Find more PAWcasts online here

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

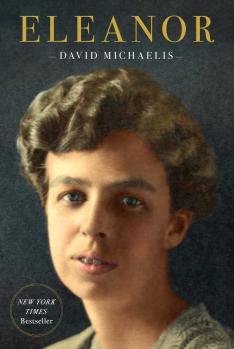

Eleanor Roosevelt was many things: an orphaned child in a prominent family, a stellar student, an ambitious social reformer, a savvy political spouse, a tireless humanitarian, and a syndicated columnist whose daily dispatches were followed by millions of readers. According to David Michaelis, author of the new biography Eleanor, the former first lady built a remarkable legacy by engaging with the public and pursuing her passions. “She truly was a far more evergreen person, in a way, even than her husband,” Michaelis says, “because she kept growing.”

TRANSCRIPT

Brett Tomlinson: Welcome to the PAWcast. I’m Brett Tomlinson. Our guest this month is biographer David Michaelis ’79. He’s written critically-acclaimed portraits of two artists, N.C. Wyeth and Peanuts creator Charles Schultz, and his latest work, Eleanor, explores the life of one of the most remarkable women of the 20th century, Eleanor Roosevelt. She was first lady for 12 years, spanning most of the Great Depression and the Second World War. But as David makes clear, Eleanor’s influence, as a humanitarian and as a savvy politician, predated the Roosevelts’ time in the White House, and continued in the decades following her husband’s death. David, thank you for joining me.

David Michaelis: Thank you, Brett. Thanks for having me. Great to be here.

BT: I’m anxious to talk about the book, but I want to start with a bit about your path as a writer. You were an English major at Princeton, is that right?

DM: I was, yes.

BT: And by the time you had finished your senior thesis, you had already co-authored a book with another Princetonian, John Aristotle Phillips [’78], who had written his junior paper on how to design an atomic bomb. Quite a story there. But did you graduate hoping to write nonfiction as a career?

DM: I did, and the course that John McPhee [’53] has long taught, and many generations now, later, have emerged into professional writing from McPhee’s Literature of Fact course, happened to be taught, the spring I applied for it, by Robert K. Massie, a biographer, which I suppose must’ve been some kind of clue that I ignored for a while, because what happened to me in the course was that I instantly realized that my notions of fiction writing, that I had developed in the creative writing program on Nassau Street, were somewhat inflated, or maybe I wasn’t so cut out that way. But there was a sense of paragraphs, and sentences, and commas that the literature of fact course gave me, almost immediately, a kind of almost plastic, tangible sense of words, and syntax, and grammar in a way that I’d never really encountered it before. And, as well, a kind of energy toward reporting and toward going out in the world and bringing back the goods.

And that course really changed my life. I remember doing reporting in a Superman-style telephone booth in Firestone Library in between classes, and getting incredibly excited and turned on by the idea that you could pick up a phone, in those days, and call anybody, anywhere, and get the story, at least part of it, and then begin to look through the stacks themselves. And it was just an incredibly exciting course, and time, and it projected me out into the world pretty fast, even more quickly, in some ways, than writing a book. And certainly, my thesis, which was a last stab attempt at fiction, also persuaded me that it was time to turn to nonfiction.

So, I entered the world of New York City journalism as a freelancer, and long story short, it was really the biography form itself that Bob Massie, whose work I had admired a great, great deal, that became my path and became the ultimate plan, really, for how to bring a lot of the different things that journalism couldn’t do into a focus, into a narrative that had a beginning, middle, and an end, and especially, an end. Fiction had always baffled me. I never knew how the end things. Whereas with a biography, of course, you know what the end’s going to be.

BT: The amount of work that goes into the types of biographies that you write is extraordinary. It’s years and years of work. What about that process appeals to you?

