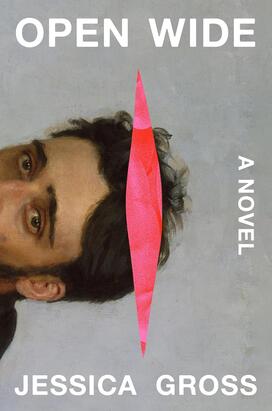

Jessica Gross ’07 Explores Awkwardness of Intimacy in New Novel

The book: Olive is weird. She has a hard time connecting with others, which has become painfully obvious as a single 30-year-old. As a form of practice and way to understand social cues, she begins secretly recording conversations, hoping to break free of her lonely struggle. Then one day she meets Theo, a surgeon fascinated with organs. He’s as weird as Olive and she feels an instant connection. Open Wide (Abrams Press) explores the human experiences of love, intimacy, and the body, and what happens when they are pushed to the extreme.

The author: Jessica Gross ’07 is a novelist and essayist who earned her undergraduate degree in anthropology at Princeton. She is the author of Hysteria and Open Wide, which have both been picked up for screen adaptations. Her nonfiction work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine and The Los Angeles Review of Books, among other publications. Gross has also taught fiction and nonfiction writing at The New School in New York and Texas Tech University.

Excerpt:

Part One: Meeting

It was on one of those unreal early-summer days, the window boxes violently in bloom, that our merger began. As I walked, I ran my digital recorder as I did constantly, collecting sounds the way other people collect stamps. A bus hissed and screeched. Someone yelled, “Yo! Shithead!” Playground swings creaked on their hinges. A dog retched and a child cried out, “Tata bawfed!”

A woman approached, icy blond, with a face cut into impossible angles and shrouded in a pair of oversized hexagonal sunglasses. Her shapeless shift dress still revealed her tininess. As she passed, and I pointed the recorder toward the ground to pick up the clack of her derbies on the concrete, I watched her chew a wad of gum as though it had affronted her. It was too bad I couldn’t hold the recorder up to her mouth. You can tell a lot about a person from the way they chew their gum. Her jaw worked in circles, her lips parted — every so often she’d crack it against her teeth, just the way the popular girls in high school used to do it. She was probably loved. Her footsteps receded. She hadn’t even looked at me.

The route to the food pantry where I volunteered took me past a restaurant with sidewalk dining, where couples and girlfriends brunched with grating merriment. People squealed greetings over the clanking din of forks and knives, and one blessed diner said, “I want to eat her face.” A hacking cough wafted from an open window. A teenage couple strolling hand in hand tried to kiss while walking, then laughed when they missed each other’s mouths.

As I watched the two of them, I regretted having made myself look as crappy as possible. I had, I admit, begun volunteering in hopes of meeting a man. Throughout my 20s I’d tried various gambits: I’d gone to open houses for expensive apartments across downtown Manhattan (I only met one man who was single, who also repeatedly used the phrase “right on”); reserved a seat in the movie theater next to an open spot on the aisle, hoping it would be claimed by a solo moviegoer; brought a book to my neighborhood bar. Failing to strategize, I brought the novel I actually happened to be reading —Tessa Hadley’s Late in the Day, a tender exploration of marriage —which, at the bar, two different women interrupted to tell me they’d loved. On my next attempt, I instead brought a book on the history of geometry that I’d received from a coworker; an excitable older man approached me to explain that the ancient Greeks had written the firstever mathematical proofs. (I knew this, as I had just read it.)

While these forays were unsuccessful, they made for entertaining stories at my expense. “Why don’t you try crashing a funeral?” my oldest sister, Romi, asked. “I hear tons of people meet at those.” I laughed along. She’d been with her husband since college.

By my 30s I had figured out that volunteering gave me the best chance yet of meeting someone kind who liked other people, qualities I’d recently decided to prioritize in a mate. And unlike fake apartment hunting, which left me feeling desolate, ladling out food at a soup kitchen or reading bedtime stories to children at a recreation center was a really nice way to spend time. For a few years I’d hopped from one New York Cares opportunity to another, but early in the summer, I’d lucked into a gig at a food pantry not too far from where I lived. Unloading cans and packets onto the shelves had a lulling rhythm, the mostly consistent group of volunteers had a casual intimacy that I slipped into without too much difficulty, and the guests who came once we’d fully restocked the shelves became familiar to me over the weeks, lending my Sundays the pleasurable comfort of returning home.

