The following story was published in the May 13, 1975, issue of PAW.

IN A RAIN so light I could hear it but scarcely feel it, I approached the Well of Death. Here 600 Mayans had perished as sacrifices to the god of rain, Yum Chac. Here Richard Halliburton ’21 had leaped—70 feet—to see what it felt like to be a human sacrifice, and escaped death with little more than a sprained muscle. I trembled because as I looked into the murky waters, green and brown and black and ominous, I wanted to jump too.

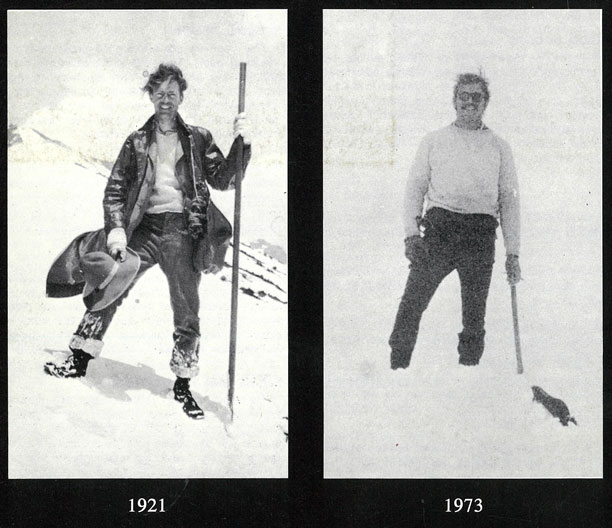

Halliburton had been a hero of mine almost from the first day I picked up a copy of his Royal Road to Romance. He didn’t just live life—he celebrated it. Or so it seemed in the vivid pages of The Royal Road and each of his seven other best-selling books. I read them all, in succession, marveling at the life this man had led.

READ MORE

What Would Halliburton Do?The life of a Princeton adventurer

He had swum the Hellespont and the Panama Canal. Crossed the Alps on an elephant like Hannibal. Climbed Mount Olympus, the Matterhorn, and Fujiyama “in the impossible season.” He had marched with the French Foreign Legion, suffered with the prisoners on Devil’s Island. He was jailed as a spy at Gibraltar, and bathed by moonlight in the waters of the Taj Mahal. For 18 years—the whole of his brief adult life—he did nothing but seek adventures, and earn his keep by writing and telling people about them.

By age 28, he was in Who’s Who. And by age 34, he was advertised in newspapers throughout the country as “the World’s Most Popular Non-Fiction Writer. ” He delivered some 2,000 lectures. Even his collected letters, written hurriedly from all parts of the world, became a best-seller after his death; the New York Times called it the best Halliburton book of them all.

“ ‘Live! Live the wonderful life that is within you;’ ” Halliburton loved to quote from The Picture of Dorian Grey. “ ‘Be afraid of nothing. There is such a little time that your youth will last. … Youth! Youth! There is absolutely nothing in the world but youth!’ ” And so he reflected in the first chapter of The Royal Road to Romance, “I had youth, the transitory, the fugitive, now, completely and abundantly. Yet what was I going to do with it? Certainly not squander its gold on the commonplace quest for riches and respectability, and then secretly lament the price that had to be paid for these futile ideals. Let those who wish have their respectability—I wanted freedom, freedom to indulge in whatever caprice struck my fancy, freedom to search in the farthermost corners of the earth for the beautiful, the joyous and the romantic.”

I liked Halliburton’s spirit. The whole of his life, he seemed to maintain a childlike openness to experience. From the day he left Princeton in 1921 to his disappearance at sea in 1939, he said he was striving for “the beautiful, the joyous and the romantic.” Moreover, he said his quest was worth it, that he found what he was looking for. But was he really like that? And was his life really as richly rewarding as he said it was? I had to know, for if it was, I wanted to live life the way he did: fearlessly, imaginatively, impetuously.

My chance to find out came during my senior year at Princeton. I had enrolled in Humanities 406, “Writing on Public Affairs,” taught by Ferris Professor of Journalism Irving Dilliard, the former editorial-page editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. I remember clearly what he told us the first day we met: “Use this course to write about something you’ve always wanted to write about but never had the chance to write about before.” Here at last was the opportunity I had been waiting for.

Where to begin?

