The Civil War was a catastrophe for the American nation, and it was only a little less of a disaster for Princeton.

On the eve of the war, there were 122 colleges and universities in the United States, with Yale being the largest with 447 students and 24 faculty. Princeton came in sixth (just behind the relatively new University of Michigan) with 273 students and 18 faculty. Surprisingly, four years of civil war did little to depress the prosperity of Northern colleges. But Princeton was the big exception.

The onset of the war created a crisis for Princeton: denounce Southern secession and risk the withdrawal of Southern students, or try to play neutral and become a pariah across the North. Neither strategy worked.

While other Northern colleges grew, Princeton’s student population fell, to 264, putting New Jersey’s premier college into the same decline as Southern schools that had literally been in the path of the conflict. By the second year of the war, Princeton’s treasurer admitted that “it became apparent” that with “the loss of the Southern students in consequence of the rebellion … the College could not get on with the means then at command.” At Princeton, only the number of books in its library grew, from 21,000 to 24,000. Whether the rest of it would survive was another question entirely.

The principal reason for Princeton’s downturn was its reputation as one of the safest Northern schools to which Southern parents could send their sons — safest, meaning unlikely to put disturbing notions about abolishing slavery into their heads. A “pro-slavery spirit ... impregnated the place before the war,” complained one 19th-century observer. Or if not quite an overt pro-slavery spirit, certainly a reluctance to endorse campaigns for social reform and anything that looked to upset the prevailing national compromises on slavery.

“It has not been the destiny of Princeton College to prove a nursery for the ultraists, the agitators and the fanatics of the day,” insisted one Commencement speaker in 1859. Indeed it wasn’t. Even though New Jersey adopted an emancipation plan for its slaves in 1804, the plan was laid out in a gradual timetable, and for some enslaved people in Princeton, a very gradual one. In the 1830 census, Princeton still listed 21 African Americans held legally in bondage. One Princeton faculty member, the mathematician Albert Dod, appears as late as the 1840 census, owning a teenage female slave. In 1843, a fugitive slave known locally as James Collins Johnson (and working at the College as a janitor) was recognized by a Southern Princetonian as a runaway from Maryland and arrested. Johnson would have been sent back to slavery but for an offer from a local Princetonian, Theodosia Prevost, to buy Johnson’s freedom from his owner.

On the eve of the Civil War, all six of the College’s alumni who sat in the U.S. Senate — John Breckinridge *1839 (the vice president), Alfred Iverson 1820 of Georgia, James Chesnut 1835 of South Carolina, James Alfred Pearce 1822 of Maryland, James A. Bayard Jr. 1820 of Delaware, and John Renshaw Thomson 1817 of New Jersey — were either Southerners, slaveholders, or pro-slavery Northern “doughfaces.” Whig and Clio halls both elected the future president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, as an honorary member in 1847 and 1849, and Whig Hall had Southern student majorities in its membership through almost the entire six decades leading up to the Civil War.

No surprise, then, that the debates on slavery that were sponsored by Whig Hall in 1802, 1817, 1819, 1839, and 1847 routinely resulted in condemnations of schemes to abolish slavery.

In 1859, after the failure of John Brown’s abolitionist raid on Harpers Ferry, Southern students paraded through Princeton’s streets “bearing such banners as ‘John Brown the horse thief, murderer and martyr.’” Effigies of Brown and Henry Ward Beecher, the most prominent clergyman in America and an outspoken New York abolitionist, “were consigned to the flames amid groaning and shouts.” This “demonstration of Southern sentiment and practices,” warned an incensed anti-slavery newspaper, showed the quality of Princetonians’ “bringing-up and rowdy proclivities,” and proved that “Princeton should be purged.”

And yet, Southerners and slavery did not have matters entirely their own way in Princeton. In 1847, Elias Ellmaker 1801, a lawyer from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, published a vehement assault on slavery in his The Revelation of Right, declaring an “eternal veto against all usurpation by man, and all tyranny, slavery, rapine and murder, in the name or under the titled authority of government.”

