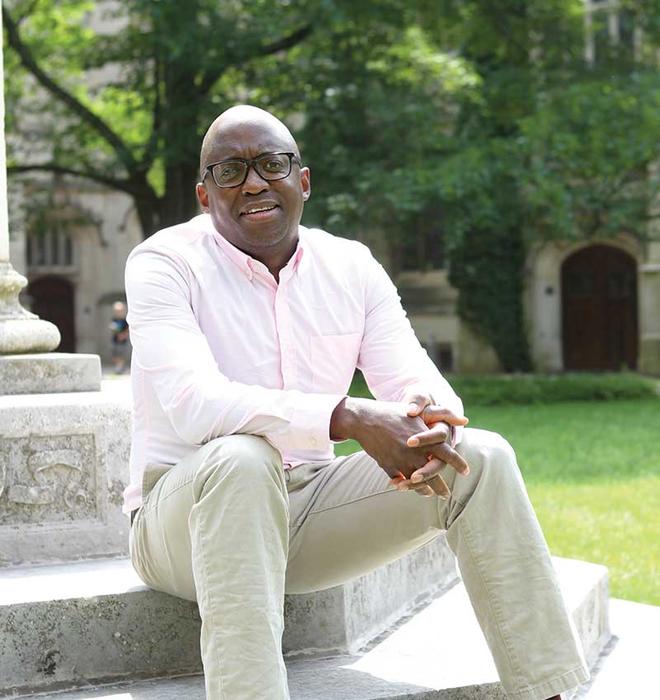

Historian Jacob Dlamini, born and raised in South Africa, seeks to tell nuanced stories about the apartheid era. His job is especially fraught.

Dlamini’s efforts are often dismissed by his countrymen: “‘Why are we even writing books about apartheid? We know what it was,’” is a common refrain, he says. Yet “the level of ignorance is astounding,” says Dlamini, a Princeton assistant professor of history since 2015. “People think, ‘We know enough, so there’s no need to be going back.’ And because of this ignorance about the past, people make these easy jumps and will reach easy conclusions.”

Within the last 10 years, Dlamini (pronounced la-mee-nie) has published four books on the country’s history, an output inspired not just by his own apartheid-era experiences, but by his view that South Africans are increasingly embracing revisionist histories. He believes this trend can be linked, in part, to citizens’ disillusionment with the post-apartheid government, which he says has veered sharply from a democracy into a fulsome kleptocracy over the last 10 years or so.

“We spent the past 25 years frittering away whatever moral authority we had for defeating apartheid,” he says. “And we’ve engaged in a grand corruption.”

Dlamini’s work refines the narrative around apartheid, often by exploring uncomfortable subjects. In Safari Nation, published in 2020, Dlamini dispels racial stereotypes around conservation and environmentalism by showing the long history Blacks have had in the operation of South Africa’s Kruger National Park. “There is this very ugly history of environmentalism and racism in South Africa where whites are the naturalists and the conservationists and Blacks are the poachers, the destroyers,” Dlamini says. “And so I come along to tell a much more complicated story.” Another book concerns former members of the African National Congress (ANC) who became informants for the South African Security Police. And Dlamini is working on a book that seeks to show how the apartheid state’s hunger for conformity endangered even its white soldiers. That book’s subject is a former military psychiatrist who exposed white South African troops to brutal and humiliating forms of treatment to “cure” them of homosexuality and other so-called vices.

Among the oversimplifications that have begun seeping into the nation’s revisionist history is one that goes like this: As older Black South Africans watch the country’s apartheid-era physical infrastructure crumble while public funds for repairs are subverted by graft, many reflect fondly upon the “efficiency” of apartheid leaders, who oversaw massive — and highly unequal — public-works projects.

“We know that [apartheid leaders] were not efficient,” Dlamini tells PAW via Zoom. “They had to create something like 13 education departments to serve different ethnic groups!” And then there was a bloated welfare system for white South Africans, including state-sponsored education; Blacks, on the other hand, had to pay for schooling that was “designed to be inferior” and meant to produce laborers, says Dlamini. The apartheid leaders “were brutal. You should never for a second mistake brutality for efficiency,” he says.

