From Art to Innovation, Campus Was a Summer Hot Spot

Despite the intense heat and mass exodus of Princeton undergraduates this summer, the campus hosted many students who learned how to do everything from design thinking to coding to making art through a variety of programs, including several with expanded offerings this year.

Those who lived on campus took part in the University’s second annual Summer Research and Learning Village, which housed students in neighboring (and air-conditioned) dormitories and held events such as career development sessions and trips to New York City. The following vignettes capture the experiences of participants in three of the programs that brought students to Princeton.

Rising to the Challenge of Natural Disasters

When the Keller Center’s revamped Tiger Challenge program kicked off at the beginning of June, no one, not even Jessica Leung *19, design program manager and a lecturer at the University, knew what the summer would entail. That’s because it was up to the seven enrolled students to come up with a solution — or in their words, an intervention — to a community problem.

Leung believes the Tiger Challenge, a human-centered design thinking program focused on taking action, is a step above community service, as the goal is not only to create a big impact, starting at the local level, but also to empower students to take part in the creation process.

For the first time, this year’s summer students tackled a full design cycle — starting with understanding a problem before conceptualizing an idea and then piloting an implementation — rather than handing a project off to those enrolled in the Tiger Challenge course during the academic year, as has been done in the past. And they only had nine weeks to do it.

The students first met with several municipality employees to hear about pain points in their work before solidifying a connection with the director of emergency management, Michael Yeh, who asked for help improving disaster preparedness and community connection in Princeton.

Yeh appreciated the extra sets of eyes and feedback as the students combed through the then-current information available to Princeton citizens, like whom to call when the power goes out or what to do in case of a flood. They found that some important information was difficult to find on the municipality website, especially for populations who may not be as familiar with available resources, such as elderly residents who aren’t comfortable with technology or migrants who don’t speak English.

“For me personally, it was a very satisfying experience to engage with these very motivated, very intelligent students,” said Yeh, who added that professionally, he benefited from “taking information that they were able to glean … to find out what the audience is understanding.”

Leung said the students acted as a bridge between the municipality and the community, because “the people are not doing what the municipality expects them to do.”

To fully comprehend the issue, the students immersed themselves in Princeton by setting up tables in high-traffic locations like farmers markets and local grocery store McCaffrey’s to encourage discussions with passers-by. They also conducted interviews with municipal employees and federal officials and toured sites such as a Federal Emergency Management Agency base.

The group, which included students from a variety of majors such as economics and engineering, then brainstormed and continuously iterated their ideas. Leung acted as a guide for the students but left the rest up to them.

“I never actually know what we’re going to end up with because it’s really the students’ own interest and expertise, and what they know how to do,” said Leung.

They showed off their final product — an emergency go-bag dubbed the Princeton Prep Pack — to University administration, members of the police, and local officials at a first-of-its-kind presentation in July.