Halliburton had dedicated The Royal Road to “Irvine Oty Hockaday, John Henry Leh, Edward Lawrence Keyes, James Penfield Seiberling—whose sanity, consistency, and respectability drove me to this book.” He described them memorably in the opening chapter: “I looked behind me at my four roommates bent over their desks dutifully grubbing their lives away. John frowned into his public accounting book; he was soon to enter his father’s department store. Penfield yawned over an essay on corporation finance; he planned to sell bonds. Larry was absorbed in protoplasms; his was to be a medical career. Irvine (he dreamed sometimes) was struggling unsuccessfully to keep his mind on constitutional government. What futility it all was—stuffing themselves with profitless facts and figures, when the vital and the beautiful things in life—the moonlight, the apple orchards, the out-of-door sirens—were calling and pleading for recognition. A rebellion against the prosaic mold into which all five of us were being poured, rose up inside me. … ”

Halliburton rushed off to realize his youth while he had it. But what of the other four? What had become of them and how did they recall their erstwhile roommate? It did not take me long to find out. From Princeton’s Alumni Records Office I learned that they were all still alive. I fired off letters to the four of them and anxiously awaited their replies.

Seiberling had long since become president of Seiberling Rubber Company, as well as a university trustee. Keyes was now, in his words, a “stuffy MD, moulding in retirement”; he had become a prominent surgeon in St. Louis. Leh was now a top officer in his father’s department store, the H. Leh and Company in Allentown, Pennsylvania, and he had been class secretary for over 40 years. Even Hockaday (“he dreamed sometimes”) had become an eminently respectable First Vice President of the firm of Harris, Upham, and Company in Kansas City.

Seiberling sent me 17 pages of recollections, as well as copies of speeches made at the dedication of a tower in Halliburton’s memory in Memphis, Tennessee. I was astonished. The one published biography takes Halliburton from birth to college in three-and-a-half pages, telling virtually nothing about his formative years. Here I had anecdote after anecdote from a man who had known him from his first year in Lawrenceville until the end of his life. And here too was the first clue as to why he had become the rather extraordinary individual that he was.

At age 15, Halliburton had developed a heart condition that forced him to lead a restricted life. When his younger brother Wesley reached 15, he too developed a heart condition. But Wesley died from it. Seiberling recalls the effect on young Richard, who was 18 at the time: “It made him very bitter about religious conceptions pertaining to the rationality, fairness, and compassion of God Almighty, and caused him doubt and skepticism as to whether there was ever or then in existence a Creator or Supreme Being of any kind. His beloved brother’s death was a supreme act of stupid senselessness. … I am convinced in my own mind that it was this tragedy in his life that caused him later to philosophically decide that as far as his life was concerned, he was going to devote it to experiencing all the goodness of human experience on earth that could be found, and that he would devote his mind and energies to such a search so long as he lived.”

Perhaps Seiberling was right. About this time, I found in one of the 16 cartons of Halliburton papers in Firestone Library an essay he had written as a senior at Princeton. Although the topic is supposedly Byron (the title is “Byron the Inspiring”), it tells us at least as much about Halliburton. Byron’s relatively young death and intensely lived life held a curious fascination for him: “How woefully few can face death with indifference and say, ‘Do your worst, Death old boy, I’ve LIVED, I’ve entertained every sensation—(every passion)—every thrill this world can offer. I crave different adventures. Show me what Hell has to offer!’ ... Byron LIVED. He crowded into 20 years of maturity enough to make 20 ordinary lives intense. How fortunate he died so young. Is life worth living after the unreasoned irresistible thrills are gone, after the fires are spent, after the unconscious adventure of youth has faded, —in other words after 35 or 40? When, without temptation, we must philosophize about morals, and reason out happiness through mental processes, when the power and vigor of life must be substituted by retrospection and regrets, isn’t death and a new start to be preferred. It is for me.”

Furthermore, Halliburton declares that man must have the “audacity to climb the Matterhorn, to swim the Hellespont, to play with fire, to make sport of the divinities on Mount Olympus.” In the next five years, he does all of these things. And in later years, he will proclaim that these early adventures were the realizations of his personal dreams, while cynics will charge that his romanticism was a pose and that his exploits were carefully thought-out stunts to garner publicity and earn big money. But here I found evidence that, at age 21, Halliburton was already intent on leading a life of adventure because he felt it was the only life worth living. He admired Byron for his indifference to convention, and for daring to live his life to the utmost. “Divinity offers everyone a LIFE,” young Halliburton wrote, “most men accept an existence.”

