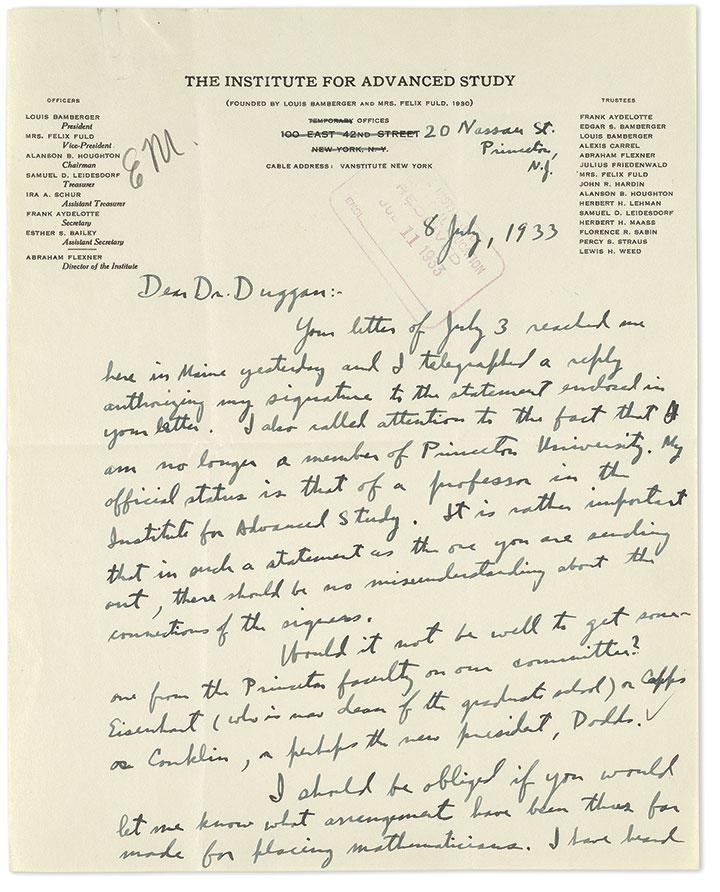

THE DATE WAS JULY 8, 1933. Oswald Veblen, a mathematician who had recently moved from the University to the newly minted Institute for Advanced Study, wrote a letter, addressed from his office at 20 Nassau St., to Stephen Duggan in New York City. The reason for his writing was an emergency in the world of scholarship. Three months earlier, on April 7, the Nazi regime in Germany had issued a decree that purged from the civil service all non-Aryans and “politically suspect” individuals. Because the civil service included universities, thousands of university researchers suddenly found themselves out of a job. Onlookers understood this, moreover, to be a sign of worsening conditions to come: “It is impossible to describe the utter despair of all classes of Jews in Germany,” Harvard law professor Felix Frankfurter — later a Supreme Court justice — wrote to a colleague soon afterward.

In response to this crisis, Veblen had begun writing letters to colleagues around the United States to encourage them to find places for “dispossessed Jews” in their own universities. The letter he sent July 8 contained the names of 27 scholars who had lost their livelihoods, along with their locations and their specialty fields; the recipient, Duggan, was the president of the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced German (later Foreign) Scholars, a new organization that aimed to help scholars in Nazi-occupied countries find work and safety elsewhere. Within a few days, Veblen sent several more lists, early envoys in an epistolary campaign that was staggering in its scope and accomplishments. For more than a decade afterward, Veblen held the center of a republic of letters that was dedicated to helping to bring refugee scholars to the United States — working against Depression-era budget deficits, a bureaucratic immigration system, and the threat of nativist sentiment at home.

The number of refugees saved by this rescue program is uncertain. The records of the Emergency Committee, which was only one of several foundations that helped refugee scholars, document 335 scholars who came to the United States, together with spouses and children, with the committee’s aid. In a time of public debate about refugees and the public good, the story of Veblen’s undertaking, which ultimately had a dramatic effect on American mathematics, is worth retelling. “If our story has a hero, it was certainly Veblen,” mathematician Lipman Bers said in 1988. “But there was also a collective hero: this generation of American mathematicians who, at the very beginning of their careers, experienced the influx of Europeans and who reacted to this influx with so much grace and so much cordiality.”