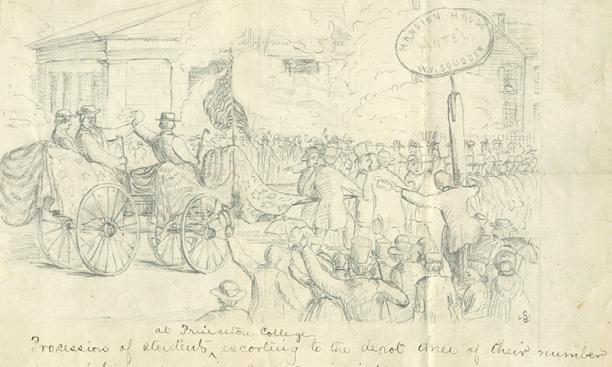

By 1858, it was possible for Elihu Burritt, a popular abolition lecturer, to draw “quite a large audience” in Princeton to promote the “gradual abolition of slavery by compensation to the owners.” When the newly elected anti-slavery president, Abraham Lincoln, passed through Princeton en route to his inauguration in February 1861, “the college students” at Princeton “were out in force; they gave the train a volley of cheers, to which Mr. Lincoln responded by bowing from the hinder platform” and “said a few words to the masses.” As the Southern states began forming a breakaway pro-slavery republic, Southern students began withdrawing from Princeton, and the New-York Tribune could report that “Princeton College has lost all its Southern students but about two.” In April 1861, when the new Southern Confederacy launched an attack on the U.S. garrison at Fort Sumter, in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, Unionist students “raised ... the Stars and Stripes on the cupola of old Nassau Hall.”

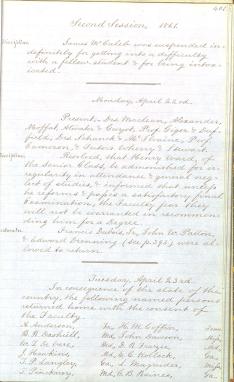

By the end of April, with Southern students gone from Princeton, the remainers formed “a volunteer corps ... under the name of the ‘Old Nassau Cadets.’” In June, at Commencement, The New York Times happily noticed “the thundering applause with which the students honored every expression of devotion to our Government and Union, and of abhorrence of secession and rebellion.” On Sept. 13, “a party of overzealous Union students” ambushed two classmates, Francis Dubois 1863 and Alexander Fullerton 1864, “who expressed secession sentiments,” and subjected Dubois to a ducking under the College pump “to put out the secession fire in him.” The faculty, under President John Maclean Jr., promptly punished three of the duckers with suspension, but not without explaining that the faculty’s disapproval should not be mistaken for a lack of sympathy with “those who are engaged in efforts to maintain the integrity of the National Government.”

By March of 1863, the student-run Nassau Literary Review was finally willing to embrace emancipation as a goal of the war. “Inestimably better is it that freedom should die honorable than draw out a miserable existence under the crushing heel of slavery,” wrote one student contributor. The only acceptable conclusion to the conflict would be “to secure to coming generations that great desideratum of all nations as well as individuals — Human Liberty.”

But there was a price to be paid by Princeton College for this. “Naturally,” reported the local Monmouth Democrat in May 1861, “the revenues of the institution, which has been so largely in favor throughout the South will be materially diminished.” As they surely were. By November 1863, the student body had shrunk by 20%, to 223. Yale, meanwhile, had grown to 457.

There are 62 names on the panel in the Memorial Atrium devoted to Princeton’s Civil War dead, although the most recent archival review has revised the number of casualties to 86. Of those, 47 enlisted in the Confederate armies and fought for the South; 39 fought for the Union.

That does not, however, account for the number of Princetonians who served in the war, which tops more than 600. When we consider that, in 1861, Princeton’s living alumni probably amounted to around 3,600, this means that 17% of Princetonians wore some kind of uniform between 1861 and 1865.

That also does not reckon with the number of Princetonians who served the Union or Confederate governments in civilian capacities. William English Lupton 1863, for instance, appears on the panel as a casualty of the war. In strict fact, he served with the Freedman’s Relief Association, and died in Nashville, “seized with a fever,” in 1864. Both of New Jersey’s Union governors, Charles Olden and Joel Parker 1839, were Princetonians of a sort. Olden never attended the College but had been the College’s treasurer from 1845 to 1869. Parker was a rabid anti-war Democrat and spent most of his governorship attacking Lincoln and emancipation.

