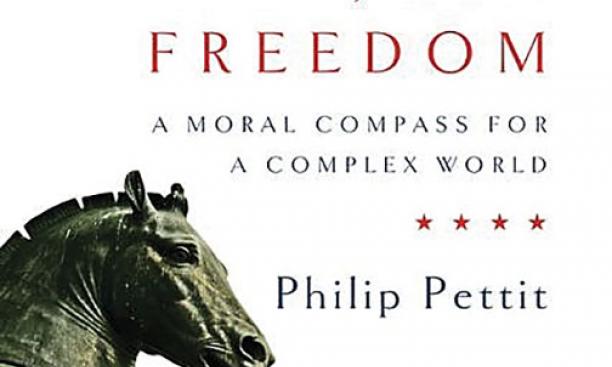

For Philip Pettit, the concept of freedom is more than just being “let alone” — that’s an impoverished idea of freedom, he argues, that doesn’t live up to the fuller sense put forward by Thomas Jefferson and other founders of American democracy. Countries that consider themselves free, including the United States, do not necessarily fulfill the idea of freedom Pettit espouses. To be truly free, he argues, individuals must be free of intimidation or control from outside forces and have access to a social safety net to ensure that they will not be dependent on others.

In Just Freedom: A Moral Compass for a Complex World (W.W. Norton), Pettit, a professor of politics and human values, lays out the philosophical underpinnings of what he calls the “republican” ideal of freedom, and looks at what society might be like if it adhered to these principles. A “republican” concept of freedom mandates that governments ensure the individual rights of citizens.

“If you hang on the good will of another, then you really don’t enjoy freedom in that original sense,” Pettit says.

Petit uses early American history to explain his ideal of freedom. The American Colonies, for example, did not want to live under a political system in which the British crown could subject them to taxes without their consent. It did not matter that the crown did not always interfere with the colonies in this way; the fact that it could do so was reason enough for revolt, Pettit says.

In his book, Pettit looks at freedom on three levels: among people, between people and their governments, and among nations. He proposes the “eyeball test” to determine if a citizen has achieved his definition of freedom: Can a person look another in the eye without fear of intimidation or rebuke? If not, then the person is not truly free.

This ideal of freedom requires a social safety net, Pettit contends. Without some form of social insurance, whether it’s medical aid or legal assistance, people are “left exposed, to be blown about by others,” he says. And governments must work to make sure they are representative of the people’s will: Electoral districts should be drawn up by nonpartisan panels, and officials should combat the influence of money in politics. Given these requirements, Pettit argues, the United States does not meet a republican standard of freedom.

Pettit is critical of international organizations like the United Nations, which gives greater authority to nations that sit on the Security Council. That restricts the freedom of smaller nations, which must abide by the decisions of the council.

“An international world that conformed to republican requirements would be a very different world from ours,” he writes.