After Princeton, Suleika Jaouad ’10 moved to Paris, where she was joined by a new boyfriend, worked as a paralegal, and dreamed of covering global conflicts as a journalist. Her plans were disrupted by a different battle: At 22, she was diagnosed with a rare form of leukemia. Back in New York City, she underwent chemotherapy, a bone marrow transplant, and yet more chemotherapy. During four years of treatment, she was frail, bald, isolated, and often in excruciating pain.

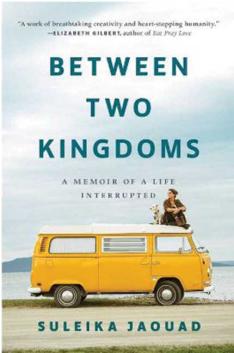

Although she was given only about a one-in-three chance of survival, she is now cancer-free. Her story — of grief, hope, loss, resilience, and a search for community and meaning — is chronicled in her new book, Between Two Kingdoms: A Memoir of Life Interrupted (Random House). It is dedicated to friends “who crossed the river too soon.”

“I feel very grateful to have attained the ranks of those who are cured,” says Jaouad via Zoom, “although it doesn’t come without its challenges. There’s so much collateral damage that comes with illness, and the most treacherous is so often the invisible kind.”

Her book’s title borrows from a Susan Sontag essay, “Illness as Metaphor,” describing, in Jaouad’s words, “how we all have dual citizenship in the kingdom of the sick and the kingdom of the well.” After her long illness, Jaouad says, “I hoped to be repatriated back to the kingdom of the well. But the distance that you have to travel between those two — that’s often overlooked.”

The book’s subtitle refers to a column and Emmy Award-winning video series, “Life, Interrupted,” that Jaouad produced for The New York Times. “I decided that I was going to report from a very different conflict zone — my hospital bed,” she says. The project gave her purpose and elicited an overwhelming response from people whose own lives had been shadowed by mortality, including a high school teacher whose 26-year-old son had committed suicide and a convicted murderer on Texas’s death row.

“Illness has a way of narrowing your world,” Jaouad says, and the letters she received “blasted the world wide open.”

But in the aftermath of treatment, she struggled. Her relationship with her boyfriend had collapsed. She felt “unsafe in my body” and “terrified of the outside world.”

Between Two Kingdoms chronicles two distinct journeys: Jaouad’s trek through sickness and the 100-day, 15,000-mile transcontinental pilgrimage, with her rescue dog Oscar, that she undertook in its wake. After learning to drive, she set out to meet some of her correspondents and learn how to reconstitute her life.

Jaouad’s book proposal had focused on the love that helped save her. The book “is still about finding love,” she says. “It’s also about losing that love — and about loss in general, the loss of identity, the loss of a life as you knew it, the loss of fertility, and of a certain kind of invincible certainty.

“But it’s also about how, when you have an experience where everything you knew to be true gets upturned, there’s a kind of brutal discovery, when — in the aftermath of that loss — you have to figure out who you are and where you’re heading.”

She encountered strength, wisdom, and unexpected commonalities on the road. She learned, for instance, that she and Lil’ GQ, her Texas death row correspondent, had both spent long hours of confinement playing Scrabble — in his case, by using scraps of paper and calling out moves to other prisoners. “I was so awed by his creativity,” she says.

Since her trip, Jaouad has had an active writing and speaking career, distilling lessons from her illness and recovery. In June, she earned an M.F.A. from Bennington College. She has launched a “community creativity” project, The Isolation Journals, which supplies weekly writing prompts to about 100,000 people. She also is developing a podcast, The Reckoning, about “moments of great reckoning, good and bad.”

Jaouad lives in New Jersey with her partner, Jon Batiste, a renowned jazz musician whom she met at band camp when she was 13. Still immunocompromised, she stays semi-isolated, socializing only with a small “quaranpod” of friends.

“We inherit resilience,” she says. “Our ancestors had to survive all kinds of things for us to be here. But I also think of resilience as a muscle that you have to exercise. There were so many points in my illness when, for example, I found out I had to do more treatment or undergo some painful procedure, where I thought, ‘I can’t do that — not one more thing.’ And yet I did. We’re all, right now, because of the pandemic, having to exercise that muscle of resilience.”

In her own life, she says, “everything is in technicolor. I say in the book that illness gave me a jeweler’s eye. That clarifying effect when you’re staring your mortality in the eye — as terrifying as it can be — also forces you to refocus your gaze on what really matters when everything else is stripped away. And I wouldn’t take that back.”