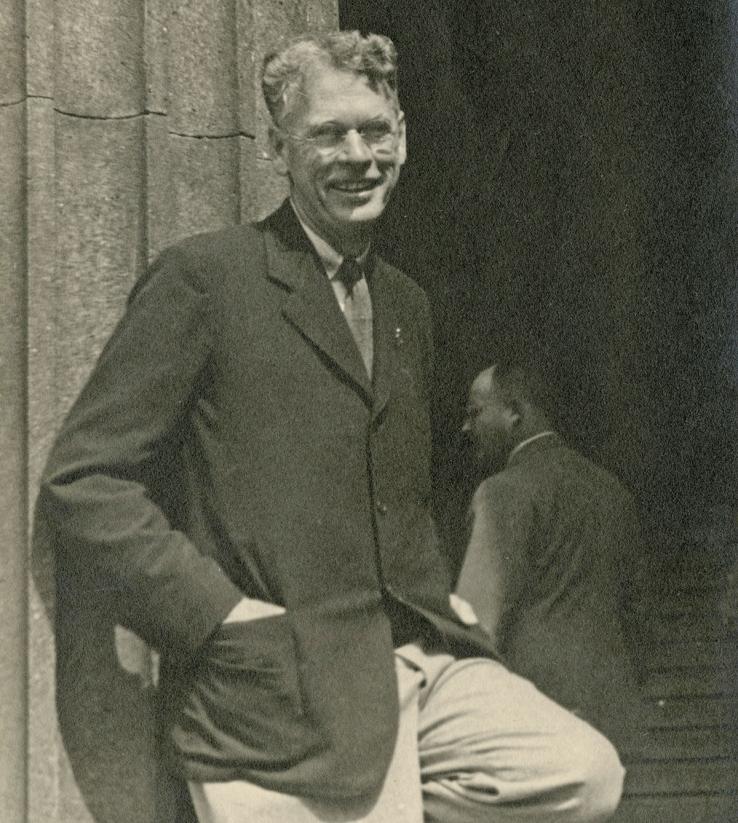

Veblen was born in Iowa. He came to Princeton in 1905, the recipient of one bachelor’s degree from the University of Iowa and a second one from Harvard and a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. Tall and lanky, he had the furtive vanity typical of a mathematician, dressing in handsome but deliberately shabby suits. One of his colleagues, Hermann Goldstine, recalled, “We always had a theory with Veblen that after he bought a new jacket and pants he would hire somebody to wear them for a few years so that they wouldn’t look new when he put them on.”

Veblen was forever thinking about ways to tend productive research communities. Famously, he started the tradition of the afternoon tea attended by members of Princeton’s math and physics departments, which continues to this day. Veblen also worked his way into a supervisory role in the design of Fine Hall, which he used to ensure that the building held common areas in which researchers could meet and converse.

Soon Veblen acquired a reputation at Princeton as a man with a good administrative touch. In 1930, the Institute’s founder, Abraham Flexner, recruited Veblen as the first faculty member in the School of Mathematics and the Institute’s chief recruiter. Veblen quickly proved his value by arranging for Princeton University to lend office space to the Institute’s faculty until it acquired its own buildings (thus ensuring that the Institute would be located in Princeton) and by enticing onto the Institute’s faculty established and rising luminaries like Albert Einstein, John von Neumann, Eugene Wigner, and Hermann Weyl, which gave the Institute immediate global recognition.

