PAW contributor Alexandra Markovich ’17 is a member of the women’s cross country and track and field teams. This story was adapted from a feature written last year for Professor John McPhee ’53’s journalism course, “Creative Non-Fiction.”

On Oct. 30, 2009, in the southwestern corner of Van Cortlandt Park, a gun goes off. All of a sudden, 94 young women are stampeding. The pack runs north across the flats, does a loop, running 10 or more wide beside Broadway, and funnels into the cowpath, a narrow, sandy patch that leads to hilly dirt-packed trails.

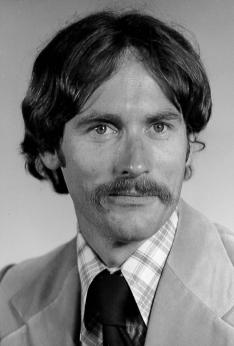

The cowpath marks a mile into the 5-kilometer race. After the mile, the hills begin. Peter Farrell, tall and dressed exclusively in Princeton Nike, is looking at his stopwatch. Every year since 1980, when Van Cortlandt Park began hosting the Women’s Cross Country Ivy League Heptagonal Championships (the Heps), Farrell has stood at the mile-mark of the 5k on the last Saturday of October. Long before women raced here at all, Farrell ran Van Cortlandt’s trying hills almost every fall Saturday during his high school cross country career. And before that, Farrell watched his brother, Tommy, four years older, run Van Cortlandt, too. The course is not made for spectating, and all you could hope to see are the starting lap on the flats and the bridge overlooking Henry Hudson Parkway.

“My routine is the same every time we go to Van Cortlandt Park,” Farrell told me in his office in Jadwin Gym years after that race, drawing an imaginary spectator’s map in the air. After the runners pass the mile mark, Farrell walks up the first hill, crosses the bridge, and waits at the top of what will be the last, and most difficult, uphill on the course. “It’s like watching a baby being born,” he says. “’Cause they leave you, and they’re gone for 10 minutes.” The women are out of his sight for over half the race.

Three women dressed in Princeton orange and black run past Farrell. Princeton has one, two, and three, and Harvard, Princeton, and Princeton are fighting for four and five. Princeton will win the title, Farrell is sure, but the cards have not all fallen into place. No team in the history of the Ivy League has ever won the Heps with 15 points — a perfect score. (The first five runners score for the team — first place earns one point, second earns two points, and so on. Cross country, unlike track and field, is won with the lowest number of points.)

When all the Princeton women have again passed, Farrell begins to walk toward the finish line, crossing the bridge, shuffling downhill. The race ends, but he doesn’t know the score. He bumps into the man who founded Cornell’s varsity women’s track and field program in the same year that Farrell founded Princeton’s — he is here to watch the meet, already retired — and the pair “old-time it while walking toward the finish line.” When they are half a mile away from the line, a guy on the Princeton men’s team whose name Farrell doesn’t know, jogs by and says to him, “That was awesome.” Farrell turns to his friend: “We swept.”

Farrell learned the details later. On the straightaway — an 800-meter straight-shot to the finish that drags on like no other half mile could — the Harvard runner passed Reilly Kiernan ’10 and then Ashley Higginson ’11. Higginson put herself in front of the Harvard runner. And then Kiernan “willed herself past her” to finish fifth.

Princeton earned one more Heps title at Van Cortlandt Park in 2010 before the meet moved to West Windsor Fields in Princeton. For the next four years, the Heps title eluded the Tigers. In 2015, the meet moved back to Van Cortlandt Park and on the last Saturday of October, Elizabeth Bird ’17 outkicked Dartmouth’s Dana Giordano on that same long straightaway to become the Ivy League Champion; Emily de La Bruyère ’16 and Kathryn Fluehr ’16 were not far behind in fourth and sixth to claim low scores. Princeton won Farrell his 27th and last Ivy League championship title on the same course he competed on all his life. After the race, Farrell was unanimously selected the Ivy League Cross Country Coach of the Year. At the end of the track and field season next spring, Farrell would close up shop, retiring after 39 years as head coach.

Since founding the varsity women’s cross country and track and field programs at Princeton in 1977, Farrell has been the program’s only head coach. With the perfect score in 2009, Farrell became the only coach in Ivy League history to sweep the cross country championships. He is also the only coach to win the cross country, indoor track and field, and outdoor track and field titles in one year: Princeton won the coveted Triple Crown in 1980-81 and again in 2010-11.