DM: Well, I don’t want to go too heavily on the Princeton of it all, but truly, the open stacks at Firestone Library were the beginnings for me of an actually uncanny sense — and I don’t want to get all mystical about it — but an uncanny sense that when you’re looking for something, things will actually come to your fingertips. I think you can, if you’re fairly intuitive, you can probably do it as an exercise yourself, just by walking down an open stacks — when you’re looking for something — letting your fingers find your way to things. You will find things there, and I think that you’ll go in an old fashioned card catalog search to a single book, and it’s always the books — this was a McPhee lesson, actually — it’s always the books to the right, the left, and up and down, and around it that draw your attention, and somehow, bring you deeper into the subject. And that’s always what it is for me, and always has been, and it really started on B floor, literally. And I think that style has changed because of the internet, which is now full of rabbit holes. It’s not just the books above, to the right and the left on that metal stack, it’s actually these extraordinary rabbit holes.

And my subject, Eleanor Roosevelt, created one of the biggest rabbit holes of all time, for me anyway, which was an unexpected one, which was that in the old days, of course, I would actually get literally seasick by looking at microfilm. Having to track something through a newspaper was a bit of a nightmare, and actually, it limited, I think, what you could do, and limited what you, physically — you just couldn’t, unless you were a complete freak, you couldn’t really quite get as far as you — nothing like today. Today — with Eleanor Roosevelt, there were at least 10 to 15 reporters covering her every day for different newspapers. And then, the wire stories going out to local papers across the country. But what I discovered on Newspapers.com and any simple, now — simple website like that, was that Eleanor could be seen in real time in ways that previous biographers and previous students and scholars wouldn’t have dreamed of being able to see her. And the detail was quite something, and also just simply to hear her saying things to reporters at the time that hadn’t made it into the final draft of history, so to speak, and were in the first draft of history, which would change inflections. And you’d hear her speaking in different ways, much more harshly, actually, often, and negatively about things.

She’d be asked about her husband having just been elected governor of New York, and she’d be quite frank, say, “It really doesn’t matter half as much to me that Franklin was just elected governor if governor Smith, Al Smith, running for president — if he’s not going to be president. It just won’t make that much of a difference to any of us.”

And so, to see her being that candid with reporters, all again, through this internet rabbit hole of Newspapers.com and others like it, was to see her anew. And that was really my project with Eleanor from the beginning, was to find a way to tell the life of Eleanor, not only in one volume, but to tell her clean, and to tell her in a way that was closer, maybe, closer to the way she had actually lived her life. That’s always the hope. It’s a great distortion biography, but it is the hope that you will find a new way of looking. And I think I did.

BT: And it’s extraordinary, not just that she was so broadly covered by the news, but that she wrote her own column, that she was, for many years, a syndicated columnist. How important was that for you to have that resource, and how important was that for her, to have that unfiltered connection with the American public?

DM: Those incredibly great, both really great questions, because it’s absolutely true. I think, actually, Eleanor Roosevelt, as she wrote “My Day,” which is what we’d now think of as a live blog, every day, 500 words filed at 4 p.m. It forced her to sit down and, every day, record how she had had — the thoughts she had had, the interactions she had had. But what it really did was it connected her — she asked people, when she first began, “Please tell me what’s on your mind. Please let me know. Please communicate with me.” And the letters would flood in by the hundreds of thousands. And that wasn’t really the connection. The connection was actually in her movement, in her mobility, and the velocity with which she got around the country, and the way — people came to the president, but Mrs. Roosevelt came to you. And she would connect with you.

She saw democracy as an active reciprocity. It wasn’t just about balancing acts of institutions. It was about how we treated each other. It was about how people understood each other in communities. And she took the theme of reciprocity and brought it to life, made it active, brought it into action. And the column was one way, actually, that she constantly, reciprocally, communicated with the reading public, which might seem as if it had been a limited one, but at the time, it was actually enormous. And for me, who had written a biography of Charles Schultz, and therefore began my days — my happy days, when I was writing that book, I’d read about 15 or 20 Peanuts comic strips first thing as I sat down. And it was through that process — which was actually a digital process, and therefore, I could do it in real time, and or I could search themes and subjects through a word search. But if I did it in real time, I began to see that actually it was a form of diary for Schultz. And actually, with somebody with a pen in their hand, and ink at the end of a nib, it is a — not a psychiatric or psychological exercise, but it’s certainly an act of self-revelation, because so much is under restraint in the form itself of cartooning in these four panels.

