In the 1970s, Toni Morrison led a hectic life. She was a promising novelist who held a demanding job as an editor at Random House. After a divorce, she was raising two young sons on her own. And like many working women, her commute — to her office in midtown Manhattan — was one of the few stretches of time she had to herself.

A new Princeton University Library exhibition offers a revealing look into how she juggled it all while producing powerful and award-winning work. The exhibition features never-before-seen pages from her day planners, the now-obsolete paper calendars that many of us once carried. In the pages of this most revelatory artifact of her life, Morrison’s days are filled with meetings with the authors whose work she edited — among them Muhammad Ali and Angela Davis — as well as more mundane appointments. But it is in the calendars’ margins where the most spectacular surprises lie. Several of the day planners carry phrases and sentences, with those from the mid-1970s holding the only existing drafts for one of her most important novels, Song of Solomon. Up until 2021, it was thought that all drafts for the novel had been lost in a 1993 fire at her home.

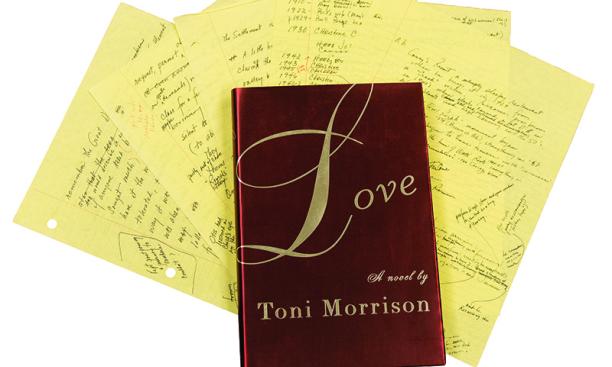

About 100 original archival items offer a view into “unexplored corners of her writing process and unknown aspects of her creative investments that only live in this archive,” says Autumn Womack, an associate professor of African American Studies and English who served as curator for the exhibit, which is at the Milberg Gallery in Firestone Library. Among the most tantalizing elements are hand-edited drafts of alternate endings for Beloved, her most famous novel and the winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction; unfinished projects, such as an outline for a play that was never performed; and hand-drawn maps that Morrison made to help her plot the geographical dimensions of her fictional worlds.

“Toni Morrison: Sites of Memory” is the first major exhibition dedicated to material from the Toni Morrison Papers. Morrison, who was the Robert Goheen Professor in the Humanities for 17 years at Princeton, worked with the Princeton University Library to preserve materials damaged in the fire. The collection, which the University formally acquired in 2014, includes approximately 200 linear feet of research materials, manuscript drafts, correspondence, editorial notes, diaries, photographs, speeches, dramatic works, and screenplays that provide insights into the creative process of the author, winner of the 1993 Nobel Prize in Literature, who died in 2019 at the age of 88.

The exhibition, open until June 4, covers many facets of Morrison’s life. There are letters from well-known authors such as Toni Cade Bambara. And there are photographs, outlines, drafts of speeches, and more, revealing much about her day-to-day life, her writing, and her friendships.

The University will celebrate Morrison throughout the spring with numerous arts and academic events. And 2023 will be a year of national recognition for Morrison with a commemorative stamp issued by the U.S. Postal Service.

A section of the exhibition titled “Beginnings” features a photo of Morrison as an undergraduate at Howard University on stage in a 1953 production of Richard III. Nearby is the opening page of an early short story titled Gia. The byline is Chloe Morrison, which was her given first name. A yearbook is open to a photo of Morrison, who was the associate editor of the Hi-Standard, the newspaper at her high school in Lorain, Ohio.

