A player defined and controlled non-contact team sport played with a flying disc on a playing surface with end zones in which all actions are governed by the 'Spirit of the Game™’.

— “Official” Definition of Ultimate

It behooves a savvy columnist (should you run across one, please alert me ...) not to reveal any of the fundamental tricks of the trade here in virtual reality, or the virtual Orange Bubble, or wherever it is we are. Take the Sweet Spot, which I’m sure every columnist would like to pretend doesn’t exist, but hey, we know better. On occasion, when people are yelling at you, or your gray matter isn’t quite up to speed, there’s The Guaranteed Topic you can fall back on to provide a few hundred rosy words, which will be embraced as warm and evocative by all who wander by, be safely beyond criticism or controversy, and elicit flowery images of Grantland Rice, Walt Whitman, and other Venerable Bards of ancient renown. In this space, the Sweet Spot – or the one I’ll admit to – is the storied tradition of Princeton’s great athletes, knights in shining white uniforms with generous orange and black accents, who venture onto the holy field of battle with pure heart and noble demeanor to Dream the Impossible Dream and Right the Unrightable Wrong. Mention Hobey Baker 1914, Bill Bradley ’65, Mollie Marcoux ’91, or Pepper ’36 and Betty Constable, and you’re the finest scribe in history. Conversely, talk about the ergonomics of the C Floor renovation at Firestone or the First Amendment implications of the East Asian studies department in World War II, and you can feel the apathy welling up in virtual Tigerland, thick enough to erode the scenic coastline of paw.princeton.edu.

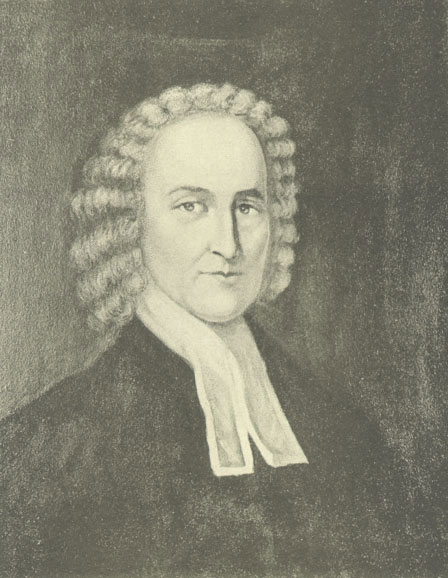

But in my ear is still the insistent voice of President Jonathan Edwards (remember “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God”?) plus dozens of other strait-laced Presbyterians sternly demanding I come clean, and admit that the Jumbotron at Princeton Stadium, however uplifting, is not exactly what they had in mind when nursing the College through the Revolution, the Civil War, and a few dozen other crises of varying severity. They were far more concerned with generating moral, humble, and upstanding graduates than recreating the Circus Maximus. And they were probably on the right track. So with all deference to the great varsity athletes and records we all love to discuss, today we’ll talk about the real and important world of club athletes, whose experience much more closely corresponds to the hard work and life lessons embodied in the Service of All Nations than even a national ranking and 31-game winning streak. And then, after everyone ignores the effort, we’ll go back to normal, discussing flashy NCAA championships, Nobel Prizes, and U.S. News rankings.

If you wanted to be assertive about it, the first football games ever – the fabled Princeton/Rutgers matches of 1869 – were more akin to rugby than modern football. But the modest (if well-lubricated) ruggers of today only claim a pedigree back to 1876, when Columbia, Harvard, Princeton, and Yale agreed – for a time – to use rugby rules for their football games. That, of course, quickly devolved into today’s billion-dollar business, while rugby itself took a hiatus, then was resuscitated on the Princeton campus as an independent sport in 1930. The ruggers, true to their club-team ethos, have ebbed and flowed over the years. But their current incarnation with a full (and highly successful) women’s side since 1979, dedicated Rickerson Field and spiffy Haaga House facility across Lake Carnegie, and more formally organized Ivy round-robin play, are a great example of what clubs can be with some alumni backing and focused participants, while still eschewing recruiting and the NCAA. The women (23 of them) have a larger roster than the men (18), and both teams are regularly in the hunt for the “Club Sport of the Year” awards given out by the athletics department. And to top it off, the women this year, with one lone senior on the side, swept to the Ivy Championship and third place in the national sevens tournament. Although coached – the women by Chris Ryan, the men by Richard Lopacki – the players are, by definition, walk-ons, and either the enjoyment is there or the bodies aren’t. That’s the simplest way to look at all the various clubs, and probably the most honest.

