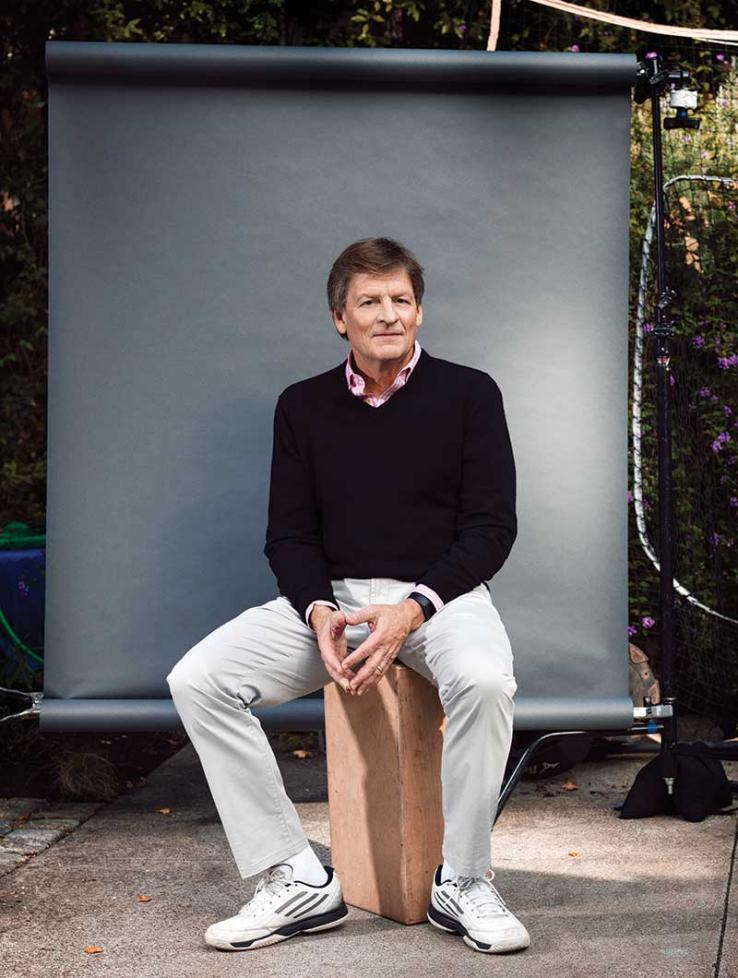

Michael Lewis ’82 lives to tell stories, so consider this one, about his latest book, The Premonition: A Pandemic Story:

It was January or February of this year, and Lewis was on a four-hour car ride across Southern California with Charity Dean, the public-health officer who is a central figure in the book. Lewis was reporting in his usual fashion, conducting one of his countless hours of interviews. On days when he wasn’t with Dean in Santa Barbara, he might be across the bay from his Berkeley home, talking to Joe DeRisi, a microbiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, who also figures prominently in the book. While most Americans were hunkered down, Lewis was still in the field — masked, of course. Zoom calls were reserved for sources who were too far away to justify the time and expense of travel.

“I had this false sense of security,” Lewis admits, “I think because I was spending all this time with doctors who are experts on the subject. Now that is a very bad idea to be running around with, but I had this idea that Charity Dean is not going to infect me, she’s a local health officer! Joe DeRisi’s not going to infect me! So I was spending a lot of normal social time with people on the false premise that doctors couldn’t make you sick.” Lewis punctuates this disclosure with a loud laugh that resonates through a Zoom screen. (PAW, unlike Lewis, was still working remotely in the spring.)

Lewis would turn the book — his 16th — around quickly: He submitted the final manuscript to his publisher, W.W. Norton & Co., March 15, and The Premonition hit the shelves less than eight weeks later. But if he had been certain that his collaboration with Charity Dean would turn out well, Dean wasn’t so sure. In the car with Dean, Lewis mused about the relationship they had developed. Isn’t it strange that we met nine months ago and now there’s going to be a book? he observed. What have you made of all this? For a moment, Dean was silent.

“I remember having the thought around September that nothing about your process inspires confidence,” she finally replied. (“And she was not joking,” Lewis says, with another laugh.) “You don’t record the interviews, you’re writing them down and then you can’t read your own handwriting, and you ask me the same question over and over again. I’m a doctor, a scientist. There are usually procedures for things, and I’m watching you — and you’re like chaos.”

Chaos, if that is the right word to describe his writing and reporting process, has worked very well for Michael Lewis. Serendipity would be a good way to describe the results. Lewis’ work regularly appears on bestseller lists, and he has twice won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Three books — Moneyball, The Blind Side, and The Big Short — have been made into movies.

“Michael Lewis has an uncanny sense of story,” says New Yorker editor David Remnick ’81. “He becomes curious about a world –– and it can be high finance or baseball or anything at all –– and he knows precisely how to go about locating a story within that world and then casting that story. In that way, he is like a great movie maker, but he is working with the stubborn material of facts.”

“He comes across as the kid who has stuck his thumb in a pie, come out with a plum, and wants to tell you about it,” notes Starling Lawrence ’65, Lewis’ longtime editor.