Veblen was able to build exciting communities in part because he had an eye for talent and an utter lack of professional jealousy. Goldstine later recalled, “I think the nicest part about Veblen is that however great a mathematician he was, and he certainly was a great mathematician, he recognized greatness in mathematicians and in scientists, and as far as I know he had no envy for people who were greater than he. And that’s not trivial.” Veblen placed his trust in von Neumann, a father of modern computing, for example, even when he didn’t follow von Neumann’s vision; at one gathering, Veblen’s wife, Elizabeth, said, “Oswald, you never did want that computer at the Institute, did you? You just thought that if Johnny wanted it, he should have it.” In the moment, her remark would have been embarrassing for von Neumann because it acknowledged that many great mathematicians thought digital computing was a waste of time. Years later, as the potential of computing became clearer, the anecdote would have been embarrassing for Veblen. But the lesson is that Veblen recognized von Neumann’s talent and trusted him to do good work.

The fortune of the Institute in attracting such great scholars did not happen in a vacuum. Von Neumann left his position at the University of Hamburg in 1930 to accept a position at Princeton University because he feared what the growing strength of Nazism might bring to Germany. Weyl, whose wife was Jewish, also recognized the worsening conditions, but he wavered on whether to leave his home country until almost the last possible moment. He fled to Princeton in 1933 with his wife and children. Einstein had turned down Veblen’s initial offer of a place in Princeton, but he realized in late 1932 that he would not be safe in Germany. As he and his wife left their country home in Germany before voyaging to the United States, he told her, “Take a very good look at it. You will never see it again.”

When the Nazi regime began its civil-service purge April 7, 1933, Veblen started writing letters to his American contacts right away — passing along news about displaced scholars and suggesting with diplomatic sensitivity that their departments might help to shelter colleagues from the rising storms in Europe. In late April, he wrote to a colleague at the University of California, Berkeley, “May I suggest that the situation in Germany opens up new possibilities for a solution of the problem of your Mathematics Department.” He appended a list of displaced scholars, along with knowledgeable praise for each. He wrote to Flexner, “I can’t help returning to the point that if the funds could be made available to spend, now would be a golden opportunity for starting some of the other departments” — referring to the fact that the Institute had only hired a mathematics faculty so far. He added, tactfully, “But this idea is so obvious that you have doubtless already considered it from all points of view.”

In late May, New York City’s Institute of International Education, with the help of the Rockefeller Foundation, created the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced German Scholars. The major activities of the committee were supplying information on available scholars to universities that expressed interest and, in many cases, supplying part of the salary if a refugee was hired, because immigration laws prohibited refugees from immigrating to the United States unless they had an offer for a job with an income above a certain threshold. Veblen joined the committee’s executive board during its founding year, and at his encouragement, Flexner joined in 1938. By 1941, the board also included Harold Willis Dodds *1914, the president of Princeton University.

To its credit, Princeton was the first university to reach out to the Emergency Committee with an offer of places for refugees. Luther P. Eisenhart, the chairman of Princeton’s math department, wrote to Duggan with news of possible openings for refugee scholars in the fields of art and archaeology, biology, chemistry, economics, experimental physics, mathematics, modern languages, politics, and theoretical physics.

Ultimately, the committee supported 15 who worked at the Institute or the University, including the mathematicians Richard Brauer, Kurt Gödel, and Carl Siegel; the economist Otto Nathan; the archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld; the art historian Paul Frankl; and the author Thomas Mann. But Princeton helped many more displaced scholars than this number suggests. Some European scholars who settled in Princeton fled Europe when they saw the writing on the wall but did not count themselves as refugees. Some scholars came with support from foundations other than the committee or without external financial support. When the Polish physicist Leopold Infeld ran out of money to work at the Institute, Einstein co-authored a popular book on science with him, which became a bestseller and kept Infeld and his family solvent. The great mathematician Emmy Noether, who taught at both Bryn Mawr and the Institute, had several agents in Fine Hall looking out for her welfare, including Veblen and mathematics professor Solomon Lefschetz, who suggested to Veblen that if she had trouble finding teaching positions, she deserved to have a permanent fund to support her work. Today, Princeton has an Emmy Noether mentoring circle in her honor.

The refugees who came to Princeton shaped the culture of Fine Hall, in particular, during a period that is now recognized as a golden age for mathematics on campus. The building became a refuge for people who, as exiles and newcomers to the United States, brought to the corridors and common rooms accents and manners from all over Europe. “In Fine Hall,” Infeld reported, “English is spoken with so many different accents that the resultant mixture is termed ‘Fine Hall English.’”