In a speech following the first day of competition at his last and 117th Heps meet, Farrell reminded the squad that a “last Heps” is something special. He singled out the seniors in the room to make the point that it was their last Heps as much as it was his. A last Heps is an opportunity for a senior to catch fire, Farrell said, and, as he always does, offered a story as evidence. In 2006, Cack Ferrell ’06, who holds Princeton’s second-highest finish at NCAA cross country at 10th place, was running the last lap of the 5,000 meters in second place. According to Farrell, the runner thought to herself, “My last Heps memory cannot be the back of someone else’s jersey.” She took home a title in the 3,000 and the 5,000 that weekend.

“We’ve won it by a point, we’ve lost it by a point, I’ve lost by half a point, I’ve tied,” Farrell told FloTrack at the end of the competition on Sunday. After 117 Heps, little can surprise him. But after every championship, he adds a story to his collection. Farrell is a living archive of women’s distance running at Princeton: the entire institutional history of Princeton women’s track and field is housed in his memory. He remembers every woman he’s ever coached, what she ran, what she studied, and something embarrassing about her. When I met Farrell for the first time on a visit to Princeton, he recalled the name of the last alum from my high school who ran for him (for one season, in 1986), and her motto (“Above all else, look good.”). The alum happened to be my best friend’s mother.

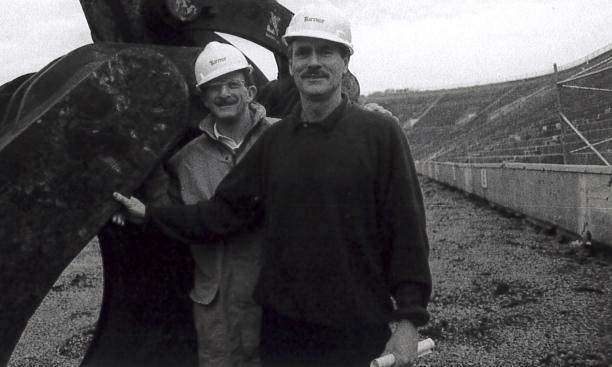

At the end of his final outdoor Heps, Farrell posed for photos near a steeplechase barrier that had been taken off of the track. Behind him in the stands, former athletes, starting from his first recruiting class, stood watching. His wife, brother, and youngest daughter surrounded him for photos. And later, when Farrell summoned the graduating class of 2016 to his side, the women held him up on their shoulders; he held up peace signs. Farrell told the team that he was honored by the attention, but what impressed him most was the same thing that impressed him 39 years earlier — the passion for competition that his women bring to the Heps.

Farrell has lived in Princeton long enough to see two lifecycles of the Brood X periodical cicada, which spend 17 years underground before emerging in perfect synchronization for a few short weeks of life. The first time, in the middle of May in 1987, the end of his ninth year of coaching, Farrell began to notice coin-sized holes in the ground, five inches apart, making “Swiss cheese,” he said, out of his backyard.

At the time, still a single man, he lived in faculty housing by Princeton’s golf course. When the cicadas emerged, they came out of the ground all at once. At 100 decibels, the mating call of the male cicadas singing in chorus is as loud as a jackhammer, or a jet taking off if you were standing 300 meters away. Farrell’s friends told him that the last time the cicadas had sung at Princeton, the Class of 1970 was graduating and Bob Dylan was being handed an honorary Doctorate of Music. Bob Dylan wrote “Day of the Locusts” after listening to the cicadas’ song.

The next time the cicadas emerged, Farrell was living in a two-story home on Patton Avenue — a five-minute drive from the track — with his wife, Shane, and two daughters, Virginia and Susan. By the end of May in 2004, when the cicadas were emerging again, Virginia got into the habit of leaving the house carrying an umbrella to ward off falling cicadas. A week after that, she could leave the umbrella behind, but each of her steps was met with a loud crunch.

“What brought you to Princeton?”

“What? You take Route 1.”

Farrell came to Princeton after teaching high-school American history for nine years in Middle Village, N.Y., at Christ the King High School, where he established a girls’ track program. He had taken a break from running two years after graduating from Notre Dame in 1968, and it didn’t take long for him to miss it. Running, he said, especially distance running, is “all-encompassing,” which makes it hard to do and harder to leave behind. Running had transformed Farrell, once a “shy, timid kid,” into an athlete — goal-oriented and confident. “Why not see if a girl could get out of the sport what I did?” Farrell had asked himself.

After interviewing at Princeton, which he immediately considered “a place you could bury me at,” Farrell showed up to work on Sept. 1, 1977. On that day, he bought a pet tiger rock at the United Methodist Church of Princeton. Farrell used to take the tiger rock to cross country meets and the girls would pass it around, each touching the rock before a race. The tradition has since fallen by the wayside, but Farrell has held onto the pet tiger rock, along with “a lot of sentimental stuff,” in his office, the same one he has had since that first day.