Eleanor was very similar, and in fact, really one of the places my book began was in the basement, strangely enough, of 200 Madison Ave. — the United Media syndicate, had been the United Feature Syndicate. And in 1950, that’s where Peanuts began. A small, round-headed kid appeared in the very first strip. And Charles Schultz, a young man from Minnesota, was the strip artist and author. He had sold this without any hope of it becoming anything more than something that would probably vanish quickly. And I was allowed to see, in the basement, these very early records of the first year. And as I came upon the banker’s boxes, in which were stored first Peanuts and all the correspondence that went with it, what was right next to it, alphabetically, R-S, was Roosevelt.

And I looked in, and I thought, “Oh, that’s right. Eleanor Roosevelt wrote a column.” And I pulled out one big, huge blue galley, and it — the first thing I read was a description of starlight from a sleeping porch, up in the Hudson Valley. And I thought, “Eleanor Roosevelt?” And then, the next thing was talking about the refugees after the war. And I said, “Well, yes, this sounds more like Eleanor,” but it kept varying, and I kept seeing that there was much more subtlety and nuance, and especially, observation. She was a first-class noticer. She observed and saw things that other people wouldn’t have, and that other people in public life tend not to, or tended not to, at the time.

What a great way to capture this sense of motion, because she was such an action figure. She left thousands of words, millions of words, there’s millions of documents, but my project, my book was — my attempt was to free her from the archives, and free her from the words, and to see her in action. And that was really always my essential litmus test as turning points and as events took place in the story. I would always try to find out, “What did she do?” Not what she said, or wrote, but — not the record she left — but what does she next do?

BT: And one of the things that comes through in the book is the effect that Eleanor had on the people she encountered. We may think of FDR as the charmer of the couple, but she also could make quite an impression. Do you have any favorite examples of that that came through from the research?

DM: Well, yes, two really good ones, and one’s general and one’s specific.

People thought of Eleanor Roosevelt — and I, in fact, encountered this frequently, even speaking to women, even women actresses and people who you would think would be far more sensitive about public presentation, and especially today — but people thought she was ugly. People had this illusion, and a myth that had been created around this illusion, that Eleanor Roosevelt, who had buck teeth and a — she herself, by the way, promoted this. She would often — she was very self-deprecating by nature. But a short chin, and buck teeth, and a face that often was at rest during a photographic session earlier in her life, or was stern, or was thoughtful. And so, she didn’t translate — she was literally not photogenic. There were — it was hard for her to have her picture taken.

When people, therefore, saw her in real life, they were stunned. First of all, they were stunned by her height. She was just under six feet. But the way she carried herself, shoulders back and slightly tilted forward, sort of in the almost the stance of a cross-country skier, and with great, loping strides — and people, even a 6’1” man like Ernest Hemingway, would see her and say — and would write down in his diary, “My God, she’s enormous. … What a remarkable woman.” And people would be floored by her eyes, and her eyes, which were taking in so much, but also were taking you in and seeing you and reading you. And she read people and read gestures and read faces and read expressions and microaggressions, micro-expressions. She was an early pathfinder in the world of microaggressions. And you actually see it in her writing, how closely she understood this, and how closely she understood it was a part of politics, and how tough her skin became because of it — what a strong hide she developed. But that’s another story.

In her presentation with people, they saw her seeing them, and they felt seen. And it happened time and time again. She made, of course, the point — one thinks of Eleanor Roosevelt as a kind of do-gooder, and as a schoolteacher on the move, telling you to eat your vegetables and do your homework. And that was all there, but what she was, in person, was a far more — far looser. Not informal, but everything about her flowed, and you felt a sense of flow and energy and transformation. And people felt literally transformed by her when they saw her, and when they met her.

It was, in a way, a transaction that allowed you to think you had something to give her. She looked into you and expected something from you. And a lot of people didn’t feel, at the time, that they would have something to give the first lady of the United States. Eleanor — you didn’t see people like that. People didn’t — there was so much less exposure. You saw Eleanor Roosevelt as a giant of the newsreels in your movie house once a week. You didn’t see her constantly on a little screen in your hand or on your desk. You saw her picture in the paper. You saw her in news. She was a figure of enormous reach and radiance. And people, when they saw this in real life, were moved and never forgot it.