Today, archives from Boston to New York to Washington hold hundreds of files and boxes of Veblen’s letters that testify to his dogged work in response to the refugee crisis. His assistant, Wallace Givens *36, later said that Veblen tackled his correspondence first thing upon coming into his office in the morning. Veblen wrote to colleagues who had recently immigrated, asking for information from their overseas contacts. (“It would be a good idea to write me whatever you know in detail about the mathematicians and physicists who are in difficulties. What we lack here most of all is authentic news ... .”) He wrote to foreign diplomats asking for help for colleagues who had trouble with exit visas or who had been dismissed. He wrote to colleagues in fields outside of mathematics asking for comments on the work of scholars in those fields, so that he could give more detailed descriptions to potential American employers. He wrote to the committee’s secretary, Edward R. Murrow (later a famous journalist), to ask for updates on pending cases. He wrote letters of recommendation, he wrote to colleagues asking whether they had gaps in their departmental coverage, and he wrote to the committee and other aid groups to pass along affirmative replies.

Veblen and others at the Institute also negotiated on behalf of refugees with foreign governments and helped them navigate the massive amount of paperwork and permissions that the U.S. government demanded. Many would-be refugees struggled fruitlessly against this blockade of bureaucracy. One was the logician Kurt Grelling, a German Jew who worked in Belgium. When Germany invaded Belgium in 1940, Grelling was deported to an internment camp in France. His wife, a Gentile who refused to leave her husband, went with him. Grelling managed to stay in touch with colleagues in the United States, including the refugees Paul Oppenheim and Carl Gustav Hempel, who found him a position at The New School in New York City. But the work of securing an offer and a visa was excruciatingly slow, taking more than two years from the time that Grelling started seeking one while in Belgium. In 1942, Grelling and his wife died in Auschwitz.

Veblen’s personal archives, along with the testimony of Fine Hall denizens, show that he extended tremendous personal support to U.S.-born mathematicians as well. The American mathematicians James Alexander 1910 *1915, Alonzo Church ’24 *27, Alfred Foster *31, Wallace Givens, and Robert Walker *34 all benefited from Veblen’s having “adopted” them (in Foster’s term) early in their careers. Robert Carmichael, who lacked a bachelor’s degree when he had a paper published in a prestigious journal, accepted an invitation to Princeton from Veblen “and was launched on a mathematical career,” said Princeton professor Albert Tucker *32. During the height of the Depression, when jobs in mathematics were hard to come by, Leo Zippin stayed at the Institute for some five years, according to Institute fellow Leon Cohen, “because there wasn’t a suitable position for him. My impression was that young mathematicians of some talent were regarded as resources to be saved.” Cohen added, “I hesitate to attribute views to Veblen, but the considerations that seem to have actuated him were two: a concern for the welfare of mathematics itself, and a humane concern for certain individuals who had talent.”

His letters serve as a reminder that mighty changes sometimes come down to the work of small groups and individuals. Cohen did some very humble work to great effect one day in 1933 when, as a professor at the University of Kentucky, he received one of Veblen’s lists of displaced scholars. His department decided to bring in someone from the list but had no funds available, so Cohen and a colleague walked up and down Main Street and raised money from every merchant they could — enough to cover a good part of the salary. Richard Brauer, the refugee who joined their department, went on to win the National Medal of Science. Similar lists went out steadily from Veblen’s office to institutions all over the United States, urgent in their volume but, in their expression, as mild and as persistent as snow: “If it were thought advisable ... ,” “It is my impression ... ,” “The clerical work would be very little, using the available facilities.” In 1939, when it appeared that larger universities had taken in all the refugees they could, Veblen wrote to Duggan to ask delicately whether he thought the committee might be persuaded to fund someone to travel around the country to investigate possible openings at smaller colleges.

“I think all of Veblen’s life he was a natural administrator and leader,” Goldstine said. “He was the kind of guy who would keep dripping water on the stone until finally it eroded. If it didn’t happen otherwise, he just kept at it, and at it, and at it.”