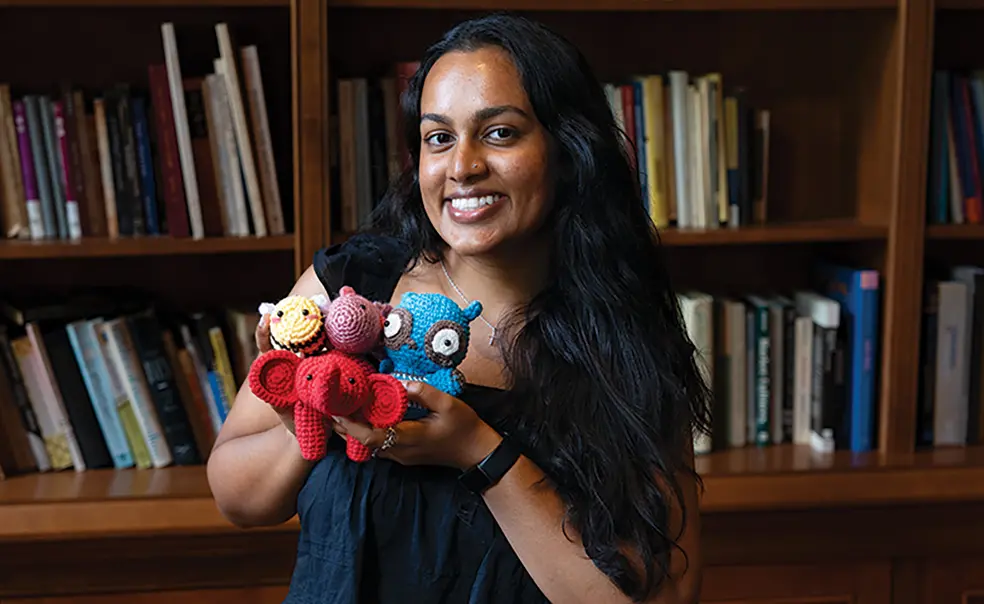

Katya Grygorenko ’27, an operations research and financial engineering major, acknowledged that emergency preparedness packs are not new but said their idea stands out because of the nontraditional items they chose to include that provide a “feeling of comfort, the feeling of connection,” such as small animal mascots the students crocheted and 3D-printed. The pack also includes a custom magnet that encourages users to share contact information with their neighbors so they can rely on one another in an emergency.

The experience made Grygorenko realize “that people are, they should be, at the center of our endeavors, and our inventions should be very oriented to reality and the situation at hand.”

Architecture major Julianne Somar ’26 felt empowered to create “something real,” and added that the group was “able to go from nothing to something in seven weeks, which was crazy. I’ll be talking about this for a long time.”

The final two weeks of the program included time for reflection.

Leung said organizers at the Keller Center, which works with the Program for Community-Engaged Scholarship, realized there was previously no “urgency to complete something in the summer or to get to some sort of tangible outcome,” so the goal was changed.

“These problems cannot be solved by a group of students in nine weeks. It takes years and decades,” Leung said. “But if you could move the dial just by a little bit, that is going to [start] a snowball effect.”

The group hopes the municipality will identify a funding source to produce the packs. Yeh said they may look to grants or sponsorships.

Coding, Computational Biology, and Confidence

Before enrolling at Rutgers University as a computer science major, Wali Palmer, a 45-year-old Camden resident, had zero knowledge of computers. He’d spent 25 years in prison, and around the time he was released in 2023, he decided “the best and fastest way for me to get on track and try to develop a better understanding of computers and technology was to just go for it.”

He spent this summer coding at Princeton as a Prison Teaching Initiative (PTI) intern and found the campus to be “like a breath of fresh air.”

PTI has offered paid competitive internships at Princeton for formerly incarcerated students who are enrolled at two- or four-year institutions since 2017, but the coding internship was a new addition this year. Other interns worked on campus in computational biology — funded by the National Science Foundation — and with the Emma Bloomberg Center for Access and Opportunity as part of the Aspiring Scholars and Professionals cohort, which focuses on the humanities, social sciences, communications, and education.

Throughout nine weeks, this year’s 12 interns had access to Princeton resources, such as the gyms and the library, and some lived on campus. Jonathan Wrenn, a 24-year-old New York City resident who worked with Claire Gmachl, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Electrical Engineering, said walking around campus and exploring the nearby nature trails made him “feel like you’re not trapped in a box.”

A high school dropout, Wrenn didn’t believe college would ever be in the cards for him, but he decided to make a change while behind bars to honor his grandmother’s final wish. He’s now a student at Columbia University and expects to graduate in 2026.

“I’ve really enjoyed the work I’ve been doing this summer. I think it’s going to be very applicable to my future professional endeavors and maybe even possibly conducting research at Columbia,” he said.

PTI staff make a conscientious effort to ensure “our environment supports the sense of ‘I do belong at Princeton,’” according to Jill Stockwell *17, director of PTI. For example, at facilitated weekly lunches, the interns tackled topics such as imposter syndrome and resume-building.