Farrell adopted the women’s club running program, which had been coached by Bill Farrell (no relation) the previous year. Farrell bought uniforms from the University Store — orange T-shirts with a tiger’s face on the front and the tail on the back — and set about getting the women into cross country and track meets. It was 1978 when he petitioned Penn Relays, the oldest and largest track meet in the country, to allow collegiate women to compete in the meet for the first time. At Farrell’s last Penn Relays this spring, Mondschein said he had “a line of people waiting to thank him,” a testament to his role in developing women’s collegiate track and field. When Mondschein walked with Farrell around Franklin Field, they stopped often so coaches and former athletes could share their gratitude with the veteran coach.

The team was small and Farrell thought he did not have enough to do. He briefly took up squash, a game with an objective he describes as dishonest — repeatedly putting the ball where your opponent can’t get it. But mostly, Farrell spent his first year recruiting. He spent Monday mornings in Firestone Library reading the Cleveland Plain Dealer, the St. Louis Post Dispatch, the Dallas Morning Herald, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Chicago Sun Times, the Atlanta Constitution — papers all around the country — looking for high-school girls’ results. He started sending letters out.

“Penn and Harvard hired around the same time, but they weren’t as aggressive as a young guy’s gonna be,” Farrell told me. Farrell’s letters and “aggressive” recruiting early on brought him Heps titles in 1978, ’79, and ’80; by ’81, the rest of the Ivy League started catching up. Behind him on his desk is a photograph of a white-haired Betty Costanza, the founding mother of Penn women’s track and field, sitting between Farrell, similarly white-haired, and Mark Young, who began coaching at Yale in 1980. It was Mark Young who would “save” Farrell at a Houston bar on the last night of a coaching convention by telling him which side of the room to sit on: “If he’d said turn right instead of left, I never would’ve met Shane, and I’d still be a free man.” After a period Farrell describes as “courting,” Shane moved to Princeton and then got a job at the University.

Farrell’s first recruiting class, entering in the fall of 1978, would be one of his best. “My first recruit was the best runner in the world,” Farrell told me. Lynn Jennings ’83, a Princeton native, won a bronze medal in the 10,000 meter race at the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, the first American woman to win an Olympic medal in distance running on the track. When Lynn Jennings ran a hard workout — four 1-mile repeats at just over 5-minute pace — Farrell ran each mile at her side.

In two file cabinets at the back of his office, Farrell keeps the written records of every workout the team has run, the splits of every race, and all the recruiting forms before the mid-1990s, when it went digital. Though he still records workout times, he stopped running alongside the women when he turned 50. When the team runs mile repeats now, Farrell bikes from mark to mark, calling out splits. Mike Henderson has taken over the running and Farrell has turned to morning aqua-jogging for exercise. “I hope they give me a lifetime pass to Dillon [Gym],” Farrell joked.

Farrell’s first recruiting class made its Heps debut in 1978 and earned Princeton women’s cross country its first Heps victory. Jennings came in first for the team and second overall to a runner from Harvard. Eve Thompson ’82 finished fifth in the race and third for Princeton. In a message that was played as part of a commemorative video at Farrell’s final team banquet at the Nassau Inn, Thompson told a story about her first day at practice. When Farrell asked her if she had been running since arriving on campus, she told him she had run by the river, to which Farrell replied that it was, actually, a lake. “Farrell, you’ll be happy to know that I now know the difference between a river and a lake,” Thompson joked in the video. Farrell interjected to compliment his former runner, explaining to the audience that Thompson helped draft the South African constitution after apartheid, as Thompson’s voice continued on the screen. “And I want you to also know that I’m very proud to have been among your very, very first team of recruits. The dream team, I call it,” she said.

Nina Zollo ’82, who would go on to become team captain her senior year, finished eighth in the Heps that year. Farrell saw Zollo again about two years ago when she arrived in Farrell’s office all the way from Florida to support her goddaughter, Melinda Renuart, on her first visit to Princeton. (Renuart, now a rising junior on the team, finished third for Princeton at the 2015 NCAA Cross Country Championships, helping the team to a 21st-place finish.)

Fannie Cromwell ’79’s appearance at the 1978 Heps would become a favorite Farrell tale. Cromwell, a squash player turned distance runner, finished fifth for the Tigers in the Heps in 1978 and never ran cross country again. According to Farrell, a few months earlier Cromwell had come to cheer on her roommate, Weezie Sams, at the first cross country meet of the year, and complained to Sams afterward that she was cheering her on, but she wasn’t running any faster. Weezie, offended, told Cromwell she should try it herself — and she did, finishing 10th overall to cap off Princeton’s victory at the Heps in 1978 at a low 29 points, and then happily returned to squash.