Nonetheless, there was more to do than could possibly be done. The committee’s first annual report, published in January 1934, reported that its workload was urgent: “Not less than 50 letters dealing with the problems of dismissed professors are received daily and as many answers are dispatched. Interviews with 12 to 15 persons are daily occurrences. Telephone interviews keep pace. The dossiers containing correspondence, curricula vitae and lists of publications of some 1,100 individual scholars are filed in our office.”

Read today, many of the letters in the archives are incredibly sad. One man, for example, sent a letter to the committee in October 1934, appealing for his colleague Professor Otto Blumenthal. (“Dr. Blumenthal was for many years professor of mathematics at the University of Aachen. In the upheaval of a year ago, he was put out of his position; and since then he has been without occupation. Besides making important contributions to the theory of functions, he has put the whole mathematical world in his debt by his long continued service as editor of Mathematische Annalen. He would very much like to find a field of activity in an American institution.”) The writer says that he went to Veblen for help, and that Veblen advised him to make sure Blumenthal’s information was on the committee’s list of scholars in peril. The committee was not able to find a place for Blumenthal. He perished in 1944 in the Theresienstadt concentration camp.

After the United States entered the war in December 1941, researchers at universities across the country worked with the Office of Scientific Research and Development to apply their expertise to wartime problems. Refugee scholars and the students they trained contributed invaluably to this effort, applying their expertise to applications such as psychological warfare, wartime economics, the plotting of shipping routes, the calculation of the likely flight paths of airplanes, and the development of tactics for fighting gun battles at long distances. Veblen, who had served as an administrator at the Aberdeen Proving Ground military facility during the First World War, helped to connect mathematicians to wartime projects, as did von Neumann, who served as a consultant at Aberdeen in the 1930s and 1940s. Valentine Bargmann, a refugee who joined the Institute and then became a professor in Princeton’s math department, worked with von Neumann on gas dynamics, which Bargmann later said was “certainly used in connection with building the atom bomb.” Goldstine, another von Neumann protégé, took a position at Aberdeen where he worked with von Neumann as a developer of the ENIAC, the first modern digital computer.

The ethnic and political purge of German universities marked the end of Germany’s reign as the global capital of the sciences — and the corresponding rise of America’s scientific reputation. Germany’s proportion of Nobel Prize winners plummeted; at the same time, America’s share skyrocketed, with immigrants comprising a growing portion of its 20th-century laureates. (In 2016, all six Nobel Prize winners from the United States were foreign-born.) As the Princeton historian Michael Gordin writes, between 1880 and the 1930s, a large share of scientific books and journals were written in German: “During that era a scientist would have had excellent grounds to conclude that German was well poised to dominate scientific conversation.” Starting in the 1930s, however, Germany declined as a language of science and has never recovered. This is not merely due to the flight of scientists or the horrible reputation Germany acquired during these years, Gordin says; it is also due to “the rupture of the graduate-student and postdoctoral exchange networks.” Foreign students stopped studying at German universities, previously a most desirable destination.

“I heard of a scientist, the best in his specialized field,” said Infeld, “who had two appointments: He spent half the academic year in Germany and half in America. When Hitler came to power the professor resigned from his position in Germany. He finished his letter of resignation ironically by expressing the hope that the German minister of education might succeed in raising the level of German universities during his whole future life as much as he had raised the level of American universities during the first three months of his term of office.”

A similar story tells how, in 1934, the new Nazi minister of education visited Göttingen University, long famous as the world leader in mathematics, and asked the mathematician David Hilbert, “How is mathematics in Göttingen, now that it has been freed of the Jewish influence?”

Hilbert replied, “Mathematics in Göttingen? There is really none anymore.”

In 1941, Infeld gave Göttingen its briefest eulogy: “Now Göttingen is dead; it took a hundred years to build it and one brutal year to destroy it.”

Elyse Graham ’07 is writing a book on the wartime flight of mathematicians from Europe.