That certainly applies to the recent reincarnation of polo after its first run from 1903 to 1942, as noted so entertainingly by David Walter ’11 here. To say the challenges of putting together a functioning polo operation (hot chukker, baby!) within a mile of Route 1 are daunting is to say that Bernie Sanders will have a challenge trying to beat Hillary Clinton next year. Yet, here they are.

There are two broad categories encompassing the 37 current club teams at Princeton. The first comprises those folks who can’t qualify for and/or don’t like the strenuousness of the varsity programs in mainstream American pastimes like basketball, soccer, field hockey, ice hockey, lacrosse, and volleyball. Some of those club squads have complex schedules; some have a series of regional development meets – the club swimming program, for example, has a few multi-college meets through the year and even national championships in an impressive 30 events, but you can train with the team without competing in any of them.

In contrast, there are the sports that only exist on campus at the club level, and there we’re talkin’ let a hundred flowers bloom. This wide tent includes everything from the rugby teams to the 90-year-old sailing program to ballroom dancing, climbing, skiing and snowboarding, cricket, and – my personal favorite since I had zero idea what it was – kendo, for those Tigers whose self-fulfillment cannot be halted short of Japanese swordsmanship.

And then there’s the Ethos of the ’60s incarnate: Ultimate Frisbee. In homage to that other momentous New Jersey historic event, Rutgers and Princeton met in 1972 on the 103rd anniversary of the first football game in New Brunswick to initiate intercollegiate Frisbee. To this day a simple game, it can be highly skilled at its elite levels, and the Princeton men (“Clockwork,” of course) and women (“Clockwork Orange”) have had a number of successful squads over the years; the women this year made it to the national tournament for the first time since 1999. The most impressive thing about the sport, however, is its abiding faith in its players. There are no officials at any level; unique among team sports, everyone is on his or her honor to make boundary and reception calls, to count down the person in possession, and to obey “The Spirit of the Game”: According to its federation, “Ultimate stresses sportsmanship and fair play. Competitive play is encouraged, but never at the expense of respect between players, adherence to the rules, and the basic joy of play.” You can feel Jerry Garcia smiling down from above.

If I were an undergrad again, I’d go the next step and start a club Frisbee golf team. Home matches with the exciting 18th hole of Oval with Points could be contrasted to road events, such as trying to clock Columbia’s Alma Mater right in her, uh, laurel wreath. All the camaraderie of Ultimate, plus the freedom to munch pizza between shots.

Speaking of which, you might find it interesting to hear how this column came about. The New York Times is beginning a series on its very first historical citation of various terms, ideas, and names, and the debut of the term “Frisbee” in the Times was about the Princeton campus on Reunions Thursday, 1957. A follow-up op-ed piece by Gay Talese acerbically noted that “sane people can’t stand most toy fads for more than five months.” The spectacular degree to which he was wrong (there are something like 800,000 Ultimate players today), the frivolity of the feature itself (who really needs to know when the Times noticed, say, Tiny Tim?), and the attachment of the Frisbee counterculture to Princeton and, even more lightheartedly, to Reunions was just too good to ignore. And on Reunions weekend 2015, it probably reflects an appropriate context for club sports, extracurricular pursuits, and college friendships generally. The NCAA finals on ESPN are all well and good and flashy, but the final three holes on the Frisbee golf course (and a pepperoni slice) are forever.

Thus endeth the Lesson; maybe Jonathan Edwards will leave me alone now.

No responses yet