When the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the use of race in admissions as unconstitutional in June, rising sophomores Zavier Foster and Zach Gardner had very different reactions.

Writing “with a heavy heart” on behalf of the Princeton Black Men’s Association, Foster expressed dismay at the thought of “how many underprivileged Black and Brown students will be unable to gain access to elite institutions due to these backwards rulings. … We already mourn the opportunities that have been ripped from minorities across the country.”

Gardner, in an opinion column for The Princeton Tory, waxed ecstatic and caustic about President Christopher Eisgruber ’83’s calling the decision “unwelcome” and “regrettable.”

“The Constitution had a great week at the Supreme Court,” wrote Gardner, an aspiring lawyer and member of Princeton’s Federalist Society. He voiced hope “that students from all walks of life can be assured that they will be evaluated … as unique individuals who will make valuable contributions to their campus, their community, and their country.”

Even now, tens of thousands of high school seniors around the country and the world are taking SATs — optional since the pandemic — and polishing essays in hopes of walking the campus pathways with Foster and Gardner. Princeton in August tweaked the short essay questions on its application to comply with the Supreme Court ruling, including asking applicants to write about how “your lived experience has shaped you.”

That is a nod to the allowance Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. offered in the majority opinion overturning the outright use of race in admission decisions at his alma mater, Harvard, and the University of North Carolina, “[N]othing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise.” But Roberts added this caveat: “[U]niversities may not simply establish through application essays or other means the regime we hold unlawful today.”

Princeton will now try to figure out how to thread that needle. In August, the Board of Trustees established an ad hoc committee to examine Princeton’s admission policies, guided by two key principles: merit-driven admissions and the imperative to attract students from all sectors of society, including underrepresented groups. It presumably will review whether to keep the boost that children of alumni get in admissions. The Class of 2027 included 13% of students who are legacies, according to the University.

Eisgruber, a constitutional scholar, declined an interview request, as did Dean of Admission Karen Richardson ’93.

PAW spoke with the Princeton-educated presidents of Northwestern University, Hamilton College, and Willamette University who are wrestling with the same dilemma of how to achieve diverse student bodies with a principal tool off the table. We also sought the views of expert faculty and alumni.

The fear among educators is that what happened at UCLA, Berkeley, and other University of California campuses after voters passed Proposition 209 in 1996, and again in Michigan when voters there banned affirmative action in 2006, will repeat itself. Enrollment of Black students plunged by more than half but subsequently has largely rebounded.

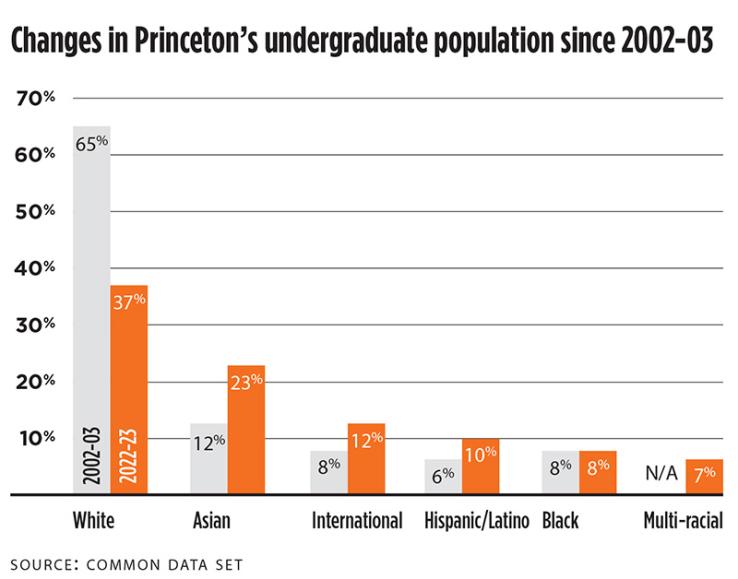

Two decades ago, when Princeton enrolled 4,635 undergraduates, the student body was 65% white, 12% Asian, 8% Black, 7% international, and 6% Hispanic. Last year, among 5,527 students, 38% were white, 24% Asian, 8% Black, 12% international, 10% Hispanic, and 7% multi-racial.