The other encounter I wanted to mention was her own horror when she finally got permission to go to the South Pacific, as first lady, during the Second World War. And she had paid her own way to the West Coast, so as not to — no one could criticize her for using government funds to make at least that much of the trip. She got on a transport, and she went down and made an 18-day trip to the South Pacific, where men had been fighting and blood had been shed in ways that had never been seen or experienced by even U.S. Marines in warfare, in any warfare before. It was — the South Pacific war was something new. And Eleanor Roosevelt knew that she should be there, somehow, as she had been, but in other — going to hospitals, going to see troops.

The war had transformed her, too, and her job. And she donned a Red Cross uniform. She had been a co-director of the Office of Civil Defense at the beginning of the war. And each time she landed on one of the Pacific islands, when she arrived, men were waiting, hoping that Ann Sheridan, the “Oomph Girl,” or Betty Grable, or one of the pinup girls would appear suddenly on a plane. And then, off this DC3 would step a middle aged lady in a grass skirt — with a big smile — and they melted. They actually were thrilled. It was — she mirrored a lot of their feelings about home and mother, and there was a bond between Eleanor and her own sons that translated equally to the GI’s, that she then would see one by one by one, as so often in her life in public.

She made a point of stopping at every bed in each hospital in each of the combat zones, and not just white troops. She found the Japanese American troops, who were fighting as GI’s, as Marines. The American-born Japanese soldiers, who were absolutely as loyal and hard-fighting — and harder fighting — than any other man in the front lines of the Pacific War. But she knew that going to see them would be incredibly important.

She also wowed the generals, and Admiral Halsey and everybody else, who had doubted that she would do anything but make a softie, kumbaya visit. She was tough, she was gritty, she knew how to talk to men, and she knew how important it was for them that, “Where are you from, soldier?” “I’m from Muncie, Indiana.” “Oh, I know your town. I’ve been to your town. I remember …” and they would — and she connected in ways that no one had ever connected. And she did this all through her public life. And it was always a matter of the individual, always a matter of who was right in front of her.

BT: In contrast to the woman she became, Eleanor, as a child, sounds like someone who had a lot of trouble fitting in, particularly after losing both of her parents. How do you think that experience shaped her, and what was it about her childhood that made it so difficult?

DM: Well, it was made difficult by the fact, very simply put, she lost her mother, her younger — her older, younger brother, she had two brothers. And the older of which, as well as her father, all within 19 months, by the age of 10. By the age of 10, she was an orphan. And she had one younger brother, now, to look after. And she was sent, as an orphan, with her younger brother, to live under the care of her grandmother, with aunts and uncles who were all in an old fashioned Edith Wharton-like Hudson River and old New York family, that was down, coming very far down at its heels, and falling into itself, into addiction and alcoholism and disrepair and dysfunction.

And she became, out of these experiences of losing her parents and joining a family that was highly dysfunctional, she became a child adult. She became the Dickensian Little Nell-like figure, leading around those uncles and aunts, and taking care of them, and bailing them out when they were arrested and went before a judge. It was she who showed up with the bail money. It was Eleanor who became, without any way of knowing how to do this, but finding within herself increasing strength, and an ability to manage and to feel needed, and therefore useful, she had what we now call agency out of her own misfortunes and the dysfunction of her family.

And the odd thing is that when she met Franklin Roosevelt, her fifth cousin, he was in a very different place in his life. They were about the same age, but he was an only child, who had been coddled and swaddled and cared for by a mother who thought he was already president of the United States, and treated him like that. And there was nothing more executive and high-functioning and royal than Franklin Roosevelt. And what Eleanor and he both had, on the other hand, was a sort of compact — I always thought of it as a compact of oddballs. Because Franklin, for all of his supreme confidence and sense of place and sense of mastery from an early age, in the world, was not very comfortable, and was not very comfortable among young men in his peer group, and among people out in the world. [He] had to learn not to be the privileged, elite, snobbish, entitled young man, had to learn a lot of things about people and the world.

