Anne Shaw spent only four years at the College of New Jersey, but her short employment signified an important shift in the makeup of Princeton’s staff.

Hired in 1877 as the assistant to the librarian, Frederic Vinton, Shaw is believed to be the first female employee to fill a non-service role on campus. That also made her one of about only 15 percent of American women who worked for pay in the 1870s. (PAW was unable to find an image of her.)

In Vinton’s letter requesting permission to hire an assistant, he noted that the position did not require “the strength of a man.” In fact, he specifically sought a woman “of mature age” to fill the assistant’s role, since “two such could be paid for the salary which it would be necessary to pay a man.”

Indeed, Shaw’s salary was a paltry $800 per year, while the librarian earned $2,800. Vinton had envisioned that Shaw, as his assistant, would do everything from alphabetizing his receipts to unpacking boxes of new books — and the “many other petty services” that occupied his time. But Vinton noted that Shaw turned out to be “just as competent” as he was to be the head of the library.

Vinton noted that two women “could be paid for the salary which it would be necessary to pay a man.”

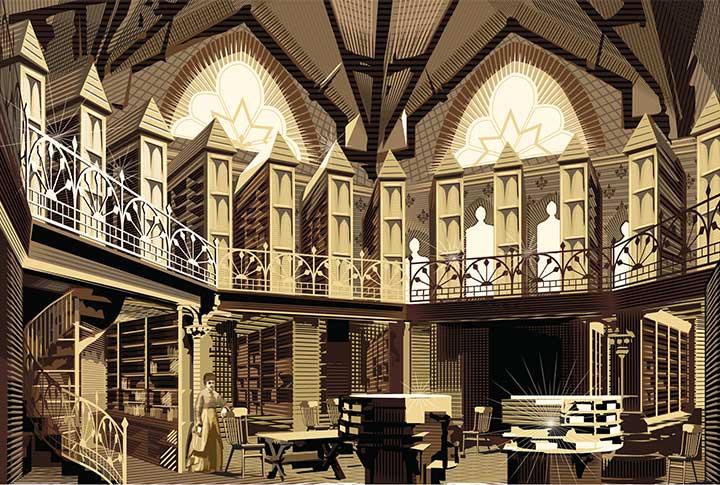

Born in Charlottesville, Va., Shaw had spent more than two decades teaching — despite her “perfect hatred” for the profession — because she believed it to be the “only occupation possible to an educated lady.” A cousin of John Shaw Pierson 1840, a major donor to Princeton’s collection of books on the Civil War, Shaw was over 40 when she began work at Princeton’s library, then in the recently built Chancellor Green. By that time, she’d lived in Europe for two years, traveling and serving as a liaison between her cousin and European libraries.

Vinton praised Shaw’s multilingual abilities, her depth of literary knowledge, and her good judgment. He believed the “work of mere routine and detail” was not befitting those traits. Instead, Shaw worked on creating the library’s first catalog, including an inventory of a newly acquired art collection. Another woman was hired as an assistant within the year, and with a staff of three, the library was able to remain open more hours each day.

Ultimately, Shaw quit in 1881 after four years because of poor heating in the library, which caused her to fall sick. Subsequently, she followed through on a plan she’d been dreaming of for years, launching a third career as the creator of a European tour company aimed at a female audience. Shaw called herself the “pioneer in the South of that profession,” and she shepherded groups of women around Europe on tours of four to six months.

By the time Shaw died in 1899, the library counted five women as assistants among its staff of eight. Still, 119 years went by after Shaw joined Princeton before a woman, Karin Trainer, would be named to lead the University’s library system.