Princeton already is looking hard for talent at under-resourced schools that don’t typically send graduates to the Ivy League. The percentage of federal Pell Grant recipients, which target low-income Americans, surged from 7% for the Class of 2008 to almost 25% for the Class of 2023.

Admission to Princeton is a golden ticket for students who could not otherwise dream of attending one of the country’s top institutions.

Eddie S. Glaude Jr. *97, University professor and former chair of the Department of African American Studies, reacted with anguish to the Supreme Court decision, saying on MSNBC that he foresees a return to “a kind of segregated higher education landscape” with elite institutions enrolling predominately white and Asian students. Affirmative action was “the only remedy to the legacy of discrimination in admissions in American higher education … so here they’ve taken it away.”

“What the court has done is very bad. That there’s been such a backlash against such a modest reformist measure as racial affirmative action is quite sobering.”

— Randall Kennedy ’77

Harvard Law School professor

Robert P. George, founder and director of Princeton’s James Madison Program in Ideals and Institutions and McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence, applauded the ruling and says he does not believe it will “prevent Princeton or other colleges and universities from having diverse student bodies.” Assessing applicants as individuals, and not as members of so-called “overrepresented” or “underrepresented” groups, while considering the challenges they have faced “is likely to result in what will be in important ways a more diverse student body.

“There could be a broader mix of political, moral, religious, and cultural viewpoints than we currently have.”

Hamilton College President David Wippman ’77, a former law school dean, says he “was disappointed but not surprised” by the ruling. Hamilton is need-blind and accepted 11.8% of 9,899 applications for its Class of 2026. (Princeton’s acceptance rate for the Class of 2026 was 5.7% of 38,091 applicants.)

“Something that gets lost in a lot of discussions is people want to single out race as a single factor as having a dominant influence on the outcome of the admission decision. We really look at a large number of factors, whether that’s your SAT score, GPA, race, geographic origin, recommendations, and a host of other things,” Wippman says.

Now, under Roberts’ instructions, Wippman says Hamilton still can consider race not by itself but in an individually tailored way as opposed to a check-the-box way. “And I would say that we tried to consider it in an individual way in the past,” he adds. “Diversity will remain a priority. We just have to be very careful [how] we do it.”

Northwestern University accepted 7.2% of the 51,554 who applied last year. Its president, Michael Schill ’80, also a former law school dean, was “surprised and disappointed by the way the majority opinion devalued diversity as an objective.” Roberts wrote that Harvard’s claim it was training future leaders and providing a better education through diversity cited commendable goals but not coherent or measurable enough to warrant use of racial preferences.

Schill says he wished the court had treated the diversity issue “in a more serious way rather than just saying it’s sort of vague and subjective.”

The vast majority of the country’s 2,600 four-year colleges and universities admit a majority of students who apply, including private Willamette University, in Salem, Oregon, with 1,585 undergraduate students. Its president, astrophysicist Stephen Thorsett *91, spent five years on Princeton’s faculty in the 1990s and taught at the University of California, Santa Cruz before taking on the Willamette presidency in 2011. It admitted 79% of the 4,107 students who applied this year.

Only its law school made limited use of affirmative action, Thorsett says, but the high court ruling has impacted Willamette.

“It has led us to review other programs that included the use of race as usually one among a number of criteria, for example, in early college outreach programs,” he says, as well as endowments that have restrictions based on race or national origin. “We’ve been talking with donors and at times with the courts to revise those to bring them into alignment with what we knew was coming.”

In a state where 87% of the residents are white, “we’re about a third students of color,” Thorsett says.

“The thing that I worry about perhaps most is signaling to populations of students that have been historically underrepresented or excluded that in some way we don’t see them as important,” he says. “If there are voices in society making the argument that this isn’t important anymore, we have to be really strong in making that argument that institutions [such as Willamette] are for them.”

Princeton alumni voiced a diversity of opinions about the Supreme Court’s ban on affirmative action.

Mitch Daniels ’71, who recently completed a 10-year run as president of Purdue University, says, “I think everybody, by one means or another, has tried to find ways to recruit students who can diversify their student body, some by benign means and some by means that were very unfair.