Some Black South Africans, fed up with skyrocketing crime, openly romanticize the “law and order” of the draconian apartheid Security Police, as Dlamini chronicles in his 2009 book, Native Nostalgia. “It is both illuminating and unsettling to hear ordinary South Africans cast their memories of the past in such a nostalgic frame,” he writes. “It is illuminating because it sheds light on ‘ordinary’ understandings of our past. It is also unsettling because it reveals that South Africans are not agreed on the meaning of their past.”

The country’s past set the stage for apartheid — the term means “separateness” in Afrikaans — with informal segregationist policies dating back to 17th-century Dutch colonizers. In 1948, South Africa, then a member of the British commonwealth, formally adopted the practice of apartheid after the political ascension of the National Party, which aimed to secure political, social, and economic power for the nation’s minority white Afrikaners.

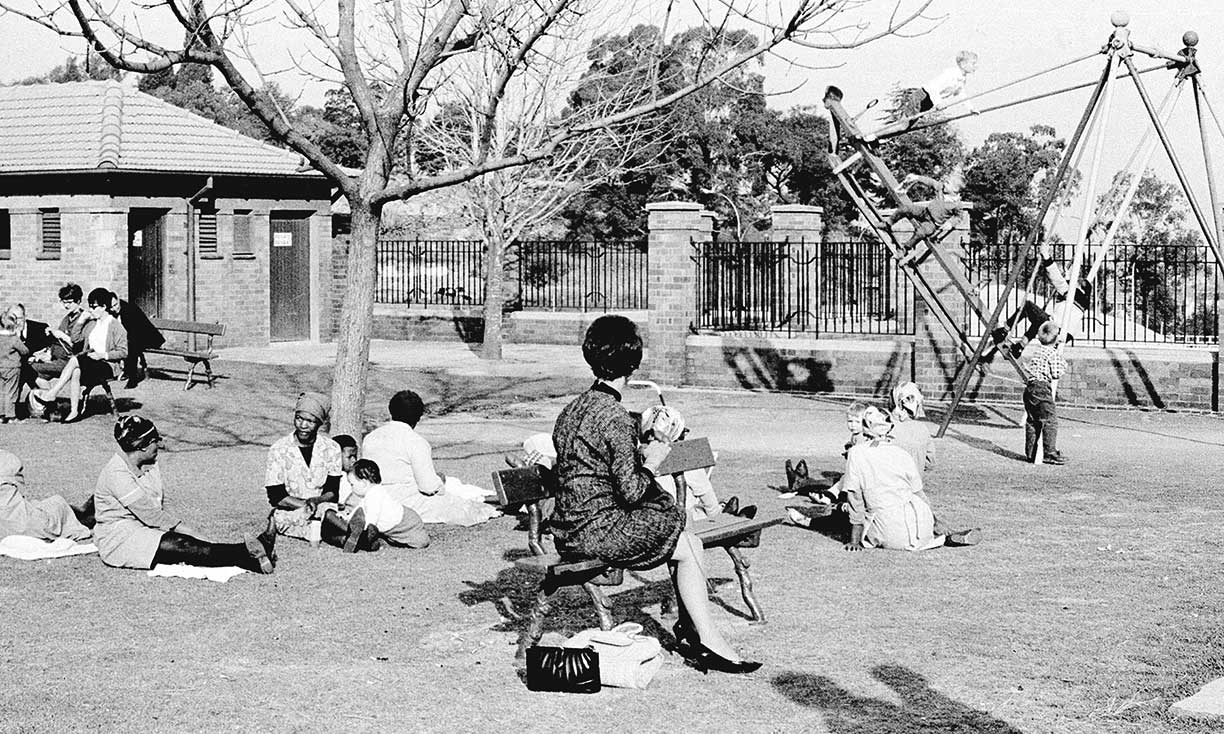

No aspect of life was untouched by apartheid. One of the first laws enacted under the system outlawed marriages between European whites and non-whites. Soon all interracial sex and marriage was criminalized. Then came the Population Registration Act of 1950, which classified South Africans into three racial groups: Native, European, and colored.

Between 1960 and 1983, the nation underwent one of modern history’s largest mass evictions as 3.5 million Black South Africans were forced out of their homes and into designated tribal homelands. In terms of land dispossession and systematic marginalization, says Dlamini, “Black South Africans’ experiences match much more directly, I think, to the Native American experience,” than to the Black American experience.