On May 25, a day after Lewis’ first interview with PAW, tragedy struck what in many ways was a charmed life, when Lewis’ daughter Dixie, 19, and her boyfriend were killed in a car crash near Truckee, California. “We loved her so much and are in a kind of pain none of us has experienced,” Lewis and his family — his wife, Tabitha, and Dixie’s siblings, Walker and Quinn — said in a statement to Berkeleyside, a community news site. “She loved to live, and our hearts are so broken they can’t find the words to describe the feeling.”

During a follow-up interview with PAW in late July, Lewis spoke about the tragedy. “For six weeks, nothing was of interest,” he says of the period following the accident. “I didn’t even taste my food. That’s now starting to change.” Determined to push on, Lewis recently completed scripts for the third season of his podcast, “Against the Rules,” in which he looks at changing conceptions of fairness in American life, and has also worked on the pilot for a TV drama. Although he has not yet decided on the subject of his next book, he says, “I think I will be able to write.”

In the fragmented world of modern publishing, there are two broad types of readers, observes Christopher Beha ’02, the editor of Harper’s Magazine: those who want to learn things and those who want to be moved by a narrative. Lewis, he says, is “incredibly good at appealing to both of these readers at once, finding characters who can also stand in for a larger story.” As an example, Beha cites Billy Beane, the failed baseball prospect who became general manager of the Oakland Athletics and helped a perennially underfunded team win games by identifying players who excelled at little skills, such as drawing a walk, that were undervalued in more conventional statistical analyses.

“We all take for granted now that Billy Beane is the central figure in the story of the revolution in baseball analytics,” Beha says, “but that is because Lewis made him one. His books are character-driven, but in the process you also learn something. What he does is deceptively hard, but he makes it look easy.”

Lawrence, who knows Lewis’ work better than anyone, acknowledges that last point. “Michael does not do the Suffering Writer very well,” Lawrence admits. “There’s no apparent stress.”

Judging from his quick turnaround time, words come easily to him. To ease his publisher’s anxiety, though, Lewis did submit drafts of some early chapters of The Premonition as he wrote them. But he completed it in about the same year-long period, from meeting the main character to final manuscript, that it took him to write most of his other books.

Asked how he beats writer’s block, Lewis explains that, first, he doesn’t believe in it. When he gets stuck, he just keeps writing, putting down sentences even if they might be bad ones. He can always fix them in a subsequent draft. What’s important is to keep moving ahead.

So Lewis is able to approach a challenge as great as developing a book during a pandemic and spot the bright side: Most people were stuck at home, so they were easier for him to reach. Also, all the small demands on his time were absent. “I had the most concentrated, distraction-free writing experience [on The Premonition] since I wrote my senior thesis in the bowels of McCormick Hall,” Lewis says. “I find that I get my greatest moments of exhilaration when I’m writing when it’s just me staring at a wall, no one else in the room, nothing else to do that day, no phone calls coming in, just total silence. And I had long stretches of that.”

“The pandemic,” he laughs, “made writing easy.”

In many ways, The Premonition is a quintessential Lewis book. Nick Confessore ’98’s assessment in The New York Times — “His subjects here are Cassandras: blessed with uncanny foresight, doomed to be disbelieved” — applies equally well to other figures Lewis has identified and raised from obscurity, from Paul DePodesta, the Athletics’ stats guru in Moneyball, to Michael Burry, the hedge-fund manager with Asperger syndrome who anticipated the subprime mortgage crisis in The Big Short.

The Premonition is not, however, a history of COVID. The pandemic does not even begin until halfway through the book. Donald Trump’s name barely appears and Anthony Fauci is mentioned only twice. Instead, Lewis tells a different story, showing how our decentralized health-care system proved inadequate to handle a global crisis while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which might have coordinated a national response, was not up to the task. Like many large bureaucracies, Lewis writes, the CDC had become ossified and risk-averse. It was adept at producing scholarly papers but reluctant to take action before it had perfect data. Such data is always hard to obtain and while the agency dithered, valuable weeks were lost. Dean, in fact, proposes, tongue-in-cheek, that the CDC should be renamed the Centers for Disease Observation and Reporting.

Lawrence recalls meeting Lewis for the first time when he was sent some early chapters of Liar’s Poker, Lewis’ first book, about his experience as a young bond trader at Salomon Brothers and, by extension, the evolution of an investment-banking culture that transformed the global economy.

“It took me about 20 seconds to realize this was really good,” Lawrence says. When Lewis expressed concern that he was going to have to turn from his rollicking first-person account to tell the back story of how the bond market came to be, Lawrence reassured him. “If the rest of the book is as good as the first two chapters, no one will care.”

Like many Princeton graduates before and since, Lewis had drifted to Wall Street for lack of a better idea of what to do with his life. Raised in a wealthy family in New Orleans (named Michael Monroe Lewis, he is related to the explorer Meriwether Lewis and President James Monroe), he majored in art history at Princeton and, in an oft-told story, was finishing a master’s degree at the London School of Economics in 1984 when he was invited, through a distant cousin, to what was advertised as a dinner party for the Queen Mother at St. James’s Palace. The “dinner party” turned out to be more of a fundraiser, but nevertheless he was seated next to the wife of a Salomon Brothers partner who persuaded her husband to give him a job. Without realizing it, she also had gotten him a front-row seat to the circus as the ’80s boom began.

