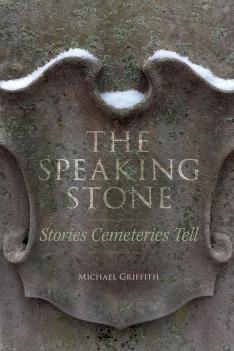

The book: The Speaking Stone: Stories Cemeteries Tell (University of Cincinnati Press) by Michael Griffith ’87 presents a series of essays on the discoveries made wondering the graves in Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati, the nation’s third-largest resting grounds.

The book presents the lives of different people via the traces they left behind at their burial sites. Through an exploration of the cemetery, Griffith tells stories of ambition, struggle, and death in the lives of ordinary people, investigating what we choose to leave as monuments to after we are gone.

The author: Michael Griffith is the author of the novels Trophy and Spikes and the story collection Bibliophilia. He is a professor of English at the University of Cincinnati.Opening lines: I’ve long been an avid reader of obituaries. They’re the only kind of story in the newspaper – in the whole hot-take mediasphere, for that matter – that features a completed arc, with beginning and end, rather than being a chaotic dispatch from the middle of things. Obituaries follow a stately, near-universal template; one that’s elegantly improvised upon and compressed, a strict poetic form: the ghazal of a life, the sonnet. Especially since, roughly half a century ago, with the rise of obituaries about ordinary people – a form that took on a special poignancy in the aftermath of 9/11 – obituaries can offer the reader a sense, too, of the multifariousness of the paths not taken, of the range of occupational choices and ways of contributing to (or wrecking) humanity.

One day a couple of years ago, for example, I recall reading an obit for Leo Hulseman, inventor of the red Solo Cup, enabler of Toby Keith songs and college Greek scenes. Alongside him that day were Marilyn Sachs, the author of, among other books for young people, the classic A Pocketful of Seeds, about a young Jewish girl in occupied France whose parents are taken away by the Nazis; George S. Irving, voice of the Heat Miser from Rankin/Bass’s unkillably wonderful/awful stop-motion special The Year Without a Santa Claus; Debbie Reynolds, the Unsinkable Molly Brown herself, sunk by a stroke just one day after the sudden death of her daughter, Carrie Fisher; and Tyrus Wong, the Chinese-born artist who, by channeling Song Dynasty landscape paintings, gave Bambi its spare, haunting, distinctive look (but was for decades deprived of the credit).

As Marilyn Johnson points out in her book The Dead Beat, all you have to do to find synchronicities and compelling links on the obituary page is to pay attention, maybe squint a little. The messy partisanships and envies of daily life make “only connect” a hard motto to live by; but note how quickly death whisks away the obstacles, how efficiently the conventions of the obituary speed the path to reconciliation. Among their other accomplishments, three of the dead that day were luminaries of animated films: Irving, not only the red-faced “Mr. Hundred and One” but also the narrator of Underdog; Reynolds, who contributed in the holiday hokum category, too, as Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’s mom, and who also, unforgettably, gave voice to E.B. White’s philosopher-spider Charlotte A. Cavatica; and the great cell artist Wong.

Let’s claim Irving for the lighter side of kids’ entertainment (leaving aside Underdog’s penchant for collateral damage, the Heat Miser’s tragic Midaslike tendency to melt things in his clutch). And, sure we’ll stipulate that Hulseman will be remembered not for his business acumen, or for saving noses and laps from coffee-scorching with his “Traveler Lid,” but for his status as Patron Saint of Tailgating, Dark Lord of Beer Pong. (No one’s dignity could survive Toby Keith’s par-tay anthem “Red Solo Cup,” with its opening rhyme of “receptacle” with “testicles,” then its beeline into the chorus of “Red solo cup I fill you up/ Let’s have a party let’s have a party.”)

The other three, though, make up a mini-pantheon of Death in Children’s Entertainment. Sachs, who built her best-known novel around collaboration and the Holocaust. Reynolds, who as the minuscule heroine of Charlotte’s Web taught Wilbur the pig, Fern the flinty farmgirl, and the rest of us a hard lesson about mortality (and who as consolation left 514 eggs, a legacy that seems almost cruel in the context of Reynolds’s death, since – an awful reversal of the “natural” order – she was immediately preceded in it by her daughter). And Wong, a man in large part responsible for the tone and power and terrible beauty of the first, most desolating screen death I ever witnessed. Lesson of the day’s death notices? Red Solo Cup, I fill you up with anguish.

But what I like best about obituaries, as about most of the fiction I love, are not the plot elements (feats and honors, in this case) but the pungent oddities that peek up between and around them; quotations, anecdotes, details offered as a synecdoche for a whole life. These are the elements that give the reader, having invested just two or three minutes, something of a person’s tone and timbre. Obituaries are miniatures that, in the hands of a sly, resourceful, about all empathetic writer, don’t just transcend the forms’ limitations but are in some basic way about showing how obnoxious and deficient linearity is as a way of viewing a life. They give a useful reminder: the real life lies between the lines.

Review: “Griffith is a master storyteller. He begins finitely and then goes everywhere, and we readers are delighted to go with him. He makes the local, universal. This book will appeal to readers everywhere.”

― David Kirby, Florida State University