And Eleanor, who went much faster than he did into the world of settlement houses and social work and social justice, was an early influence on him in that area. But for both of them, it was the same throughout their lives. It was pain itself, it was the facing of pain, it was the understanding of pain, and not the running from or denial of pain, that allowed them to become people who could translate their own pain into public good and into public service.

BT: One thing that I think really drives your book are these fairly intense periods of inspiration in Eleanor’s life. So, I’m thinking of, first, her time at boarding school, where she finds her voice, working for the Red Cross during the First World War, later on, exploring rural poverty during the Depression. Do you see a common thread in the things that inspired her, the things that she was most passionate about?

DM: Yes. I think it’s the sense that if you can do something for one person in a community, if you can do something for a single cause, you will find a way to expand that outward. I’m thinking now of Arthurdale, the homestead community in rural Appalachia in West Virginia, that she — was not a great success in its building, because there were all sorts of problems, actually, slips between the government and the actual creation of the town itself. But what Eleanor did was she did raise private funds. She raised government money. She used New Deal energy and New Deal sources to create, for people who lived in a town where there had been nothing, create a sense of purpose and a sense of community and a sense of reality that was long-lasting, far longer-lasting than when we think of these homestead communities in the New Deal. They seemed to be temporary. They actually lasted a lot longer than we originally thought. And I think what she created always with these was a sense that this can be done, and if this can be done, then something else can be done.

And that sense of building and building blocks to wider and wider is why you see somebody going from, in her own life, from a woman who thought she literally would never be able to speak a sentence in public, to becoming, through a wife of a government official in Washington, D.C., the first lady of New York state, the first lady of the United States, the first U.S. Representative of the UN, to becoming the chair of the commission that created a document, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, that went to all communities, and all nations, and asked all people to agree — 18 nations on the drafting committee — what are human beings, what are their rights, what does belong to them in their communities, what does belong to them, and how can we state this in a way to prevent anything happening to individual human beings the way it’s just happened to six million in the Holocaust. The way it’s just happened to 19, 20 million casualties in this war that’s just been fought — how can we prevent war. So these — to go from the micro to the macro is the continual arc of Eleanor’s life. And I think that there’s a certain fearlessness there that is required. I sometimes think, “How is she going to do it, really? How is she going to do this this time?” She is in no sense qualified and knows it, and yet, would always trust an inner strength, something that she could trust in herself.

She was often criticized in her own life, or people would say, “It’s only because of being married to the president of the United States. It’s only been because Franklin Roosevelt was a four-term president, and one of the greatest politicians of all time, that she could do what she did.” It’s really not true. And it’s not only because I’m seeing it from her point of view, but she truly was a far more evergreen person, in a way, even than her husband, because she kept growing.

BT: And as a result of that, on certain issues, she was much more progressive than her husband, I’m thinking of the anti-lynching legislation, and internment of Japanese Americans. When things that she believed in were not moving forward, how did she deal with that, particularly when the person who could move them forward was her husband, and he was choosing not to?

DM: Yes, both those are two shocking — it gets shocking as you see often — also how long it went on, how long Franklin Roosevelt had the stranglehold of the Southern Democrats as part of his coalition and part of his New Deal legislation, the needs for his New Deal legislation. And you see how he would not take a stand on lynching. And you see him, as Hitler made clearer and clearer what was going to happen to the Jews of Europe, and how refugees began appearing, how little Franklin Roosevelt, how little he responded at first, how he even called the Evian conference, and didn’t go himself. That was to deal with the — what was going to happen to refugees. Yet he himself would not show up. And of course, worst of all, an executive order putting Americans — American-born Japanese owners of shops and owners of property, and owners — and people with businesses all throughout California — into concentration camps.

Eleanor’s response to that is extremely telling, partly because she was in a position, in the first flush of paranoia and horror and panic that gripped California and Californian officials — she herself was a government official at the time, the co-director of the Office of Civil Defense — and flew directly to the West Coast. And as she made her way, as a government official, soothing and calming and doing all the things that you think of Eleanor Roosevelt doing right after the bombing at Pearl Harbor, she also met with Japanese American groups. She tried to calm fears. She tried to hear and listen and let them know that there was somebody in Washington who cared about them. And it was a — at the time, I think, probably, as important as anything anybody else was doing. I think it became more important when, actually, the camps were established, and unrest and rioting broke out at the Manzanar Camp. And FDR, not knowing who else could do the job, sent Eleanor Roosevelt, sent his wife to the Manzanar Camp. And she did bring at least some rest and calm to the situation, but was always struggling against the policies, and struggling against the politics that her husband was either making a terrible mistake about — and she had no compunctions of telling him so, and he had no compunctions, actually no problem, with hearing her say so.

