenings, we’d sit around the fireplace and Ernie would read his stories with Sherwood commenting. Anderson recognized Ernie’s talent.

Of the many people who visited the Smiths, one particular girl, Hadley “Hash” Richardson, managed to cure Ernie of his broken heart. In fact, it was love at first sight. Soon after she returned home to St. Louis, Ernie and I went there to visit her for a long weekend. We had great fun making gin by boiling the ether out of sweet spirits of nitre over an open-topped burner. It was a silly thing to do, as it was very explosive and we got only about two teaspoonfuls of liquor. By the time we left, Ernie and “Hash” were certainly engaged.

I was an usher at their wedding the following summer. The newlyweds lived for a few months in Chicago but their hearts were set on going to Europe where so many aspiring writers were congregating. Ernie got letters of introduction from Sherwood Anderson, made a deal to report for The Toronto Star, and set off on his second voyage to Europe.

In August 1923, Ernie and “Hash” returned for “Bumby” to be born in America. We saw each other several times, and he gave me a copy of a little volume of his work which had been printed in Paris under the title, Three Stories and Ten Poems. He inscribed the book’s gray paper cover with a personal note beginning, “To Horney Bill ... “ (Of all things, I lost it during the next few years of moving from one place to another. Last year I saw a copy offered by a London bookseller. The price was $3,500, without any personal inscription.)

Ernie’s next book of stories, ln Our Time, was published with the help of my classmate Harold Loeb ’13, one of the young American expatriates in Paris who became a tennis and drinking companion of Ernie’s. Loeb’s novel, Doodab, had been accepted by an American publisher and he had gone to bat for Ernie. When Ernie got up a party to see the bullfights in Spain, Loeb went along. But in his first novel, The Sun Also Rises, Ernie cast Loeb as the heavy. Thirty years later, Harold wrote a book called The Way It Was, basically a rebuttal.

In the summer of 192 8, Ernie returned to the States again with his second wife, Pauline, so their baby could be born here. After Patrick’s arrival in Kansas City, Pauline was resting at her parents’ Arkansas home. Ernie wrote to me in Chicago, suggesting we go west and do some fishing while he finished his novel, A Farewell to Arms.

I took the train to Kansas City and Ernie met me in his Ford runabout. We drove across a corner of Nebraska, up the Platte into Wyoming, and bumped over rocks and ruts in the Red Grade road, climbing the Big Horn Mountains. As we snaked around hair-pin turns with steep drop-offs, I kept saying. “Look out, Ernie!” He endured it patiently and finally said, “Do me a favor, Horney, when you get out, just close the door.” I didn’t peep after that.

On a plateau 8,000 feet up, we reached our destination, the Folly Ranch, owned by Eleanor Donnelley. At least 16 lovely girls, mostly Eleanor’s Bryn Mawr classmates, were waiting to greet us—including my future wife, Frances “Bunny” Thorne. The place turned out to be heaven, or a reasonable facsimile thereof, with a swell cook, Folly the collie, and some active trout ponds.

Bunny’s log of that summer records some of the high spots: bridge, dancing, singing around the piano, and one night, “with his hands doing most of the talking, our author gave us the low-down on Dorothy Parker’s and Scott Fitzgerald’s burning inspirations. Then he was distracted by a bull-fight.” I think he was the matador and the bull.

Ernie loved ranch life, not to mention being admired by all the girls, but he had taken too much time off from his writing. After I left, he retreated to a quieter cabin to work on his book. He finished A Farewell to Arms that summer, and when Bunny and I were married the following year, he gave us a first-edition presentation copy.

While at Folly, Ernie and I had studied a map of Wyoming and Montana with an eye to future fishing. He pointed out a lonely looking stream that started in the north, went for miles along Yellowstone Park’s wild eastern edge, looped down south through wilderness, and finally swung north to the Yellowstone River, hundreds of miles and two mountain ranges away. “Horney,” he said, “that’s the place. Someday you and I will go there and slaughter ’em!”

Two years later we did. Ernie was always right about a map or trout, and the stream he picked was the Clark’s Fork of the Yellowstone. Bunny and I went to join him and Pauline at Lawrence Nordquist’s L Bar T ranch in the northeast corner of the Park. We spent a day or two getting to Yellowstone on the train, then a bus took us across the western half of the Park to old Cook City, Montana. There the group met us on horseback, with mounts for us, and I can still see Ernie on that big steed. He rode straight-legged, Indian fashion, because of his gimpy knee, and he looked like the man who invented Montana.

It was a nine-mile ride down the southerly valley, past Index and Pilot peaks. We arrived before dusk. The land rose above the Fork’s east bank into steep hills and hogbacks. There were narrow stretches of forest, green and yellow steps leading to the ridges of Beartooth Buttes, 15 miles away to the east. We had the happiest time imaginable, although for a while it rained and the trout hid behind rocks. Finally the rain stopped, and I’ve never seen anything like it in the way of stream fishing. We were using mostly wet flies, usually a McGinty at the end of the leader and two droppers along its length. The fish were so hungry and profuse that many times we had two on at once, occasionally three.

Ernie, who was then writing Death in the Afternoon, had brought along bushels of Spanish bull-fighting periodicals. We were at a spot where the river was about to dive down into a canyon, fast beautiful water full of trout, the kind of thing an avid fisherman would sell his soul for. Yet morning after morning, Ernie sat in the sun in an old rocker, reading the latest on corridas.

He was enjoying his fame then, and I remember him as dominant, exuberant, damned attractive, a stand-out in any group. But when he was with his friends, he was with them, not apart from them.

The last time I saw Ernie was in the spring of 1958, when Bunny and I visited·him and Mary, his fourth wife, at the Finca, their lovely country house in Cuba. He was the bearded “Papa” by that time. In the evening, they took us to dinner at Floridita, the restaurant Ernie had made famous. We were much impressed with Mary—she seemed a fine wife for Ernie.

Ernie died on July 2, 1961—the same weekend that we were having a Section IV reunion at Jerry Flaherty’s. I remember the headline: “Own Gun Kills Hemingway.” It was hard on all of us; nobody had thought to invite him from Idaho, and maybe it would have helped his depression. Mary wired, asking me to be an honorary pallbearer, and everyone was giving me messages of condolence to carry. But because of the holiday the banks were closed and I didn’t have enough cash to make the trip. Fred Spiegel came to my rescue: “I’ve been to the Arlington track and did pretty well. How much do you need?” I told him about $300. He took out a roll of bills and peeled it off.

So with a little help from Section IV, Bunny and I flew out to the funeral. The graveside service was on a hill outside Ketchum, under a blue sky with the Sawtooth Mountains as backdrop. Everyone there had some bond with Ernie. Mine was having been an ambulance driver with him in Italy. Also, I was the first of a dozen or more Princetonians—including, most prominently, Scott Fitzgerald ’17, a classmate of my younger brother, Jimmy—who had played important roles in his life. Though there were long gaps when we didn’t see each other, we kept in touch for 43 years. Ernie and Bunny have been the two great things in my life.