My search soon began turning up more new material than I could handle. Besides his roommates—all of whom responded generously—I contacted people who had been in extra-curricular activities with Halliburton at Princeton, club-mates, prep school friends, and others who knew him in later years. “He was a fabulous fellow,” wrote Lowell Thomas *16, noting, however, that there was “something sorta ‘la-de-da’ in his style.” A roommate from freshman year recalled, “He was kind of a gravy rider. He would accept favors from pretty near anybody.” He told how Halliburton’s roommates once had to plot to get him to pick up a dinner check.

Hockaday talked with me for over an hour long distance, relating, among other things, how Halliburton had grown weary of his life-style in later years. He told Hockaday that he was going to turn around and be “completely different” after the Chinese Junk expedition. In fact, he said it would be his last trip. As fate would have it, that was the voyage from which he never returned. I was intrigued as to why he had grown weary. Halliburton told Hockaday he was getting to the point where he kind of envied him.

Julien Bryan ’21 recounted his experiences with Halliburton editing the Princeton Pictorial Magazine. Bryan (who later became a highly successful lecturer and producer of travel films) once did “a story of how a classmate and I had shoveled coal one summer on a tramp steamer,” but Halliburton found it “unimaginative.” “He wanted it all exciting,” Bryan said. “He wanted me to embroider it. He didn’t care if it was true or not!” To which I could only add that in one of his college essays Halliburton had asserted: “Better by far … to be guilty of interesting lies, than to be guilty of stupid truths.”

Gradually I came to realize I was in a situation most scholars and writers dream of. I had a subject I was intensely interested in, about which little had been written, and sources of information previously untapped. I was getting first-hand recollections from people who had actually known Halliburton. Most of them were in their mid-70s, and if their stories were not recorded now, it would soon be too late.

I went to the deans of the college with a proposal to change my course of study, so I could do my thesis on Halliburton, and write about my old thesis topic in Humanities 406. Professor Dilliard agreed to advise me on both projects. But the deans turned me down. I was disappointed, for I knew I was onto something. Dilliard suggested I consider writing about Halliburton for publication. I decided I would try to gather material for a biography. And before long, it was time for graduation.

I NEVER INTENDED to go to Memphis when I did. It was summer, and I was on my way to Florida to visit friends Billy Heinz ’75 and Mark Anderson ’74, who were in diving practice there. But half-way down, I changed directions and headed for Memphis, Halliburton’s home town. I knew his father had given a Richard Halliburton Memorial Tower to the campus of Southwestern at Memphis, and I figured there must be some people in the city who had known Halliburton or his family. I meant to find them.

Since I had not expected to begin my research when I did, my first stop was a shopping center. I picked a white sports coat off a rack (it fit), bought a shirt, a tie, a small tape recorder, a notebook, and a few inexpensive pens. I was now equipped for researching a biography. I stopped next at the home of Jan Kubik ’70, a former roommate of my brother, Art. His family invited me to stay as their guest while I did my research, which saved me considerable expense.

At Southwestern I was given permission to examine all of the Halliburton materials on display. The glass cases were unlocked for me, and I looked through the fading copies of Halliburton’s many newspaper articles, his first travel journal, a few original letters, and mementoes of his trips. There was a variety of Princeton memorabilia as well: a roster of Cap and Gown members from 1921, old Nassau Heralds and Princeton Pictorials, an award from the Class of ’21 given to Halliburton posthumously, and his diploma. I found to my surprise that many of the items were improperly labeled (the diploma was identified as the Nassau Herald, etc.), and I quietly rearranged the cards in proper order. I knew Halliburton had done the same for the memorials of men he admired.

Then I photocopied everything I could: editorials Halliburton had written as a student at Lawrenceville, every page of his first journal, the old newspaper articles, everything. Fortunately, the college let me make the xeroxes at reduced rates. I knew Princeton had the major part of Halliburton’s original letters, but none written before 1925. I had hoped they might be at Southwestern, but when I asked I was told that everything the school had pertaining to Halliburton was on display.

One interview led to another. I was surprised at the ease with which I was accepted as a biographer. James Cortese, a columnist for the Memphis Commercial Appeal, spent many hours talking with me. He had been a friend of Halliburton’s father. “I don’t know why the old man gave me this,” Cortese said one night. “I didn’t especially ask for it.” And he pulled off a shelf in his study a large black scrapbook marked, “The Flying Carpet.” The Flying Carpet was not only the title of one of Halliburton’s books, but also the name of a plane in which he had flown around the world. The scrapbook was filled with newspaper clippings about that trip.

