When the first antibiotics were discovered 70 years ago, they were a medical miracle: Bacterial infections that once killed people in huge numbers now could easily be cured. But over the last several decades, the number of drug-resistant strains of diseases has been growing. Each year more than 2 million people in the United States are infected with “superbugs” that have developed resistance to most antibiotics, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and 23,000 of them die.

Pharmaceutical companies have had little incentive to develop new antibiotics, because the cost of research is high and the profits relatively small. The Food and Drug Administration approved 30 new antibiotics in the 1980s, but only nine in the last 15 years. In 2012, Congress passed legislation that could spur companies to develop new drugs by giving priority to new antibiotic applications and extending the period when antibiotics are on the market without a generic version. Two new antibiotics are under FDA review under the new law.

“The loss of useful antibiotics threatens our ability to practice modern medicine as we know it,” says Ramanan Laxminarayan, an economist at the Princeton Environmental Institute who studies antibiotic resistance and works with governments on policies to combat the problem. Not only do antibiotics treat existing infections, they make surgeries and other medical procedures safer by reducing the risk of infections.

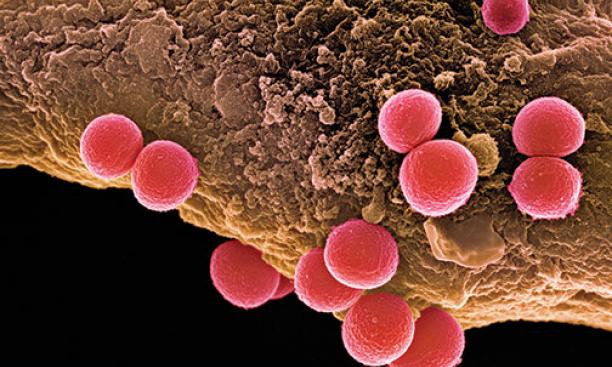

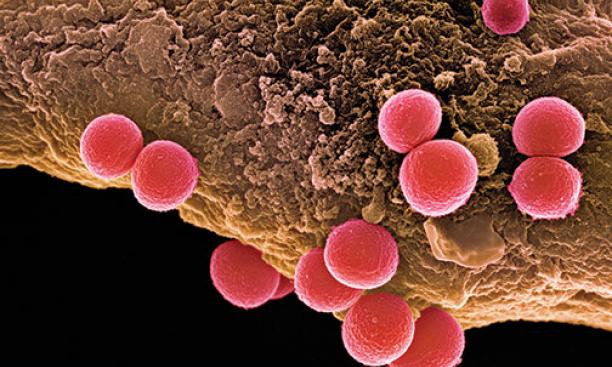

There are now drug-resistant versions of all bacteria that cause human diseases. For some particularly resistant strains, the only available treatments are extremely toxic antibiotics that can damage the liver and other organs. One of the diseases of most concern is gonorrhea: Each year in the United States there are some 246,000 cases that are resistant to all but the most powerful antibiotics, and some strains are not treatable at all — which can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease and put patients at a higher risk for HIV. Resistant strains of MRSA, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus — bacteria typically found in hospitals — have been increasing outside of health-care settings, causing a total of more than 11,000 deaths every year in the United States.

The main culprit for antibiotic resistance is improper use: The CDC estimates that 50 percent of antibiotic prescriptions are unnecessary or not prescribed in the correct dosage. Many patients expect to leave a doctor’s visit with an antibiotic prescription, and CDC guidelines that aim to minimize improper use often are disregarded, Laxminarayan says. He is collecting data on antibiotic use around the world to study patterns of resistance, including whether antibiotic-resistant strains found in farm animals in certain areas correlate with similar strains in people.

Agriculture is an important factor in creating drug resistance, according to the Centers for Disease Control. In the United States, about 70 percent of antibiotics are used on farm animals to prevent disease and make animals bigger, creating opportunities for pathogens to develop resistance. Last December, the FDA announced a plan for the voluntary withdrawal of some antibiotics from livestock feed, but Laxminarayan is skeptical that farm practices will change voluntarily.

Laxminarayan hopes that social norms about antibiotic use begin to change as the public becomes more aware of the problem. “People start paying attention when people start dying,” he says, “and many more people are now dying from bacterial infections around the world.”