Historian James McPherson is one of the nation’s pre-eminent scholars of the Civil War. In addition to his Pulitzer Prize-winning Battle Cry of Freedom, his much-cited history of the war, he has written more than 20 books on the conflict, most of them examining it from the perspective of the North. With his new book, he makes a 180-degree turn and looks at the Civil War from the perspective of the maligned president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis.

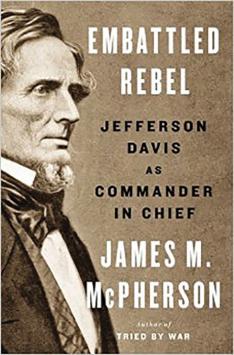

“This was kind of a void in my own scholarship,” says McPherson, a professor emeritus of history. Embattled Rebel: Jefferson Davis as Commander in Chief is a companion volume to Tried by War, McPherson’s study of Abraham Lincoln’s tenure as commander in chief.

The book is not a complete biographical study, but an analysis of the decisions Davis, a West Point graduate, made as the principal commander of the Confederate Army. What McPherson found was a man of “iron-willed determination” who, despite physical illness, worked tirelessly for the Confederate cause. “Davis’ strength as a commander in chief was one of the reasons why the Confederacy was able to hold out for four years,” he says.

McPherson found himself, somewhat to his surprise, empathizing with Davis. In addition to facing an opposing army larger than his own, Davis had to contend with critics from within the Confederacy, such as Southern governors who complained he was not doing enough to protect state borders.

Davis also was accused of micromanaging decisions instead of delegating them. These workaholic tendencies, McPherson suggests, may have contributed to Davis’ physical maladies, which included blindness in one eye. The Confederate president did work well with Gen. Robert E. Lee, whom he respected and frequently sought out for advice.

The ultimate military goal of the South was straightforward, McPherson says: “Winning meant only outlasting the North’s will to continue fighting.” Davis remained dedicated to that cause even while others gave up hope. By the fall of 1864, when Atlanta fell to Union troops and Lincoln won re-election, Davis perhaps should have “recognized the handwriting on the wall and tried to salvage something from the ruin, but that was not in him,” McPherson says.

Davis lived for another 24 years, but never recanted his belief in the Confederate cause or regretted the way he waged the war, McPherson says: “He was unreconstructed to the end.”

A War Brought Home: In his photographs of the Civil War, Alexander Gardner proved the power of an art form coming of age

Princeton in the Confederacy’s Service: 150 years after the Civil War, Rebel ties remain little-known

From Princeton’s Vault: Abe Was a Tiger