I have to say, one of the things I love best was finding all the times, during the presidency, where she would say to him, “Tomorrow, I’m going to write about X or Y, this controversial subject, that controversial subject, in my column. Will you have any problem?” And he’d say, “No, you go ahead. You write what you need to write, and if anyone criticizes me, I’ll just tell them I can’t control you.”

And they had a nice way about that, and standing shoulder to shoulder and facing the world together. He did support her. He would use Eleanor in ways that I think she recognized that she was being used, in a sense. But he also really — he deeply respected what she was doing, and recognized that without her, a lot of things wouldn’t be happening in the Roosevelt administrations.

BT: By the end of her life, she was a heroic figure, an inspiration for a generation that was just coming to power in the ’50s and ’60s, women and men. What do you see as Eleanor’s legacy today? Not just among first ladies, but in the world at large?

DM: Human rights is without question the concept that became because of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The document itself — although it did not become part of U.S. legislation, although it did not become the basis for treaties — it became the touchstone, the lodestar, the North star for how we would shape foreign policy for over 50 years. Human rights was on the agenda right up until four years ago. It is on the United States agenda, the agenda of the world’s greatest democracy, at the time, we thought. And today, we have doubts, I think, partly because our human rights, our record on human rights, is so compromised. Eleanor is equated with a view of human rights that is as universal as you could ever imagine it being.

She also is seen, I think, as somebody who brought to the individual their own duty to their government, to citizenship. How are we going to treat each other and how is democracy going to be reciprocal, not just for those in power, obviously, and those in the ruling and educated and corporate classes, but for the least among us. And I think, when people talk about caring for communities, and caring for people, neighbors caring for the elderly, caring for minorities and those who are struggling at the lower ends of society, there is an Eleanor Roosevelt legacy that you see a lot. It’s alive in people, and alive in people who are doing things, being active, and staying in a fight that will go on, and will go on because — as she herself recognized, and we now see actively — democracy isn’t a solution. It is an ongoing struggle. And I think she embraced that struggle and embraced the unfinished-ness of it.

BT: And I gather — a footnote — your mother worked on Eleanor’s public television show in the late ’50s, early ’60s. Do you remember meeting her?

DM: It’s one of my earliest, and dimmest, but earliest memories. And it’s dim because it’s so limited, but it was literally another day just before air time at the WGBH makeshift studio at Brandeis University. Eleanor Roosevelt would pour tea and sit at a table with young Senator Kennedy, young Henry Kissinger at Harvard, young people, young Hubert Humphrey, a guest from Ghana, a guest from the Soviet Union. And they would have a roundtable discussion.

So, that was all just about to air. And I was a 4-year-old child whose mom had somehow unleashed him onto the studio floor, where I looked up and saw this figure of — I remember a nimbus of white hair — and I thought to myself, in no logical way, that I simply blurted out what I wanted when I saw this person, as everyone did with Eleanor Roosevelt. Everyone asked her for something. And I did, too. And I asked her, as my memory tells me, for Juicy Fruit. So, I asked for a stick of gum, and what I remember her — the only continuation of the memory is that in some part of her response, she bent down. And as she did bend down toward me, from her eyes, from her face, literally poured light, a sense of — I, literally, felt a sense of goodness coming from this person in her amusement and merriment at this little boy asking for gum. But I did feel that at 4 from Eleanor Roosevelt. And that’s the extent of the memory.

BT: Well, David it has been great speaking with you about the book. I really appreciate it. Thank you for joining me.

DM: Thanks so much, Brett. It’s really a pleasure.

BT: If you’ve enjoyed this podcast, please subscribe and visit our archives on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Soundcloud, and on the Princeton Alumni Weekly website, paw.princeton.edu.