Farrell did not talk about retiring much, but when he did, he laughed about it with his coaching staff. He had two jokes. “Why would I retire? Mike does 85 percent of my job,” referring to Mike Henderson, Princeton’s equipment manager and Farrell’s right-hand man. The second: “If I die tomorrow, Princeton will find somebody better, so you better hope I die in my sleep.” Henderson classified Farrell’s humor as one part gritty New Yorker, two parts Irish storyteller.

In typical Farrell fashion, he announced his retirement to the Princeton athletic department by pretending to stab himself with a fork. “What’s the cliché?” he asked the crowd at the department meeting until someone got the gag. “Stick a fork in him, cause he’s done.”

“Farrell’s a real wise guy. He’s a typical Queens/Long Island guy,” said Fred Samara, head coach of the men’s team, who walked onto campus the same day as Farrell in 1977. Though Farrell can be a jokester, “he expects excellence from his athletes and knows how to get that in the right way,” Samara said.

At the athletic department meeting, Farrell gave several reasons for his retirement. “You know it’s time to retire when…” Farrell began. He recounted a note one of his athletes had written for him: “Thanks for being our rock. You can’t hear us, you rarely respond to us, and you quite often trip us.” Second, he recalled that two women at practice were horrified to realize that the candidates for the presidential election were older than their coach. Is their memory better than Farrell’s?, they worried. Finally, he shared his experience cheering for the women lately: “Go Jen—Ali—oh Meli—Mela—!” When you start mixing them up, it’s time to go, Farrell quipped.

When he announced his retirement to his team, he told us it was “just time.” “My wife and I are going to walk into the sunset together. She’s retiring too,” Farrell told me later. He insisted he was not retiring after anyone in particular graduated. “Coaches always do that—I’ll leave after this kid of that class graduates. I did not want that to be the criteria,” Farrell said. “There’s going to be a strong team next year. I had to just say — now.” Farrell’s first national champion — hammer thrower Julia Ratcliffe ’17 — will return to Princeton next year after taking the year off to train for the Olympics, as will All-American distance runner Megan Curham ’18.

Farrell told me he was retiring for his family. “I haven’t had a weekend off in the fall since 1973.” Farrell is indebted to track for helping him meet Shane, and to the team for encouraging him to marry her. At a team banquet held in his apartment in 1988, the women bought a cheap, plastic ring, handed it to him in a jewelry box, and said, “Well?”, encouraging him to finally pop the question. Farrell jokes that his wife “had no idea what she was getting into” marrying a track coach, referring to a lifestyle that would, albeit happily, revolve around the track seasons. “We even planned our family around my occupation. My kids were born in the summer for a reason,” Farrell said.

Though Farrell does not know what he will do at 3:45 every day, he looks forward to spending more time with his wife and two daughters. This fall, Farrell made use of a cross country meet in Wisconsin to visit his eldest daughter, eating out before the race with Virginia and the seven-person travel squad. An old, framed school photograph of Virginia — wearing thick glasses, smiling wildly, her hair tied with a scrunchie — stands on a shelf above Farrell’s desk. Virginia has my sense of humor, Farrell said, explaining that the school photograph was intended to be a joke.

Over the phone, Reilly Kiernan, who used to race for Princeton wearing orange-and-black striped knee-high socks, told me she was “notoriously slow-twitch.” After Kiernan passed Harvard’s Claire Richardson to top off the women’s 15-point sweep at Van Cortlandt Park in 2009, Farrell would tease her, saying, “For the first time ever, Kiernan out-kicked someone!” The sweep, Kiernan told me, could only ever be matched, never exceeded.

Farrell reserves his highest praise for Kiernan, calling her “the most amazing woman I’ve ever coached at Princeton University for reasons well above and beyond being an athlete.” Kiernan embodies what Farrell aims to develop in his athletes. Sitting in his office, the coach counts out on his fingers an impressive list of her extra-curricular commitments. Brian Mondschein, the women’s assistant track coach, hopes that the program’s next head coach will encourage athletes to take advantage of all that Princeton has to offer outside of sports, especially in academics, as much as Farrell had. “You do what’s right for the sport, as well as for your kids. The people who compromise the academic experience for their athletes may beat you, but Peter does his best to provide both,” Mondschein said. “You can see how successful our alumni are. They’ve had a chance to be great students also.”