“There were about a dozen of these scrapbooks,” Cortese went on. “This was about the least substantial of them all.” A dozen scrapbooks! Where were they? Cortese had one. Princeton had another that Halliburton had kept in his youth. (The others his father had kept.) Southwestern had none. “I don’t know where they are, Chip. Maybe one of the cousins has them. … ” I was dismayed at the way Halliburton’s papers and memorabilia had been scattered after his death. Although I was pleased when Cortese let me borrow the scrapbook in his possession, I still wanted to locate the others.

At Memphis University School, successor to a prep school Halliburton had attended, I was allowed to look through the crumbling old record books and make photocopies of everything I could. There I was told, “We had an award Richard Halliburton won as a student here. But it was lost or stolen a few years back.”

I left for Florida.

FROM FLORIDA it was only a short plane flight to Mexico. Of all Halliburton’s fabulous adventures, none had intrigued me more than his encounter with the Well of

Death. I had to see it. I had read everything I could find by or about Halliburton. I had talked to people who had known him and his family. But I felt if I was going to truly understand the man, I had to go where he had gone, see what he had seen.

I got off the plane in Merida, a little scared and very excited. I was by myself, I spoke not a word of Spanish, and I did not have much money. I took an inexpensive bus to the ruins at Chichen Itza, where, 45 years before, Halliburton had risked his life “to see what it felt like to be a human sacrifice.”

I had read Halliburton’s description of this sacred place a thousand times, but still I was not prepared for the startling bone whiteness of the vertical limestone walls, or the absolute blackness of the caves and hollows that riddled one side of the well. I knew what I wanted to do. I stood by the edge, trembling a little. Yet something held me back, and in the rain I waited. What I was waiting for I did not know.

Then, from over a small hill came an American father and his family. He was doing his best to describe the wonders of Mayan civilization to his children. Recognizing these people, I smiled. We had come on the same plane together.

I explained to them that I was on the trail of Richard Halliburton. He had jumped in here, I was writing about him and wanted to know what he felt. And would their older son hold my camera? “He’s not really going to jump?” the younger daughter asked her mother. “Don’t do it!”

With these few people around me, I removed my shirt, tried nervously to muster a smile, and—stepped out.

Suddenly there was nothing below me.

I felt free!

The walls rushed up past me. I didn’t look down. For an instant—sailing through what seemed endless space—I was Halliburton. Then my body, tense and rigid as I leaped, turned to jelly. I couldn’t control it. I was terrified.

And then I hit! How soft and warm and dark the water was. It goes down some 40 feet, and I tried to see as little of it as possible. Finally my head burst through the surface and I shouted up: “I’M OK. I FEEL GREAT!” Great? I felt ecstatic!

I was laughing and grinning in the water. Never had I felt more wondrously and joyfully alive. My voice—healthy and booming—was echoing back and forth off the 70 feet of cylindrical rock walls. It didn’t even sound like my own any more, but more like a god’s. No wonder Halliburton liked this place.

Climbing up was no easy matter.

I struggled painfully to rise from one tiny ledge to the next. I searched for handholds, footholds, toeholds in the crumbly white rock. Great handfuls of limestone dust came down every time I reached over my head. After an hour, I was about 40 feet up and fairly covered with a dull white powder. I looked like a mummy.

Then I froze and shouted with horror: “Oh my god! There’s the biggest nest of bees I’ve ever seen in my life.” One of the yawning black openings in the shadows on the wall contained a massive hive. The bees’ droning filled the air. I was amazed I had not noticed it before.

Slowly, carefully, I crawled back on a narrow ledge to a tiny cave in the rock. I was fearful, yet exhilarated. It was exciting risking my life before all those people. (By now a crowd of 50 or more had gathered at the top.) “Somebody get a rope!” I shouted. The father of the American family ran off for help.

The next words I heard were not exactly what I had been waiting for: “You’re on federal property. This is a federal offense.” I was further advised that I could just sit there for three hours before a rope would arrive. And even when it did come, it would not be able to reach me because the rock jutted out over my head.

Soon, however, the Federales came, rope in tow. I jumped in again, swam to where the rope could reach me, and—scraped, bruised (but so elated I was oblivious to the pain)—I was pulled out.

The Federales told me they could give me a year in jail. I had broken some unwritten law. I told them I had not meant to break any law. It was just that I was writing about one Richard Halliburton, and 45 years ago he too had jumped into the well.

“Do you know why I like Richard Halliburton?” the head guard asked me. Surprised, I said no. “Because he is a good writer. I have his New Worlds to Conquer. I have his Royal Road to Romance.”