Still, Dlamini says, “not everything a Black person did in apartheid was in response to apartheid. Falling in love was not in response to apartheid, parents doing things with their kids, kids playing games — that was not overdetermined by apartheid. It’s not to ignore the circumstances of the conditions, but it is important to acknowledge that Black communities created networks of solidarity or what we might call moral capital, which helped me growing up in apartheid to know the difference between right and wrong.” He continues: “A big part of my commitment is to cut race down to size. To look for those instances where race doesn’t explain everything.”

Dlamini was born in 1973 and raised about 30 minutes outside of Johannesburg, in Katlehong, one of many so-called townships erected along the outskirts of metropolitan areas in the mid-20th century. By lining major cities with these townships, the apartheid government created an accessible source of labor for cities. Katlehong was a warren of nameless streets, with sometimes-unreliable public utilities, but it also had cinemas, swimming pools, and dance halls, all of which added up to “a vibrant township with a rich cultural and social life,” he says. “Apartheid tried to stifle that. It failed.”

Mostly meager, semi-detached homes with concrete slabs and asbestos roofs were adjoined by modest yards. Some families of means had large houses, while the poor let out sheds in their yards to those even worse off.

Dlamini was raised by his single mother, a well-respected figure in the community, who worked as a janitor at a local women’s hostel. Education was her highest priority for her only child, and she ensured that Dlamini was taught by the best teachers at his government schools. Television was banned until 1976, but for years afterward, sets remained scarce in his township. Anyway, Dlamini’s home lacked electricity for his first 11 years of life. So books and his transistor radio became portals to the outside world. The young Jacob followed sports and the news on Radio Zulu; he developed a taste for pop music — Billy Idol, Prince, U2 — but learned quickly not to grow attached to an artist, as the apartheid state blacklisted musical acts for the least whiff of subversion.

In Native Nostalgia, Dlamini grapples with his childhood. “What does it mean to say that black life under apartheid was not all gloom and doom and that there was a lot of which black South Africans could be, and indeed were, proud?” he writes, referring to how Black South Africans created and relied on social and familial networks that helped people through adversity emotionally or via pooled resources.

The Security Police cast menacing shadows over his childhood memories. At age 10, as he returned from an errand, a woman’s scream — louder than anything he had ever heard — sliced the afternoon air. Soon Dlamini was overcome by a noxious cloud of tear gas. Confused and half-blind, he could just make out the figures of adults on the street running for shelter or to nearby water sources to drench their T-shirts to use as protection against the gas. A police patrol had come by, he explains. “And to break the boredom, to amuse themselves, they would every now and again just fire tear gas to see how people would react.”

A few years later, Dlamini opened his front door to a group of police officers looking for an uncle rumored to be dealing diamonds. Home alone, Dlamini watched in horror as they marched in and demanded to speak with the uncle. He was not there, and though the police soon left, Dlamini still recalls his terror. “The last thing you wanted was to find yourself in the [Security Police’s] hands,” he says. “These were mean, evil people with all the power in the world. These were people who could do things to you, who could make you disappear.”

In his final year and a half of high school, four years before the end of apartheid, Dlamini’s mother died. “My mother died without having voted in her country of birth. She died without having become a citizen in the country of her birth,” he says. “I don’t celebrate any of that stuff, but I do celebrate her life, the advantages she gave me, and her insistence on the value of education.” Dlamini paired his inheritance with a scholarship to attend a progressive private boarding school, St. Barnabas College, in Johannesburg, which had opened in 1963 as one of the first racially integrated schools in the country. It was the first time Dlamini was taught by and alongside white people. His education there was formative. “I was introduced to more books than you could read, but also, I was introduced to teachers who were committed to helping us learn despite the odds,” he says, noting that many of his teachers had relatives who had been jailed for their anti-apartheid activism.

After graduation and a six-month apprenticeship in a program intended to train Black journalists, Dlamini became a reporter at The Sunday Times, Johannesburg’s biggest newspaper. He spent six years as a reporter, covering, at a safe distance, a national conflict that between 1987 and 1994 took 12,000 lives. “Very few South Africans are prepared to call this what it was: a civil war,” Dlamini says. “The genius in Mandela was in seeing this and helping to stop it.”

That episode in South African history is the focus of another book project. “In the mainstream media, [the civil war] was often referred to as an ethnic conflict between so-called Zulus and so-called Xhosas,” says Dlamini. But, he explains, the South African province where the violence began in the late 1980s was “Zulu-speaking people against Zulu-speaking people. So to call this an ethnic conflict just makes no sense.”

