Bluetooth devices hidden in ball caps or headphones. Surreptitious hand signals. Consultation using gadgets like the Apple iWatch and Google Glass or with computers during bathroom breaks.

Major league sports and the Olympics aren’t the only arenas acting against cheaters. Competitive chess is, too — and Ken Regan ’81 is determined to ferret out the miscreants.

Cheating is increasing at some of the highest levels of chess: One player was convicted and three others were referred to the World Chess Federation’s ethics commission since its creation in 2013 (judgments from the commission have yet to be announced). One year later, the chess federation (FIDE) adopted new guidelines, which introduced metal detectors and security cameras at tournaments.

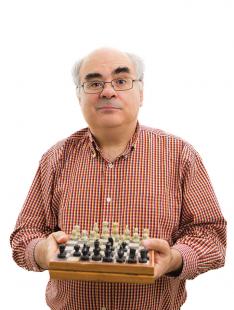

Regan has been helping to detect cheating since 2006, and his background makes him uniquely qualified: At 13, Regan became the youngest American since Bobby Fischer to hold the U.S. Chess Federation rank of master; he led the chess teams at Princeton and at Oxford, where he earned, respectively, a math degree and a Ph.D. in computational mathematics. According to Regan, an associate professor of computer science at the University at Buffalo, the number of possible cheating cases referred to him this year has “substantially increased.”

“Computers have gone from chump to champ since I began playing tournaments in 1970. ... Evidentially a few in my [playing] class have agreed, because they were caught consulting devices during their games. It’s a big problem,” he says in a 2014 TED Talk. “What about those not caught yet? That’s where I’ve been called in.”

Regan volunteered to help after the chess world was rocked by scandal. In 2006, Veselin Topalov, a finalist in the world championship, claimed his opponent, Vladimir Kramnik, was consulting a chess computer program during bathroom trips. At the time, there was no statistical method to identify computer assistance in chess; Kramnik won the tournament and was named World Chess Champion. (He was later proven innocent of cheating.) But the controversy, now known as “Toiletgate,” sparked unprecedented paranoia.

“It looked to me like the whole chess world was breaking apart,” Regan says in an interview.

For a week during October 2006, Regan stayed up until 1 a.m., alternating focus between his computer screen and the baseball playoffs on TV. Eventually he developed a computer model that assigns probabilities to moves according to a player’s skill level. Regan then examines matches that are flagged by the software to see if moves by a player with mid-to-lower skills are consistent with what a computer would do.

“You can’t just say, ‘You played too well.’ ... Anything apart from raw performance is a matter of cognitive style,” Regan said in the TED Talk. “Computers not only play better, they play different.”

READ MORE: Regan ’81 and former Princeton computer science professor Richard Lipton’s blog

Regan’s software monitors thousands of matches each week, compiling and analyzing moves of all available tournament games — in 2015, it recorded more than 31,000 player-performances (i.e., one player’s moves throughout a tournament, which is typically nine games) across almost 150,000 tournament games. Last year, a handful of indications of cheating were found — some are being looked into by FIDE, Regan says, but the organization has yet to determine a formal protocol for sanctioning cheaters. The players in these tournaments are considered to be some of the best in the world, Regan says, and his software helps tournament staff know whom to pay attention to based on potential cheating incidents in the past.

Finding cheating “is very wrenching,” he says. “It is an existential threat to chess and to the camaraderie that’s supposed to accompany chess.”