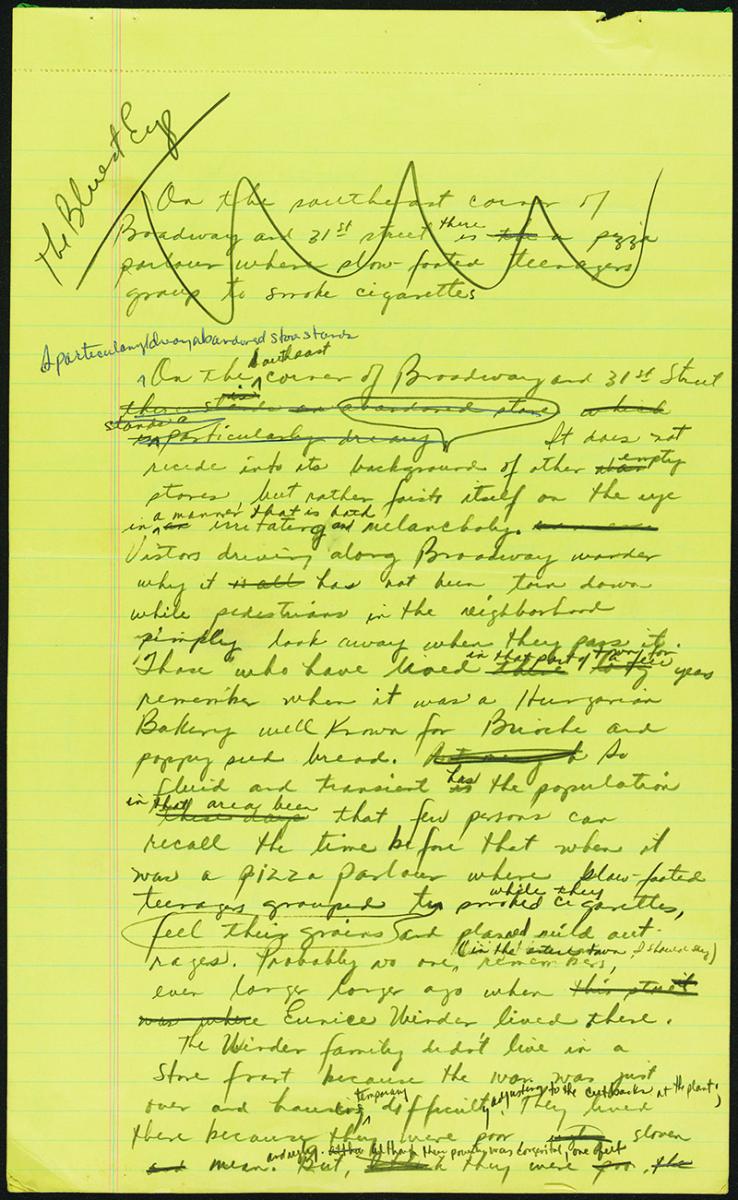

Letters and manuscript drafts in the exhibit provide insight into Morrison’s journey from editor to published author with the publication of her first novel. The Bluest Eye, about an African American girl who wants blue eyes like Shirley Temple, was published in 1970, when she was 39. There are several letters Morrison wrote asking editors for feedback on the manuscript.

In a March 1966 letter from Morrison to an editor at Macmillan seeking editorial advice, she describes the plot as “what happens when the Thing we long for — the Big Secret Miracle that, if it happens, will make everything all right — does happen.” The pages of the letter — and many other documents in the exhibition — are singed from the fire at her home. In the last paragraph, she writes, “it will be a mark of kindness if you read it, and I am, of course, very anxious about your reaction.” Another letter to Morrison, this one from an editor at Doubleday, suggests that she keep working on The Bluest Eye as a short story rather than a novel. It was advice she wisely ignored.

But she told no one at Random House that she was working on a novel. Her colleagues learned about it when they read the review in The New York Times.

Morrison kept an astonishing breadth of research material for her novels, Womack says. There are popular photographs, advertisements, newspaper clippings, historical maps, and music that helped her conjure the imaginative worlds she created for her characters. “In many interviews, she talks about how much research goes into a clause or a sentence, sometimes boxes and boxes,” Womack says. “This gives a sense and weight to that really meticulous research process, that curiosity, as she searched for the right mood, tenor, or word.”

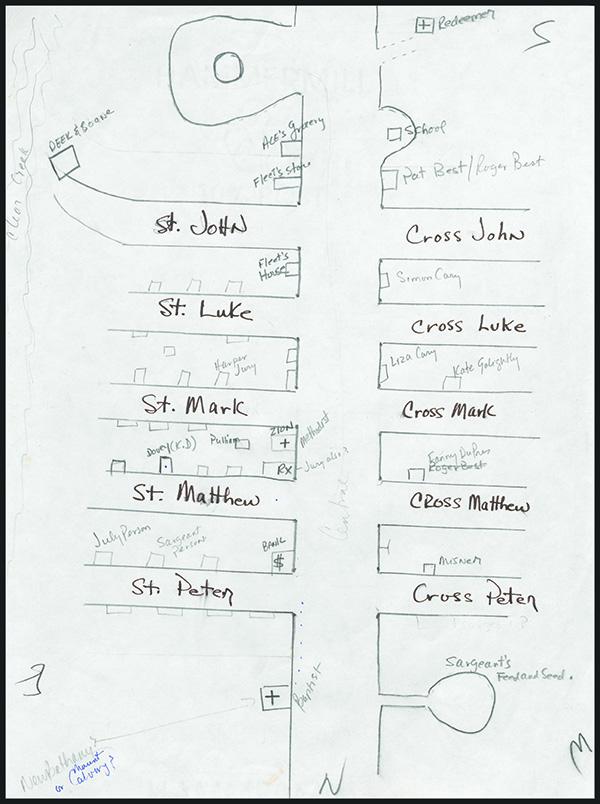

Her painstaking work is evident in the hand-drawn maps she made to render her fictional landscapes. The exhibition includes blueprints sketched by Morrison for the convent in her 1998 novel Paradise that are so detailed they include characters’ sight lines and notes about where and how the novel’s first moments occur, and drafted floor plans of the house at 124 Bluestone Road in Beloved. They demonstrate her careful attention to geography and topography in her work. “She is visualizing the house, how it is laid out, how the characters move through space,” says Jennifer Garcon, Princeton’s librarian for modern and contemporary special collections, who worked on the exhibition. Morrison labels items in the drawings the “cold room,” the “stone room” and “bedrooms,” and draws an arrow to the “restaurant.”