Dlamini’s experiences as a Black apartheid-era journalist are integral to his scholarship, according to history-department colleague Emmanuel Kreike. “Jacob comes from a system that was set up to spy on [its citizens], and he really wants to expose what lengths this system went to,” says Kreike, director of Princeton’s African studies program.

Kreike refers to Dlamini’s 2015 book, Askari: A Story of Collaboration and Betrayal in the Anti-Apartheid Struggle, which offers an empathetic account of apartheid spies called askaris, informants who are widely demonized in South Africa today. By using the story of one askari, a former member of the ANC, Dlamini shows how political activists frequently became police informants after prolonged harassment and physical and psychological torture. The book paints a morally ambiguous picture of these unlucky souls who defy categorization as “traitors” or “collaborators.”

“How does a hero of the ANC become a despicable spy for the apartheid state?” asks Kreike. “He’s still a human, but the process of that transformation is still important to understand who we are even now, today,” he says. “That’s one of the reasons why [Dlamini] gets criticism within South Africa. He’s not against the history of the heroes, but he says, ‘you know, the apartheid era was not only about the heroes.’ ”

Another book, The Terrorist Album: Apartheid’s Insurgents, Collaborators, and the Security Police (2020), sprang from Dlamini’s research for Askari. “Former members of the apartheid Security Police [would] refer to this thing called the “terrorist album,” he recalls. Dlamini’s book is the first to seriously examine this notorious photo album, which he calls “a perfect allegory of the nothingness that was apartheid.” The album is a sloppy curation of mugshots that were frequently ascribed to the wrong person, often due to bad information extracted through violent interrogation methods, and yet the Security Police relied upon that information to make life-and-death decisions in its pursuit of so-called terrorists of the state.

“It’s impossible to underestimate the importance of this work,” says Luise White, professor emerita of history at the University of Florida. “Instead of a history of an all-powerful racist state versus African victims, Dlamini shows us how frequently clueless the South African security apparatus was. That cluelessness made it more randomly violent, but it was rooted in an innocent trust of interrogated Africans.”

To be listed in the terrorist album might make you a potential askari. Dlamini traced the mugshot of an ANC insurgent named Odirile Maponya and discovered his father had been on the Security Police payroll as an informant for years, keeping apartheid authorities apprised of the movements of ANC members, including Odirile and another son, Japie. His information led to Japie being tortured by askaris in 1985 for information about his brother, Odirile, who was in exile. After failing to extract information, the Security Police realized Japie now knew the identities of askaris. To prevent him from revealing this information, they murdered him. Three years later, Odirile perished when an explosive device meant for white moviegoers detonated as he placed the bomb in a nearby garbage can.

When Dlamini presented living Maponya siblings with his evidence about their late father, they reacted with outrage, then denial. “Can the family celebrate Odirile without having, at the same time, to deal with questions about betrayal and collaboration at the heart of their family drama?” Dlamini writes.

He goes on: “How do we talk about the victims of apartheid violence without making it sound like every Black person was a victim of that violence? How do we talk about Black complicity with apartheid without making it sound like that complicity amounts to absolution for the crimes of apartheid? Do we need a new language to talk about the suffering caused by apartheid and by the complicity that made such suffering possible — a language that allows us to articulate both points without sinking into moral relativism?”

In reporting The Terrorist Album Dlamini found himself in once-unimaginable situations. He sat at the kitchen table of a high-ranking apartheid-era Security Police officer who, like other officers, had admitted to murdering dissenters, often members of the ANC. Dlamini felt apprehensive, and he reminded himself that this once-powerful authority was now a paunchy old man. (There has been little political appetite among the leaders of the democratic government to prosecute apartheid-era crimes, despite an ample record created by an ANC Truth and Reconciliation Commission.) The trepidation Dlamini felt in the officer’s kitchen wasn’t altogether misguided, as the septuagenarian veered from anodyne memories into racist screeds. But then, in an act once unthinkable, the officer made him lunch. The ironies, says Dlamini, were the most delicious part of the meal.

Today, Dlamini, who lives in Princeton with his wife and three daughters, describes himself as disillusioned by the endemic corruption in South Africa, but he insists that the positive changes made since apartheid fell cannot be marginalized. Most important, he says, people have a right to hold officials to account through their votes. Racial integration is the norm, and the Black middle class has greatly expanded. Still, in terms of education and economic performance, “On the whole, the people who have benefited the most from the end of apartheid have been white South Africans,” he says.

