Often left out of the discussion of Woodrow Wilson 1879’s policies on race as president of the United States is the fact that there were many more people urging Wilson to keep the country segregated than to stop segregation, said Wilson biographer A. Scott Berg ’71, one of four scholars who spoke on an April 9 panel about Wilson’s legacy. Additionally, before he took office, many Southern congressmen told Wilson he would not get any bills passed if he allowed the integration of government offices to continue, Berg said.

“I don’t think he was a hater,” said Berg, who went on to say, “Yes, he was a racist.” Berg, a University trustee and a member of the Wilson Legacy Review Committee, said that “during his presidency, Wilson kept the race conversation going. ... I think Wilson knew when he got into office that race was going to have to be dealt with, and I think he wanted more than anything else for it not to be on his watch.”

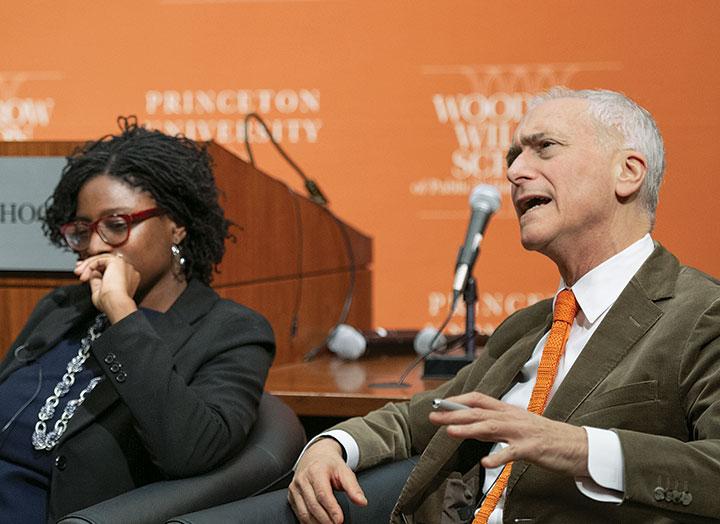

Other scholars on the panel, sponsored by the Woodrow Wilson School, included Chad Williams *04, associate professor and chair of the Department of African and Afro-American Studies at Brandeis University; Eric Yellin *07, an associate professor of history and American studies at the University of Richmond; and Ashleigh Lawrence-Sanders, a Ph.D. candidate in the history department at Rutgers University. The event took place four days after the announcement that the trustees had decided to retain Wilson’s name on Princeton’s public-affairs school and on one of its residential colleges.

Yellin, who will teach a course at Princeton in the fall called “Woodrow Wilson’s America,” said that when Wilson campaigned as a progressive candidate, he said he had “the best of hopes for everyone — including African Americans.” After he assumed office, Yellin said, Wilson justified the segregationist actions of his administration by promoting the idea that segregation was in the best interest of all Americans because friction between the races could cause issues in

the workplace.

“That’s a progressive, bureaucratic justification that we see again and again,” Yellin said. The result, he said, was “an erasure of 30 years of African Americans serving the nation at all levels of the federal government.”