Today I’d dressed ugly, in some hometown youth choir T-shirt that someone had left in one of my college dorm rooms and cutoff shorts I’d made from a pair of baggy jeans, as if to prove to myself that I was really volunteering because I was so selfless, or perhaps to forestall disappointment. My singlehood had been a nearly lifelong era, punctuated by rare, swift romances. Mostly I’d lusted from a distance. At middle school sleepovers, I’d begged my friends to tell me everything about what kissing felt like, how the two sets of lips moved against one another, how each person knew which way to turn, what another tongue felt like in your mouth. As we got older, even before I’d kissed anyone, I’d had friends giving blow jobs, and I needed to know all about that too: what penises looked like, how they tasted, how hard “hard” was, what to do with your lips and teeth and tongue. Was it true that boys’ pupils got huge when they were horny? Was it true that when boys jiggled their legs, it meant they were trying to conceal a boner? I dreamed of pressing my whole body along the length of a boy’s. Yet whenever one was interested, I found myself running away.

My adulthood, too, had unfurled in long dry spells of yearning. It seemed to me I could never really access men, but perhaps it was that I found it hard to let them access me. It was still that childhood compulsion to flee. I worried at times that I was incapable of being in a relationship that lasted longer than a month or two, or that there was some secret part of me, deep inside, that wished to be single forever. Was my discomfort with dating possibly a discomfort with any sort of exposure at all?

Maybe this is why I was drawn to radio—because it offered intimacy with parameters, and at a distance. Not only that, but at work, I was in control: the intimate revelations came from my subjects; my only role was to elicit their confessions. Even recording people on the sidewalk or in casual conversation, then listening later to the tapes I’d made, was a way of marshaling chaos into order, and winning for myself after-the-fact dominion.

Usually I listened to my recordings all the way through, playing them while I was washing the dishes or folding laundry or cooking, as though they were podcasts. My intent was, at least in part, to amass a library of sounds: If I came across tape I could thread into a radio piece as background noise, I would jot the timestamp down in my phone or in my little red notebook, if it happened to be near, and bounce the clip later on. With these kinds of recordings—street noise or restaurant din or laughter in a park—I had no problem excusing my habit, given that it was for work, and besides, it wasn’t hurting anybody. It seemed far more innocuous than taking photos of strangers with a smartphone and posting them all over the internet. The be-derbied woman I’d taped on the street would be none the wiser.

Secretly recording my everyday conversations, though, was another matter. I tried to convince myself that this practice, too, was a necessary or at least helpful part of my job. Years earlier, my voice—more nasal on tape than it sounded to me in life—had made me wince, but I’d used the recordings to work on my speech, to deepen and round it, to make it more professional.

But I didn’t just use the tapes for work. I also scrutinized my social performance, noting missed opportunities for bon mots and practicing retorts, and studied details my friends had shared that I could refer back to in later conversations. As a result of this strategy, I’d been told on multiple occasions that I had a “very impressive memory.” I stored up successful conversations to listen to as company later, fights as potential future ammunition. (I’d never played back a tape of a conflict to prove anything, and promised myself I never would, but I didn’t delete them, either. They were my rainy day fund, and having them around gave me solace.)

And ultimately, I just couldn’t stop myself. It was something I’d been doing since I was a child, and I felt no more capable of quitting it than a binge eater does ice cream. I reasoned that, unlike with my tapes of street noise, I never used my recordings of conversations for anything; they were entirely private. Even if I’d wanted to use them for a radio piece, the sound quality of voices recorded from my pocket wasn’t anywhere near good enough. I’d need to place the recorder in plain sight, as close to whomever I was talking to as possible, to mitigate the interference of background noise. So what could be wrong?

Excerpted from Open Wide by Jessica Gross. Copyright © 2025 and published by Abrams Press. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.

Reviews:

“Sexy and smart, Open Wide is a modern fairy tale about obsessive love. Jessica Gross is a storyteller of extraordinary ability. The end is stunning.” — Luis Jaramillo, author of The Witches of El Paso

“Bad boundaries have never been so uncomfortably delicious, and Jessica Gross goes all in. This clever, provocative tale of the dream and horror of closeness has guts — a lot of them. Climb inside!” — Megan Milks author of Slug and Other Stories

No responses yet