For Paradise, Morrison wrote to a friend who was traveling through Oklahoma and asked him to take photos of the landscape. Her handwritten notes are affixed to some of the photos, demonstrating the way she attached plot points and dialogue to specific images.

Also on view are lengthy excerpts from rarely seen footage of an eight-hour interview that Morrison gave over two days in 1987 as part of a project at Boston University. She talked about her early life and her writing methods, as well as her motivation for writing The Bluest Eye and the rejection letters she received for that work.

Her day planners are filled with notations of meetings with the writers whose work she was editing. Her nearly two-decade career at Random House began in 1965 at a subsidiary that produced textbooks. She later moved to editing novels and nonfiction as the first Black woman editor in the company’s trade division. The day planners are from “the heart of her editorial career at Random House,” Womack says. “We see her noting meetings with Davis, one of her writers, and notes on editorial feedback to give to Gayl Jones on her novel. We see her working on Ali’s biography. The notes in the margins are things she might say to him in an editorial meeting.”

Morrison’s busy schedule compelled her to use the early morning hours for work on her novels, as she explained in a 1993 interview with the Paris Review: “Writing before dawn began as a necessity — I had small children when I first began to write and I needed to use the time before they said ‘Mama’ — and that was always around 5 in the morning.” The habit of writing at dawn stayed with her: “I always get up and make a cup of coffee while it is still dark — it must be dark — and then I drink the coffee and watch the light come,” she said. “And I realized that for me, this ritual comprises my preparation to enter a space that I can only call nonsecular.”

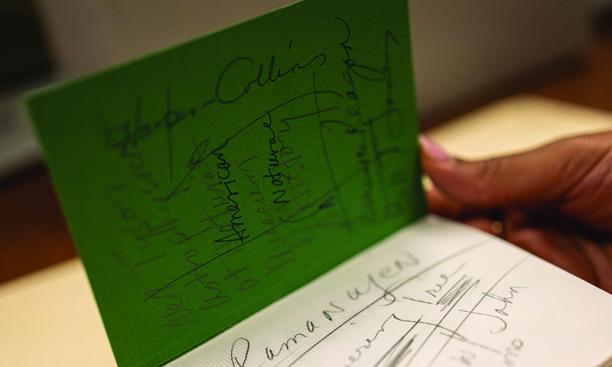

In the margins of the day planners from the mid-1970s, the curators discovered drafts of dialogue, outlines, and notes on characters for Song of Solomon, her 1977 novel, which was awarded the National Book Critics Circle Award. “There is prose that makes its way directly into the novel,” Womack says. “As she was having editorial meetings, she was writing on the side.”

“In many interviews, she talks about how much research goes into a clause or a sentence, sometimes boxes and boxes. This gives a sense and weight to that really meticulous research process, that curiosity, as she searched for the right mood, tenor, or word.”

Autumn Womack, assistant professor and curator of Morrison exhibit

Morrison described using her subway commute to work on her fiction in an interview in Salon in 1998: “I would solve a lot of literary problems just thinking about a character in that packed train,” she said. “And then sometimes I’d really get something good. By the time I’d arrived at work, I would jot it down so I wouldn’t forget.”

Some of Morrison’s drafts were lost in the 1993 fire. No complete draft of Song of Solomon has been found — the day planner jottings are the only known early versions of parts of the book. “This is the only place where a surviving draft that we know of exists,” Womack says.

Morrison mused on her habit of composing on whatever paper was handy in the Paris Review interview: “Sometimes something that I was having some trouble with falls into place, a word sequence, say, so I’ve written on scraps of paper, in hotels on hotel stationery, in automobiles. If it arrives, you know. If you know it really has come, then you have to put it down.”

Though she did extensive research for many of her novels, what fueled Morrison’s work was her imagination. When writing Beloved, she read just a handful of accounts of the life of the woman who inspired the novel, Margaret Garner, an enslaved mother who killed her child to spare her the same fate.