Liar’s Poker appeared in 1989, a little over a year after the 28-year old Lewis walked away from a six-figure banking salary to write it, and was an instant hit, defining an era. Lewis spent much of the next decade as a magazine writer for The New Republic, Vanity Fair, The New York Times Magazine, and other publications. He further developed his knack for telling stories through quirky characters, such as Morry Taylor, the tire-company executive whose spectacularly unsuccessful bid for the 1996 Republican presidential nomination became a central part of Lewis’ campaign narrative, Trail Fever. Not long before his death, Tom Wolfe, to whom Lewis has sometimes been compared, called him “probably the best current writer in America.”

Lewis’ work has occasionally been criticized, as well. Sports journalist Allen Barra blasted Moneyball for misunderstanding baseball’s dynamics and misrepresenting its history. Responding to Lewis’ 2011 Vanity Fair article on Germany’s role in the world financial crisis (titled, “It’s the Economy, Dummkopf!”), The Economist asked, “Is Michael Lewis’ writing rolling downhill?”

According to the market, the answer seems to be: surely not. His books have continued to sell well and receive largely positive reviews.

On each side of the desk in Lewis’ home office sits a large manila folder. The one marked “Hot” holds material related to what he is currently working on. The one marked “Cold” contains scraps of information about subjects that interest him but have not gelled into a book proposal.

The story that eventually became The Premonition began in the Cold folder. Friends often push story ideas on him, and long before COVID began one friend had been particularly insistent that Lewis write about DeRisi, a former MacArthur fellow who had developed a way to rapidly identify viruses. Lewis met with DeRisi and was intrigued but decided that he lacked the scientific background to turn his story into a book. The idea lay idle for five years, but when the pandemic emerged, Lewis learned that DeRisi was turning his lab into the nation’s largest COVID testing center. “It’s going to be the biggest flashlight in California, and we’re going hunting for virus,” Lewis recalls DeRisi telling him. “And I thought, if I go along for that ride, I will be able to learn enough.” DeRisi introduced him to Dean, his research and interviews uncovered other interesting figures, and suddenly, the story moved from Cold to Hot.

For a source, talking to Michael Lewis is not a casual undertaking. He conducts multiple interviews in multiple sittings over many hours and does not record his interviews. “I find that when people have a tape recorder in front of them they are less likely to be their natural selves,” he reasons. “Also, if by chance someone I’m writing about finds themselves getting in a lot of trouble for something I have quoted them saying, I don’t want there to be a tape that’s going to condemn them.”

The act of taking notes is itself important, Lewis says. “I’m editing as I go, deciding what’s worthy of putting down on paper, so it triggers higher alertness of what’s going on. I can tell by the notes I have at the end of the day what just happened. I’ll go out with someone and think, oh that’s interesting, and come back with a page and a half of notes, and I’ll realize that’s telling you something — that you weren’t actually all that interested in what was going on. And other days I’ll come back and a big, thick notepad will be just destroyed, and I’ll go, there’s gold in these hills.”

Lewis says most people talk to him, not because they are familiar with his books, but because they have seen the movies that have been made of them. Charity Dean had never read any of his work, Lewis says, but agreed to the interviews because the fact that he is so prolific gave her confidence something would ultimately come of the project.

Occasionally, stories that make it to Lewis’ Hot folder fail to develop, but he says his dry holes tend to be shallow. One exception was a book called Underdogs, which was conceived as a sequel to Moneyball; the two books were, in fact, pitched to Norton as a single project. Lewis intended to spend the first book examining the baseball-analytics revolution before turning to the young prospects who were the products of that revolution — the kids who, as he puts it, “were drafted by an algorithm.” After six months, though, he realized that he had said everything he needed to say about both subjects in Moneyball. “The success of the first book,” he says now, “killed the second.”

In the midst of success and tragedy, Lewis still embraces optimism. A man who blithely assumed he wouldn’t catch COVID by hanging around with doctors (and as of late July had not caught it) is unlikely to fret that America will contract a terminal case of authoritarianism from its recent exposure to the alt-right. In that light, and the shortcomings of its health-care system and political leadership notwithstanding, it is unsurprising that Lewis views the country and its future with hope.

“It’s still an incredibly successful experiment,” he says of America in 2021. “But we’re drama queens. I don’t think we’re suicidal. People mistake what’s on cable news for the country. Cable news is not the country.”

To see the real country, he recommends, get out of your house — even during a pandemic, if need be. “The typical corporate conference is more like [America], the typical church gathering, the local Little League,” Lewis continues. “We’re a country that’s really rich in healthy institutions. When you push slightly below the surface politics of a given person, the people you think of as Trumpers or as lefties, if they’re in a room doing something together, they aren’t as different in their values as it may seem.”

“So,” he says, “I’m not all gloomy and doomy about what’s going on.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.