The women’s cross country team has repeatedly boasted the highest GPA among Princeton’s varsity athletics programs. When senior Emily de la Bruyère, Princeton’s No. 2 finisher throughout the 2015 cross country season, was faced with a tough choice between running cross country nationals or interviewing for the Rhodes scholarship, Mondschein said Farrell was adamant she go to the interview. Mondschein called this “doing the right thing,” and he said it characterized Farrell’s legacy. (De la Bruyère later received a 2016 Michel David-Weill scholarship to pursue a master’s degree in international security at Sciences Po in Paris.)

As much as Farrell has praised academic prowess on his team, Farrell has high regard for a certain competitive spirit in athletics. After a freshman year plagued by injuries and one particularly bad stress fracture, doctors told Kiernan that she should not run anymore; Farrell told me that her mom said, “You don’t know Reilly.” He is most proud of the person “who asks for nothing,” who puts her head down and does the work, and doesn’t expect anything in return, but succeeds nonetheless. “Ally, a race is like a painting — you sign it at the end,” Farrell told me, referring to Kiernan’s 2009 fifth place finish at the Heps. Kiernan is just one woman among several hundred who embodies the characteristics Farrell prizes most.

Driving the legacy Farrell will leave behind is a consistent coaching philosophy. Every year at the start of September, Farrell gave a beginning-of-the year speech to the cross country team. He says that the challenge of distance running is to get as close as possible to the edge without falling over it. For female distance runners, it is a hard lesson — it is the lesson— to learn. Kiernan called it “the balance between ambition and self-preservation.” In most sports, to get better you work harder. In distance running, all too many women work so hard that they break down. “There is something destructive about the most extreme levels of ambition in female distance runners,” Kiernan said, and Farrell has, as he puts it, “seen it all before.” Farrell gives this lesson once at the meeting, and then watches as women inevitably walk away from the doctor with unfavorable diagnoses. He won’t say it again until the next beginning-of-the-year meeting. Just like Van Cortlandt Park, Farrell checks in with his women at the mile, and then lets them figure it out the rest of the way.

Henderson told me that Farrell’s approach is intentional; he sees his role as a teacher whose job it is to help women learn to stand on their own two feet. By the time they leave the program, they should know what they need. Farrell parents the same way he coaches, Henderson said. Farrell likes to tell a story about his young kids asking him to buy them a hot dog at the pool. He refused. He told them, “Go buy it yourself.” Farrell knows the price of his philosophy, and Henderson tells me Farrell gets mad only when he watches an athlete making the same mistakes again and again, when he has to watch history repeat itself.

More than anything, “Farrell has a commitment to celebrating the living history of the program,” Kiernan told me. He tells stories of former athletes constantly, careful to never compare them to current athletes. When Lizzie Bird broke Ashley Higginson’s indoor mile freshman record two years ago, Farrell told Bird about the woman who held the record before her, someone he called “charmed, someone who good things happen to because they’re good people.” He texted Higginson, who missed out on a spot in the 2012 Olympics by finishing fourth in the 3,000-meter steeplechase, to let her know. “Farrell worked as a history teacher for years,” Henderson told me. “He’s not going to be inclined to ignore the past.”

When Kiernan sent a message to add to Farrell’s video send-off, she began, “Dear Coach Haggardy… Just kidding.” Kiernan explained that in her first email to Farrell, she accidentally addressed him as the then-Harvard coach. “Thank you for forgiving me that indiscretion, and also thank you for not letting me live it down in the ensuing decade since,” Kiernan joked. Kiernan went on to thank Farrell “for building the institution that is Princeton women’s track.” “Every time I put on the orange Princeton ‘P’ felt like a chance to try and do something great and to earn a spot in the lore of the institution and, at best, become a story that Peter might tell to a subsequent generation of Tigers. It’s hard to imagine the institution without you.”

In the compiled video that played at Farrell’s last track banquet, video messages from women in Farrell’s first recruiting class all the way to his last played on the screen. At no other moment had Princeton track and field been more evidently connected to one man. “Think of all the athletes whose central Princeton memories revolve around their teammates and this team,” Mondschein said. “That’s what Peter created. He created the environment in which people loved each other. And they’ll always have some funny story or Peter-ism to remember him by.” Farrell will be missed as a coach, as the man connecting generations of women together, but also as a friend. “It’s hard not to miss somebody you’ve been working with for 39 years, you know?” Samara said, sitting on a bench on the infield of the track, as rain began to fall.

“It’s my baby. I birthed it, I nurtured it through tough times and good times,” Farrell said of the program he guided for 39 years. Come next fall, the man tying all those women together will be gone, and the chance to become a story Farrell would tell later on will go with it. But the institution he built will live on.

And on the very trails where Farrell began running and finished coaching, Princeton women will continue to make history.