Princeton University does not tolerate sex or gender discrimination, including sexual misconduct such as sexual harassment and sexual assault, stalking, and intimate partner violence. These behaviors are harmful to the well-being of our community members, the learning/working environment, and collegial relationships among our students, faculty, and staff.

— Rights, Rules, Responsibilities, 2016

In trying to remain au courant here at History Central (oxymoron alert), the selection of potential topics is often more challenging than the actual telling of tales, given Princeton’s institutional history stretching rearward beyond even that of the country itself. Alums love to read about sports, the brave (or bizarre) road to Nobel prizes, midnight a cappella concerts in various arches, ceremonial occasions involving world leaders, great teachers, the globalization of education and culture, Olympic medals, and glorious structures arising magically like Brigadoon amid the vast New Jersey endowments. I know I do.

But alas, along the way in life I’ve come to realize that taking your cod liver oil may often be more productive than another bag of Skittles — if only because mom says so — and accordingly I’ve found the discipline of creating columns with historical insight on some relatively nasty topics to be meaningful, although I do get the feeling some readers just nod knowingly and disengage their attention until the next mention of Hobey Baker 1914 or Fred Fox 1939. In this somewhat Quixotic but purgative vein I’ve written about the unfamiliar history of African Americans integral to Princeton, the total inanity of bicker, the systemic and lengthy marginalization of Jews in admission and on campus, the shallowness of yelling “privilege” at one another, even the morality of institutional involvement in weapons and clandestine research.

But perhaps my most important lesson learned in this regard is what happens when I decide, for some reason or another, to consider some historic warts and/or group psychoses (at Princeton? Really?) and choose not to write them up. This leads to such as last year’s episode in which I discussed the substantial shortcomings of Woodrow Wilson 1879, while in addition pointing out my own shortcomings in not addressing it long before. Thus I ended up with both the toil of creating a substantial column, plus a sense of self-disappointment at my own tardiness and misreading of my fellow Princetonians, who clearly would have welcomed the message many years earlier. There is a moral here: If you see something, say something.

Which brings us squarely to sexual harassment.

You would suspect the historical record of a male-only institution of 223 years to be seriously testosterone-heavy prior to the 1969 admission of undergraduate women. Meanwhile, macho vestiges of the 19th century — the dominance of the Prospect Avenue clubs in its social life, the significant male athletics presence, and (let’s be honest) the highly involved alumni (many of whom always longed for the imaginary Fitzgeraldian atmosphere of their youth) — conspired to make Princeton a daunting challenge to an accomplished woman just trying to get an education. As far as the official power structure was concerned, the astonishing assertion from the head of campus security in 1973 that there “has never been a sexual assault on the campus” pretty much captures the institutional alertness of the time to physical safety in the Orange Bubble. This was proffered despite (just for example) the celebrated incident of a pregnant faculty wife who was verbally abused by club members while simply walking down Prospect in May 1969; the case bounced around campus headlines and discipline hearings for almost a year (the Inter-Club Council astoundingly refused to give the name of the perpetrator to the University) before being bizarrely settled with a student suspension, not for assault but for lying about it.

In such circumstances, the issue of sexual misconduct unsurprisingly became entwined in the women’s movement, despite — think about it — not really being a women’s issue as such. As women’s studies (which became an academic program in 1982 under acting director Nancy Weiss, later Malkiel) and women’s health services improved, and the ratio of women to men became greater, many people felt (or hoped) that periodic incidents of male oppression would become more isolated and unacceptable to the community. But two more assaults on the Street in 1981 led the 10-year-old Women’s Center to hold its first Take Back the Night march down the avenue. The discrimination suit against the all-male clubs by Sally Frank ’80 was already beginning to wend its way through the judicial system, and so the topics continued to be confused in the public mind. Town and University authorities rarely mentioned sexual attacks, and yet anonymous surveys of American college women at the time said as many as one-third were assaulted during their time in school.

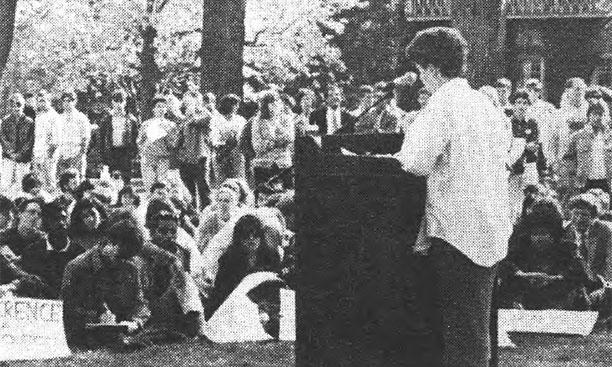

The focus on dealing with campus sexual assault for the next few years dealt principally with warning the potential victims: travel in pairs, that kind of thing, and once in a while a whiff of the old “don’t dress provocatively” blame-deflection attitude. A sexual-assault forum sponsored by the Women’s Center in December 1986 was canceled because of lack of interest. This malaise came to a dead stop (inevitably, in retrospect) just two months later, when a male student at Dial, unprovoked, addressed a junior woman student there as a “slut”; words were exchanged and, in the end, he was suspended for a semester while she received a dean’s warning letter for being “provocative,” which enraged a wide range of the student body. And so, before Houseparties 1987, there was a huge second Take Back the Night march with men as well as women, which stopped at sites of nine recent assaults on campus; when it then proceeded down Prospect, some male club members gathered and obscenely taunted the group. One of the drunken students involved was charged by the Borough of Princeton with lewdness, harassment, and disorderly conduct; he urged the authorities to regard it as a prank, not sexual harassment.

The University’s response included the creation of the Sexual Harassment/Assault Advising, Resources and Education (SHARE) office, which, along with eventual federal regulations on incident reporting and the insistence of the trustees, continues to make it abundantly clear to all students what the consequences are should they persist in threatening their peers. Section 1.3 of the Princeton community-standards manual Rights, Rules, Responsibilities deals with “Sex Discrimination and Sexual Misconduct.” It currently runs more than 10,000 words.

Sexual-assault information confronts every freshman coming to campus now; there is no way to avoid the topic baked into their orientation. An increasingly high proportion have already heard it in high school as well. And so, after all this sensitizing and soul-searching, where are we? Detailed surveys are done and publicized each year; the number of students who had one or more experiences of inappropriate sexual behavior was down to 15 percent in the 2016 Princeton “We Speak” report — still one in seven, still disturbing. And for novelty’s sake, we’re using the magic of social media to try to be provocative. Just for starters, we have members of a men’s swimming and diving team who are too mysoginist, uncaring, or self-centered to even keep themselves eligible to compete in a sport they love. They have been oblivious to the historical or simple caring issues of sexism, or to their own need to rise above it and become real, humane men. Perhaps even worse, many of them — and you know this is true without asking, because that’s how sexism works — knew this was wrong, knew this was beneath them, knew they should speak up … and didn’t.

If you see something, say something.