Garner’s story “was much more awful than it’s rendered in the novel, but if I had known all there was to know about her, I never would have written it,” Morrison recalled in the 1993 interview. “It would have been finished; there would have been no place in there for me. It would be like a recipe already cooked … . What I really love is the process of invention. To have characters move from the curl all the way to a full-fledged person, that’s interesting.”

To visit the exhibition online, go to http://library.princeton.edu/tonimorrisonexhibition.

Jennifer Altmann is a freelance writer.

Arts Events Pay Tribute to Toni Morrison

To coincide with the Princeton University Library’s exhibition on Toni Morrison, the University will hold a series of events celebrating the author, with art exhibits and performances at various venues as well as academic events, including a three-day symposium on Morrison’s work.

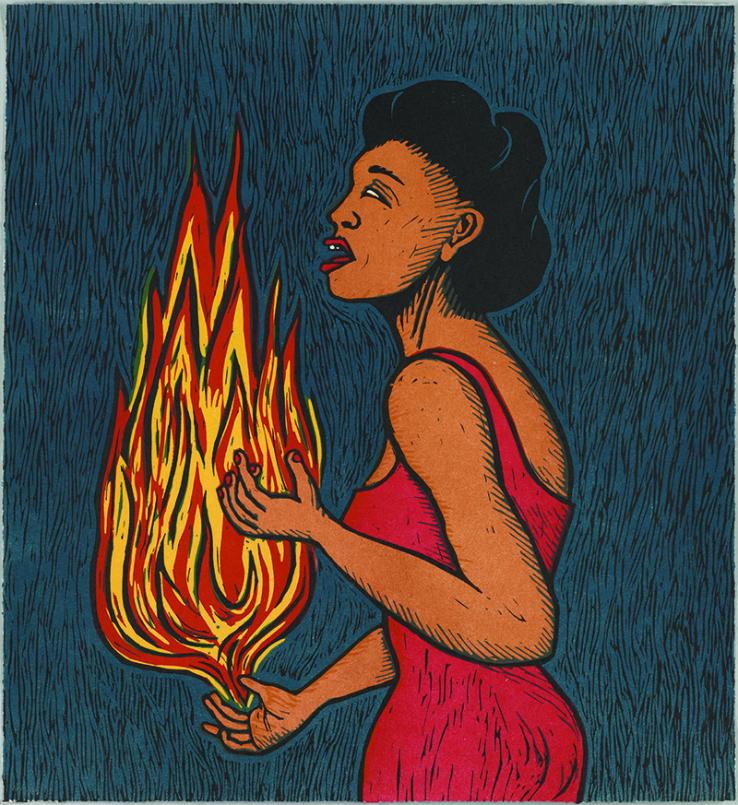

Artistic events include the exhibition “Cycle of Creativity: Alison Saar and the Toni Morrison Papers” at the Princeton University Art Museum’s Art@Bainbridge, the gallery on Nassau Street, through July 9. The exhibition brings together selections from the Toni Morrison Papers with sculptures, prints, and textiles by artist Saar, whose work weaves personal narratives with histories of the African diaspora that draw upon Black vernacular art, music, and spiritual traditions.

“By placing selections from Morrison’s papers alongside Saar’s potent artworks in various media, we will have the rare opportunity to see the overlaps between two brilliant minds at work,” says museum director James Steward.

McCarter Theatre commissioned performance artists Daniel Alexander Jones and Mame Diarra (Samantha) Speis to create original works reflecting the influence of Morrison’s work beyond the field of literature, to be performed March 24 and 25. The artists spent time exploring Morrison’s archive at the library. Of that experience, Jones says, “I was transfixed by snapshots of Ms. Morrison with a range of figures that suggest something about the ways she and other Black artists tended to one another over time and in quotidian motion.”

Princeton University Concerts will present a newly commissioned work inspired by Morrison’s archive, created and performed by MacArthur Fellow and three-time Grammy Award-winning jazz vocalist Cécile McLorin Salvant, on April 12.

The three-day symposium in March, “Sites of Memory: Practice, Performance, Perception,” will examine the multidisciplinary and collaborative nature of Morrison’s work as well as her writing practices, her unpublished writings, and her daily life as a teacher at Princeton, among other topics. The keynote speaker is author Edwidge Danticat. In the spring, the Department of African American Studies will present the Morrison Lectures, with scholar Farah Jasmine Griffin offering new interpretations of Morrison’s work.

Cotsen Children’s Library will exhibit “They’ve Got Game: The Children’s Books of Toni & Slade Morrison.” Open through June 4, the exhibit centers on the children’s book series Who’s Got Game?, which re-imagines Aesop’s fables and was written by Morrison and her son Slade.

A fall exhibition at the library, “In the Company of Good Books: Shakespeare to Morrison,” will feature objects from the library’s collections of English literature through four centuries, including Shakespeare’s first folio and previously unseen work by Morrison.