Then he directed me never to write about what had happened that day. There were snakes and sunken objects in the well. Although no one else (other than Halliburton) had jumped in the well, workmen on an archeological expedition had died there. It was not a safe place. Then he released me and I walked out into the town.

It was a beautiful day.

Jumping into the well changed me. I could not just go back to the hotel and see Mexico as a tourist. I pulled my copy of Halliburton’s New Worlds to Conquer out of my back-pack in the hotel, and plotted where I would go next. For the rest of that summer, I stayed on Halliburton’s trail.

Not long afterwards I was buying my first pair of mountain-climbing boots to ascend Popocateptl as Halliburton had. The mountain is not technically difficult, but the rarity of the air at that altitude was more than I had reckoned with. Still, leaving a hut at four in the morning to climb by moonlight was every bit as surreal and romantic as Halliburton could have described it.

Yet when I reached the top six hours later—so breathless I was now taking four breaths before every step—the snow filled the air in a “white-out,” and I could see nothing at the mighty summit. “Damn you, Richard Halliburton. Damn you.” I kept saying over and over again softly. My companion rushed back almost immediately, but I lingered at the top to commune with the spirit of my mentor.

Another memorable experience occurred in Peru. Halliburton had described the wonders of Machu Picchu, the hidden city of the Incas to which 100 sacred sun virgins were spirited away when the Spaniards came. The city remained unknown to civilization until 1911, when a professor from Yale, Hiram Bingham, discovered it. Halliburton had ended his chapter on Machu Picchu with a passage about the sun god throwing his supremest gift, a “bewildering double rainbow” across the heavens. I took this to be poetic license but could not fault Halliburton for it. It was one of his most beautifully told stories.

I persuaded two Americans I met in Lima to come with me to Machu Picchu. We traveled overland by train, bus, and finally by small plane for two weeks until we got there. Then we climbed to the site much as Halliburton had. The view was magnificent and mysterious. As we reached the altar, the so-called “place where the sun is tied,” a strange thing happened. It began to rain, gently and not unpleasantly, just as it had when Halliburton was there some 45 years before.

“Take a picture,” I suggested to one of my friends. “I think there’s a rainbow forming.” There was, and I pulled out my well-worn copy of New Worlds to Conquer to read a bit from the chapter about Machu Picchu. And while we were sitting there in the light rain, a second rainbow formed above the first. Never before in my life, and never since, have I seen a double rainbow. But at Machu Picchu, where Halliburton said he saw one, we did too. It seemed almost like an omen to go on with the research.

On the way back in the train, the three of us kept repeating a line from New Worlds to Conquer that had become a catch-phrase for us: “No, Machu Picchu did not disappoint me.”

EVENTUALLY I came back to the U.S. I found I was too deeply absorbed in my research to even think of doing anything else. So I checked through my xeroxes, noted the names of more people with whom Halliburton had attended school 60 years ago, and returned to Memphis to find them. Then I went to Florida to interview a first cousin of his; she had much memorabilia but no letters or scrapbooks.

After losing some months’ time recuperating from an automobile accident (in tranquil Princeton, of all places), I spent most of a spring, and all of a summer, sifting through the 16 cartons of Halliburton papers in Firestone Library. To my surprise and amazement, I discovered his letters had been highly edited (doctored would be a better word) by his father before publication. Lines were changed, deleted, added. Not all of Halliburton’s adventures took place as he described them. For example, he wrote that he had bought and sold slaves in Timbuktu, when in reality he had left the city in a rush to escape the flies. The slaves were an afterthought, a story he tried out on reporters at his hotel suite in Paris. They loved it.

I found a whole new level to Halliburton’s life in the letters, periods of great unhappiness, near-suicidal depression not hinted at in his published writings. He had made a conscious decision early in life to present the good side of things and he kept to it. He finished the manuscript of his first book in a sanitarium, the second hidden away from his friends in a New Jersey hotel. Gradually the emotional turmoil that marks so many of his early letters diminishes. Yet curiously as Halliburton’s own life seems to become more calm and stable, much of the “joyous wonder” goes out of his writing—something he himself is aware of.

(The more involved I became in his life, the more difficult it was to extricate myself from it. I suffered reading of his sufferings. I grew elated reading of his moments of elation. How else could I react after living with his thoughts for so long?)