Dlamini feels a sense of urgency in his work to illuminate the country’s history: Aging Security agents are increasingly emboldened to speak about their actions, and many are beginning to share troves of archival material. Then there are the young South Africans whose desire to see the fall of various institutions and legacies have earned them the moniker of “the Fallist Generation.” Dlamini characterizes their engagement of the past as “superficial in ways that blind them.” Most troubling is their dismissal of Mandela, whom they see as a sellout more interested in appeasing whites than in seeking justice and fundamental transformation.

“Some of the choices made in the past were made because those were the only choices available,” Dlamini says. At a spring Zoom forum for history professors, he explained that he strives in his work to “keep sight of the individual, where you can point to an individual, and you can say, ‘You did this, you did that, and you need to be held accountable for that.’” He plans to continue to mine the archives of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, complicating the national narrative one story at a time.

Former PAW associate editor Carrie Compton is a senior communications specialist at the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies.

4 Responses

Stephen William Foster *77

4 Years AgoCapitalization Choices

The November issue contains a letter to the editor about the article about Professor Jacob Dlamini, published in September. The letter is from Bruce C. Johnson ’74 and raises the question about capitalizing “Black” but not capitalizing “white.” I have to say that I believe the issue to be important.

The Associated Press Stylebook is your reference for PAW’s reason for capitalizing black and not capitalizing white. Your handling of this issue is insufficient.

I believe that it could easily be argued, and I so argue, that the stylebook is racist in recommending that usage. You should have gone against the stylebook — that would have been to take the moral/ethical high ground. But you follow the recommendation of The Associated Press Stylebook without question. As an editorial decision, you should have gone against the stylebook, and use consistency for these references: Neither of the terms should be capitalized or both should be. Anything else is de facto racist, whatever the excuses.

I hope you will learn something from this issue and learn to do the right thing in this respect in the future.

Eve Thompson ’82

4 Years AgoParallels to the African American Experience

Thanks for sharing Jacob Dlamini’s take on the dynamics of South African history and how powerfully influenced it is by the point at which the country has arrived today (“Revising the Revisionists,” September issue). I am an African American who calls South Africa my home, having come here first as an anti-apartheid lawyer initially conducting a one-woman fact-finding mission on the political violence here that raged in the early 1990s. I found Dlamini’s take on the different aspects of collective memories of pivotal moments and issues during the apartheid era fascinating. I only disagree with his assessment that Black South African history can be better equated to Native American history than African American history. I don’t disagree that there are some parallels to the former’s history, but one shouldn’t be discouraged from searching for the parallels in African American history.

As someone who has moved between the two worlds, the similarity I find most striking is how much keeping our eyes on the prize of civil rights and liberation, respectively, prevented us from anticipating the downsides like the middle-class Black flight out of townships and ghettos further impoverishing the communities they left, economically and intellectually. That is where there is a distinct departure from Native American history. In fact, I would love Dlamini to undertake a comparative study of the impact of Black flight from poor areas in both countries. My observation is that the incredible level of civil society organization during the struggles in both countries is a shadow of its former self.

Bruce C. Johnson ’74

4 Years AgoBlack and white

Editor’s note: On matters of capitalization, PAW follows The Associated Press Stylebook, which uses the capitalized term “Black” because “the term reflects a shared identity and culture rather than a skin color alone.” The stylebook directs that “white” should be in lowercase.

Michael L. Sena ’69 *72

3 Years AgoOn Style and Politics

Referring to your response to a question from Bruce Johnson ’74 in the November 2021 issue of PAW, in which you say you are only following the orders of The Associated Press Stylebook when you capitalize “black” when it refers to a certain group of people and do not capitalize “white” when it refers to another group of people, it is clear to any reasonable person that the Associated Press has adopted a style for political purposes, not because it is consistent with a logical and consistent use of the English language. If the term “white” does not refer to a group with any similar characteristics other than skin color, then it is simply wrong to use it. If the term “black” can be used to group all people in the world who have a variation of the skin color black, then using the term certainly does the individuals an injustice. PAW, by blindly following this approach, is doing a serious injustice to both groups.

Editor’s note: For additional discussion of this topic, please see Marilyn H. Marks *86’s letter from the editor and Professor Carolyn Rouse’s essay, “Capital Crimes,” in the December 2021 issue.