The most prominent Princetonian on either side was Breckinridge, who had the inestimable Princeton credential of being the great-grandson of John Witherspoon and the son of a Princeton alumnus. He was also only a “resident graduate” student at Princeton for six months in the winter of 1838-39, but that did not prevent him from joining Whig Hall. Breckinridge was Kentucky-born and was elected as James Buchanan’s vice president in 1856. He was the presidential candidate of the deep South splinter faction of the Democratic Party in 1860, and once the Civil War began, defected to the Confederacy, where he served as a major general in the army and as Davis’ last, desperate secretary of war in 1865.

Breckinridge, though, stands only a little higher than the Princetonian who lost the vice presidency in 1856, William Lewis Dayton 1825. Born in nearby Basking Ridge, Dayton practiced law in Freehold, New Jersey. He was named to the state supreme court in 1838 and served in the U.S. Senate. Like Lincoln, he began political life as an anti-slavery devotee of the Whig Party. One contemporary put him on the same pedestal as another famous Whig, Daniel Webster: “His form, his manner, his voice, his diction, in fact his whole personal presence, was magnetic, and … I may say godlike.”

In 1856, when the Whig Party collapsed and a new anti-slavery Republican Party was formed in its place, Dayton was named as the party’s first vice-presidential candidate. Dayton’s Republicans lost that election, but not the one in 1860 that elected Lincoln. Two weeks after his inauguration, Lincoln named Dayton as the United States diplomatic envoy to France, and by May, Dayton was in Paris. Until his death from a stroke in November 1864, Dayton labored to keep the French emperor, Napoleon III, from meddling in the Civil War on behalf of the Confederacy and to discourage French investors from lending money to the Confederate government or building warships for its navy.

The nearest in prominence or rank to Dayton among Union Princetonians was Francis Preston Blair Jr. 1841. As the son of a fabled Washington political manager, Francis Preston Blair Sr., Blair was also a protégé of another famous string-puller, Thomas Hart Benton, and followed Benton into opposition to slavery. He joined the new Republican Party, sat in the 36th and 37th Congresses, and finished the war as a major-general and commander of the 27th Corps on William Sherman’s “March to the Sea.” By Sherman’s estimate, Blair was “one of the truest patriots, most honest and honorable men, and one of the most courageous soldiers this country ever produced.” Blair was also a deeply dyed racist who believed that Black people were “a semi-barbarous race” whose next step after emancipation had to be expulsion from the United States.

At least Breckinridge and Blair survived the war. The same, of course, cannot be said of Dayton or the 62 individuals who appear on the Memorial Atrium panel. Of these, however, only two can be said to stand out from the dark backdrop of the Civil War in any noticeable way, those two being Lawrence O’Bryan Branch 1838 and James J. Archer 1835, both of them Confederate generals. The first was killed at the battle of Antietam, and the second was captured at the battle of Gettysburg. Branch, as Confederate historian Robert Krick drily observed, was lacking in “any native dignity or honesty.” Archer was “noncommunicative,” “rough and unattractive,” and died in 1864 after imprisonment wrecked his health.

Curiously, at least three sets of brothers are represented on the Memorial Atrium panel. The Virginians Peyton Randolph Harrison 1851 (who is misdated as Class of 1831) and his brother Dabney Carr Harrison 1848 fought for the Confederacy, and died, Peyton at First Bull Run in 1861, Dabney at Fort Donelson in 1862. Thomas Falconer 1856 and William Bracey Falconer 1856 both joined Clio Hall, managed a plantation in Mississippi, served as Confederate officers, and died of illnesses in 1861 and 1863.

Two Unionist Hunts are listed on the panel, one of whom — Gavin Drummond Hunt 1863 — died of wounds received in the great assault on Missionary Ridge in 1863. The war also touched one faculty family. Charles Hodge Dod 1862, whose father was the last Princeton faculty slaveowner, served as a captain in the 2nd New Jersey Cavalry until his death from fever in 1864.