There were times when Halliburton grew cold and hard to the world. One of my favorite quotes from the published letters reads, “My affections are starved.” But the original reads somewhat differently: “My affections are absolutely dead.” I discovered this and other discrepancies while comparing the published versions with the originals in the Princeton collection. The library has every letter Halliburton wrote to his parents from 1925-39 except for one.

The published version of the missing letter, even though presumably as highly altered as the others, leads one to believe that it was quite significant. In it Halliburton speaks of his need for solitude, his changing attitude towards life (and the resulting change in his writing style), and the fact that he is building a house in California for himself and a companion, Paul Mooney.

Mooney’s name appears frequently throughout the original letters, yet almost not at all in the published versions. If Halliburton, Mooney, and a third man do something, Halliburton’s father will cross out Mooney’s name and leave the other. If Mooney and Halliburton are shopping together in the original, Halliburton is shopping alone in the published version. Halliburton's father crosses out Mooney’s name virtually every time it appears, with great forceful horizontal and vertical pencil lines. It is as if he did not want Mooney to have existed.

It would be helpful to have letters written from Halliburton to Mooney, but it is doubtful that any still exist. Preserved in the original letters of Halliburton to his parents is a line telling his father that he has asked Mooney to destroy the letters he had written him. Mooney vanished with Halliburton aboard the Chinese Junk.

I COMPILED a list of the names of every person Halliburton mentioned in his letters (and the way in which they were mentioned) and set out once again to find them. I located people whose names were on old party invitation lists and mentioned casually or repeatedly in letters to his parents. I spent almost two months in Tennessee and other parts of the South, talking to people who knew Halliburton and locating written material. I also found time to give a couple talks at private schools on the irrepressible adventurer and my research.

Finally, following the suggestion of Halliburton’s former roommate Leh, I obtained a copy of Halliburton’s will. It specified that all of his belongings were to go to Princeton, for the creation of a Richard Halliburton Geographical Library to be devoted to books on travel, geography, maps, charts, etc. Halliburton’s estate would be held in trust, however, until both of his parents had died.

I grew excited. Halliburton’s father had outlived his son by more than 25 years. Perhaps in that time the provisions of his son’s will had been allowed to be forgotten. I obtained a copy of the father’s will. Sure enough, it itemized all the belongings Halliburton's father was giving to Southwestern: Halliburton’s bound volumes of the Princeton Pictorial, the Lawrence, the magazine articles, his watch, several awards, and—the 10 missing scrapbooks.

I called again upon Southwestern and was told a search would be begun for the scrapbooks. A few days later, I received word that they had been found, and I could see them in the morning. I tried to sleep but couldn’t; I felt like a small boy on the night before Christmas.

Finally it was morning. The librarian at Southwestern, Albert Johnson, wheeled out a cart containing 10 large black scrapbooks. “I think you will be pleasantly surprised,” he told me. The scrapbooks were stuffed with every kind of newspaper article by or about Halliburton, cartoons from all over the world showing the extent of his fame as he crossed the Alps on an elephant in 1935, photographs of Halliburton’s friends—meaningless unless one had read the letters, but people I felt as if I knew—telegrams marking the highpoints of Halliburton’s career. This treasure had been placed in storage with the entire family library that Halliburton’s father had given the school, and with the passage of time it was forgotten that the scrapbooks were there. “We did not know we had them,” Johnson said.

I was too excited to care.

I asked if I could see the books Halliburton’s father had left to the school. It seemed almost too good to be true, but the collection had not been disturbed since the day it was received. There on shelf after shelf were the thousands of volumes Halliburton, his mother, and his father had read. I could see the books that had formed his mind: a wide variety of titles on geography, history, and travel; old editions of Stoddards’s lectures and child histories of ancient Greece. There were even a few volumes Halliburton had taken from the Princeton library some 50 years before and never returned. He had written that he was not above stealing a book if it suited his purposes, and here was proof.

I opened every volume, looking for margin notations, telegrams, letters stuffed between pages. I had been taught that thoroughness pays and it did: in one of the books I found four old $10 bills, placed there and forgotten decades ago.

Southwestern let me xerox whatever I wanted from the scrapbooks and Halliburton family library, and even let me take a few of the books on loan. I left a happy man.

Today I sit in my room with a dozen of Halliburton’s own books, some 3,000 xeroxes from the scrapbooks alone, countless tape recordings of interviews, and 30 or more notebooks filled with my illegible scrawl. I still have a few loose ends to tie down. I have to go out to California before I am done to see the people Halliburton spent his last years with. And there is a relative or two left I haven’t talked to. But I am finally ready to begin writing that book.

No responses yet