“I don’t think the court could have come to any other conclusion. The discrimination was overt, obvious, and at a significant scale,” the former Indiana governor says. “It was hard to justify much of what was going on as consistent with [the 14th Amendment’s] equal protection.”

As a land grant school, Purdue is “deeply imbued with the mission of expanding access,” says Daniels, who froze tuition for a decade and expanded the student body by 30%. “We took all kinds of steps to recruit [minority] students aggressively,” he says, including launching three Purdue charter high schools in Indianapolis and South Bend emphasizing technology.

Harvard Law School professor Randall Kennedy ’77 and legal journalist Stuart Taylor Jr. ’70 are friends of long standing, but on opposite ends of debates over affirmative action. Kennedy made the argument for it in his 2013 book, For Discrimination: Race, Affirmative Action, and the Law. A year earlier, Taylor co-authored Mismatch: How Affirmative Action Hurts Students It’s Intended to Help, and Why Universities Won’t Admit It.

In a recent analysis of the Harvard-UNC decision in the London Review of Books, Kennedy wrote, “Racial affirmative action does have major drawbacks. For one thing, it puts a pall over the racial minorities assumed to be its beneficiaries.” But he argues that its scope was modest and its aims were commendable, even if they came at “steep costs” and adversely affected some white applicants with higher test scores and grades.

“Its termination at the hands of a reactionary Supreme Court is a significant setback,” Kennedy wrote. “Racial hierarchy in the U.S. remains a huge problem. The Supreme Court’s suppression of affirmative action calls into sharp question whether America has within it the moral and political resources to address satisfactorily that long-festering injustice.”

“What the court has done is very bad,” Kennedy tells PAW. “That there’s been such a backlash against such a modest reformist measure as racial affirmative action is quite sobering.”

Taylor, co-founder of Princetonians for Free Speech, which advocates for academic freedom and “viewpoint diversity” on campus, says affirmative action penalized Asian Americans as well as white students. He says he believes that Black students who benefited most “tend to be the children of recent immigrants and children of upper-class Black people, not descendants of slaves. Obviously, some are, [but] it’s very divisive.”

Taylor says it “would be terrible” if the number of Black students admitted to Princeton dropped by half — which is what Harvard predicted would happen to it — but doubts that will occur. He foresees more lawsuits ahead as universities seek to evade the ruling in “any way they can.”

“I don’t think the court could have come to any other conclusion. The discrimination was overt, obvious, and at a significant scale.”

— Mitch Daniels ’71

former president of Purdue University

Zavier Foster came back to school early to work at freshman orientation. “I’m seeing all the freshman people of color move in and it’s kind of sad because you just know that next year there’s going to be so many less,” he says.

Foster is from Baldwin, New York, the son of Jamaican immigrants. He chose Princeton from among 19 schools to which he won admission. He says he does not feel he benefited from affirmative action. If his grades, SAT scores, essays, and activities were put up against those of white classmates, “I think they would match or outshine them.”

“I can’t speak for every individual Black student about how they feel about their position here at Princeton, but I will say from the conversations I’ve had that no one thinks it’s a stigma at all. We’re all at the same place and all doing the same things,” says Foster, a politics major who envisions going to law school or business school.

Zach Gardner, the son of a pastor and a Chick-fil-A executive from Atlanta, is also a politics major who has gotten a head start on his planned career as a lawyer by interning twice for a federal appellate judge. He applied early and chose Princeton over the University of Virginia and the University of Georgia.

He says he feels right at home on a campus where political conservatives are a distinct minority among students and the faculty.

“Princeton is a wonderful place to be, especially for conservatives, because we have such an incredible group of people on campus and professors and institutions that are very welcoming to different viewpoints,” says Gardner. “Everyone that I’ve met at Princeton, whatever the race, religion, ethnicity, beliefs, ideologies, they all come across to me as perfectly qualified to be here.”

Gardner doubts there will be a big drop in the Black student population. “If it does, I think that’s a conversation to be had when the time comes,” he says. Regardless, “It wouldn’t change the legal reality that the admissions department simply cannot use race qua race as a factor in admissions.”

Christopher Connell ’71 is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C.