The panel does not mention a Princeton alumnus who was the most famous casualty of the war, Abraham Lincoln — even though, of course, his Princeton degree was an honorary one. “I have the honour to inform you,” President Maclean wrote to President Lincoln on Dec. 20, 1864, “that, at the semi-annual meeting of the Trustees of this College this day, the Degree of Doctor of Laws was conferred upon you, by the unanimous consent of the Board.” Lincoln replied a week later, accepting the honor with his customary grace. “The assurance conveyed by this high compliment, that the course of the government which I represent has received the approval of a body of gentlemen of such character and intelligence in this time of public trial, is most grateful to me,” Lincoln wrote. He then added, almost as if with an eye cocked on Princeton’s pre-war reputation, “Thoughtful men must feel that the fate of civilization upon this continent is involved in the issue of our contest. Among the most gratifying proofs of this conviction is the hearty devotion everywhere exhibited by our schools and colleges to the national cause.” Lincoln’s letter is today one of the treasures in the Firestone Library’s Special Collections.

It may give a somewhat different view of Civil War Princeton if we turn from the panel to look at the fate of a single class of Princetonians, the Class of 1863, who entered Princeton in 1859 and were caught squarely in the middle of their college careers by the war. Of the 111 who attached themselves, however briefly, to the Class of 1863, 62 took no part in the Civil War. Eighteen left for the Confederacy and never returned to take a degree; 22 served in the Union forces (20 in the state volunteer services, two in the U.S. Navy). In other words, an impressive 37% of this class donned uniforms for the war. (Of these, six on each side died.)

Others performed slightly different, and safer, service. One passed the war in the New York state militia, while two served as civilians in the U.S. Christian Commission, and one (Lupton) with the Freedmans’ Relief Association. Generally, the Union members of 1863 received their degrees in absentia, as if to say that their service was sufficient to make up for two years of doing something very different than study. There was one exception: Henry Seymour Holden 1863, who showed up for Commencement in 1863 “in his army blue.” (Holden did not enjoy his degree for long, dying just five months later).

The Civil War “gave Princeton a blow under which she reeled, and from which she was long in recovering,” remembered William M. Sloane (who was a Princeton faculty member from 1877 to 1896), “her resources were crippled, her interests divided” and the entire institution faced “utter shipwreck in that dark hour.” It required the advent of a new president, James McCosh, in 1868, and a new post-Civil War generation of academic professionals in the faculty to restore the College.

That would include wooing back the Southern constituency. In 1865, Princeton’s first instinct was to celebrate the return only of its Union veterans, and, as one Southern veteran of the Class of 1849 complained, “the authorities thought it necessary to emphasize their loyalty to the union in a way that exasperated all ardent Southerners like myself.” This “bitter feeling lasted for some years after the war.”

But old habits died hard. Whig Hall attempted to elect Robert E. Lee as an honorary member in 1869 and 1870. It failed, but by the 1890s, Princeton was yielding to the spirit of reconciliation that was sweeping so much of the country.

In 1915, Yale dedicated a memorial that listed its Confederate and Union dead together, and by the time the Princeton Memorial Atrium was created in 1920, University president John Grier Hibben 1882 insisted that the names of Princeton’s Civil War dead should likewise be inscribed on a panel without any indication of their allegiance in the war. “The names shall be placed alphabetically and no one shall know on which side these young men fought, save as an old family name is recognized by the passerby, as from Massachusetts, or Pennsylvania, or New Jersey.”

It was a generous sentiment. Whether it was a wise or true one is another question, and one with which Princeton still struggles.

Allen C. Guelzo is the Thomas W. Smith Distinguished Research Scholar in the James Madison Program at Princeton. He has written on Civil War history for The New York Times, The Atlantic, the Journal of American History, and has been featured in numerous television documentaries on Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant. He is the author of Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War and Reconstruction (2012) and is a three-time winner of the Lincoln Prize, for Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President (1999), Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America (2004), and Gettysburg: The Last Invasion (2013), which was also a New York Times bestseller.