Through a pilot mentorship program, some interns also connected with Princeton alumni from the Class of 1994, which began a partnership with PTI in 2019 for its legacy service project. Together, PTI and the alums collectively decided “wouldn’t it be great if Princeton alumni would open up their proverbial Rolodexes, would reveal the kind of skill sets that they saw as making you successful within their industries, 25, now 30 years into their careers,” said Stockwell.

Ali Muslim wanted to become a motivational speaker, so PTI matched him up with Rusty Gaillard ’94, who for many years was the worldwide director of finance at Apple and is now an executive and career coach. Muslim first came to Princeton as an intern for the ASAP program in 2022, then for computational biology last year, and is now a program assistant for internships at PTI.

Gaillard said the mentorship is “a commitment and it’s time and energy, but I get back so much more than I put into it, just from the inspiration and the connection with people who are making positive steps in their lives.” He added that “it’s just wonderful to see and have a small role in that.”

Through conversations with Gaillard and self-reflection, Muslim realized in addition to his motivational speaking goals, he also wants to open a nonprofit for youth and attend graduate school. He graduated from Rutgers-Camden earlier this year with a bachelor’s in psychology and was chosen as a student speaker for Commencement.

At the ceremony, Muslim explained that at age 16, he was sentenced to serve more than 35 years in prison, which made him lose touch with his sense of self-worth. But now, thanks in part to being embraced by the academic community, he feels he has been given a second chance.

Noting that he “proudly represent[s] students who come from incarcerated spaces,” Muslim said in his remarks that “it’s been a long journey for me to get to this point.”

Stockwell said everyone who teaches with the PTI program “says it’s the best teaching experience of their life,” because the students are “mature adult learners” who apply their life experiences to their learning.

PTI’s success led to a 2019 grant from the National Science Foundation to STEM-Opportunities in Prison Settings (STEM-OPS), a network of organizations aiming to improve STEM learning for those who are currently or formerly incarcerated; PTI is one of five founding partners. As part of the grant, PTI staff produced a national toolkit that highlights some of their most effective strategies and approaches that other universities can use to build their own internship programs. It launched earlier this year and can be found at stem-ops.org/internship-toolkit/.

High Schoolers Master the Art of Art

The new Princeton University Art Museum is still months from its grand opening, but that didn’t stop 12 high school students from learning how to create and curate art at the University this summer.

For the second year, museum staff piloted its Summer Academy for students in the greater Trenton area who are interested in careers in the visual arts and in museums. The three-week program included talks with a conservator, a lighting designer, art handlers, and curators, as well as several days with teaching artists, and concluded with a show at the Art on Hulfish gallery, where students spoke about their pieces — chalk paintings, graphite and charcoal sketches, collages, and videos — in front of about 50 family, friends, and locals.

The museum has long offered school tours to children in kindergarten through high school, and has programs for undergraduate and graduate students, but Brice Batchelor-Hall, the museum’s manager of engagement, said this program exposes the soon-to-be-adults to art-related career paths.

The students spent half of their summer discussing and learning about art and art careers and the other half making their own art. Assignments included drawing their own hands and some of their favorite objects.

This year, the students’ work and group discussions centered around the themes of identity, power, and social justice. Raven George, a conceptual artist based in Trenton who worked with the students for several days, said, “When you actually take the time to sit in those emotions, you find the beauty in your work.”

George encouraged the students to really study an object or setting prior to putting pen (or pencil or chalk) to paper — “it was really beautiful to watch [the students’ progress]” she said — and they also practiced close looking at pieces in the museum’s collection that fit the chosen themes.

Batchelor-Hall was touched by how vulnerable the students were in exploring “things that they are struggling with in their own lives that they put into their artwork.” She believes the program “was an opportunity for us to celebrate their voices.”

According to Batchelor-Hall, the academy, which was free and included transportation to and from campus, is part of the museum’s commitment to “the next generation of museum professionals” as well as building “relationships with our neighboring communities.”

Museum staff partnered with Dawn of Hope, a nonprofit that empowers girls from underrepresented populations, and Sprout U School of the Arts in Trenton for the program.

No responses yet